I have always been fascinated by the story of the kibbutz movement in Israel. From their beginnings in the early part of the twentieth century, the kibbutz as a form of communal enterprise and living has been held in high esteem by many naive Westerners.

I take my hat off to the kibbutz movement for their marketing success in creating an image of an idyllic arrangement that was often brutal and heartless. Talking about heartless, the way in which children were raised on a kibbutz is surely the standout example.

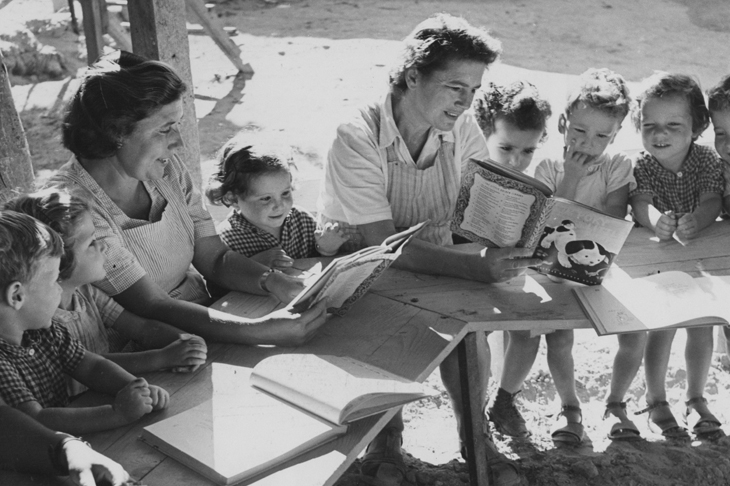

Instead of parents being actively involved in the rearing of their offspring, children were placed in separate dormitories with some members of the kibbutz were assigned to their care. The parents might spend short periods of any day with their children, but essentially their care and nurture were forcibly subcontracted to others.

Unsurprisingly, many parents, particularly mothers (can I say that?), were unhappy with this arrangement. It was one of the factors that contributed to their recent transformation. Parents now live with their children in separate units and care for them in more traditional ways.

I was reminded of this by all the hysterical talk about the role that taxpayer-funded childcare should play in Australia and how we need even more taxpayer dollars thrown at the sector so women can work or work more hours per week, even when their children are very young.

Now let me run through some basics. The federal government currently shells out around $10.3 billion per year to subsidise childcare fees. Twenty years ago, it was less than $500 million. The subsidies are extremely generous, with families on combined incomes up to $353,000 per year eligible for up to $10,560 per child per year.

In theory, there are activity tests attached to the receipt of the subsidies but you can drive a truck through them. Do a course, look for a job, volunteer a bit – all this counts, as well as having a fair dinkum job.

But here’s an important part of the deal – you get twice the number of subsidised hours as your activity takes up. So if you have a 16 hour per week job, you get 32 hours of subsidised childcare. Plenty of time to get your nails done, have a hit of tennis or whatever.

The government has announced an additional $1.7 billion in childcare spending as part of the Budget to apply over three years and commencing in July 2022. This will involve the removal of the annual cap, which is the bane of the existence of the wealthiest families, and more subsidies for families with two or more children in childcare.

But here’s the biggest con of all: the proposition is that all this spending will lead to more women entering the workforce and more women working more hours. Evidently, there are just too many women who want to balance family and work responsibilities. Rather they need to be incentivised to dump their children in childcare centres for longer each week.

In turn, this is premised on a presumed response of women to these new incentives – what economists call the supply elasticities. The research of the Productivity Commission clearly shows that these responses, certainly at the margin, are very weak.

In other words, spend a whole lot of taxpayer money on subsidising childcare and the parents (and childcare centres) take the money but not much changes in respect of workforce participation. Again to use economist-speak, there are distributional transfers but tiny efficiency gains.

This is completely consistent with longer-term trends in women’s workforce participation in Australia. The biggest gains in the participation rate occurred between 1980 and the early 1990s when there was negligible taxpayer support for childcare.

To be sure, there have been further gains, but nowhere near proportionate to the rising rate of government spending on childcare. Moreover, older women aged over 60 years have seen the highest growth in participation recently, not women of child-bearing age.

There is also the issue of where the jobs and additional hours would come from should women decide to up their workforce participation. Would other labour market entrants and other workers, particularly young ones, lose out? (This is the cross-elasticity issue, to be technical again.)

None of these real-life issues matter to the noisy, public urgers for more taxpayer spending on childcare. The Business Council of Australia thinks it’s on a winner by campaigning on the topic and the elite Chief Executive Women Australia is also on the case.

Underpinning her frightening ignorance of the topic, current president of CEW (and former adviser to Paul Keating), Sam Mostyn, has declared in writing that ‘there is an opportunity to consider childcare investment as a big, bold investment to empower Australia’s entire talent pool now and in the future’.

She even cites a highly dubious KPMG study that ‘shows increasing women’s workforce participation by just 5 per cent would boost Australia’s real GDP by $20 billion over five years’. It’s not clear whether she means 5 percentage points or 5 per cent (does she know the difference?) but the reality is that, either way, this is a huge change – it’s not ‘just’. And $20 billion is a small number given that annual GDP is now close to $2 trillion.

The childcare mafia knows that the workforce argument is not enough and quickly moves onto the supposed benefits of early childhood learning that childcare confers on our little ones. Here again the evidence is extraordinarily weak, save for children from very disadvantaged family situations. But disadvantaged children are significantly underrepresented in subsidised childcare, with the majority of the attendees from middle-class families.

There is also a deliberate conflation made between long day care and pre-school for three- and four-year-olds, the benefits of which are reasonably convincing. Childcare champions also attempt to hide the fact that young children are much more likely to get sick in childcare than if they are at home.

Tossing more taxpayer money at childcare may buy some votes and it most certainly will be welcomed by the owners of childcare centres whose incentives are simply to raise fees to eat up the additional subsidies.

Let’s eliminate all those faux arguments about it being good for the economy after the costs are taken into account. You see money doesn’t actually grow on trees.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in