Everyone knows Helen of Troy. The feckless sex popsicle betrayed her husband, Menelaus, and ran off with the dashing Paris, which triggered the ten-year Trojan war. The Greeks were victorious but after sacking the city they went straight home again. So what was the point?

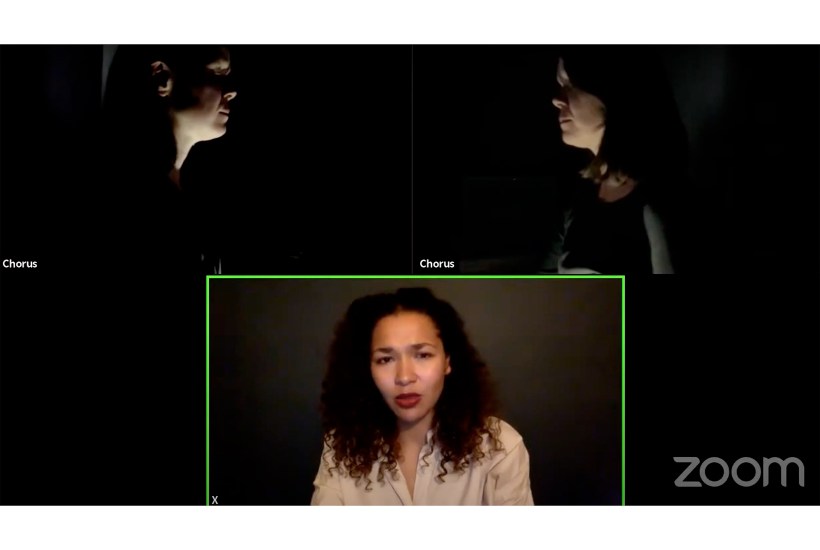

Euripides’s play Helen takes a radically different approach in this Zoom production by the Centre for Hellenic Studies at Harvard. The script is crammed with enough twists and turns to make an entire Net-flix series but the running time is barely 60 minutes. Euripides opens with a narrative bombshell by revealing that Helen was absent from Troy throughout the conflict. The gods had spirited her to Egypt where she enjoyed the protection of a local warlord who declined to seduce her. This courteous gent has died and Helen is now being targeted by the powerful and lusty Theoclymenus. She claims sanctuary at a temple and refuses to marry him while Menelaus is still alive.

Thus Euripides overturns the traditional portrait of Helen as a sex-mad, bed-hopping airhead. Here she’s a pious, chaste and intelligent operator. Menelaus arrives in Egypt and the pair are reunited. But there’s a problem. During the war, Menelaus recaptured ‘Helen’ from Troy and hid her in a cave. What’s going on? Euripides explains that this ‘Helen’ was a figment created by the gods ‘from a cloud’. In other words the entire war was caused by a mirage.

The lovers know that they’re in mortal danger. Theoclymenus hates all Greeks and will kill Menelaus if he gets the chance. So Helen hatches a plot. She tricks Theoclymenus by telling him that Menelaus’s corpse has been discovered on the shore. She offers to accept his proposal as soon as her late husband has been buried at sea. Theoclymenus falls for it and provides her with a 50-oared boat in which she plans to escape. At the last minute he nearly scuppers the plan by deciding to attend the funeral himself. Helen thinks fast. ‘Do not serve your slaves, O lord,’ she says. The funeral leads to a surprisingly upbeat ending with no stabbings, gougings, murders or suicides. It’s a welcome change from the usual high-decibel bloodbath at the end of a Greek tragedy.

This is a fantastic show to watch. The cast, mainly British, are excellent. Even better are the panel of American academics who discuss the production afterwards. They seem convinced that Euripides was writing about present-day America, and they tie themselves in knots trying to find evidence of racial and sexual exploitation in the story. One of them suggests that Helen is a black female who suffers from both ‘hypervisibility and invisibility’. That sounds like a contradiction but it passes unchallenged. This is how it works. If you mention ‘suffering’ in a debate, your opinion becomes an immutable truth.

Rebecca Buckle has turned her chronic health problems into a lecture about women and disease. In a bygone age, she tells us, she’d have been labelled a ‘hysteric’ and confined to an institution. The incurable ailments from which she suffers include fatigue, insomnia, bad joints, chronic pain and brain fog. ‘I’m generally a bit dizzy all the time,’ she says. ‘I’m allergic to anything and nothing.’ She has episodic respiratory problems. ‘I can breathe out but I can’t breathe in.’ And because she’s unable to produce collagen her finger joints are apt to become dislocated. She’s been asked more than once by doctors to demonstrate this trick in the examination room.

It’s clear that numerous health professionals, all of them male, have let her down badly. When she was a student she was told to cure her insomnia with gin. She once asked a doctor if he thought she suffered from fibromyalgia. ‘I don’t believe in that,’ he said, ‘so there’s nothing I can do for you.’ Understandably, she’s keen to pour scorn on ancient experts who misunderstood female anatomy. ‘Galen thought the uterus was an inverted scrotum trapped within the body.’ In the 19th century, the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot became famous for diagnosing upper-class women with hysteria. Buckle makes the point that popular images of swooning ladies were copied by actresses and became part of the repertoire of gestures used in the theatre.

This is a very odd show. Partly confessional and partly accusatory. Some of her claims seem questionable. Is it true that ‘women are ten times more likely to die of a heart attack because their symptoms aren’t taken seriously’? And very few classicists will agree that ‘the central idea of Greco-Roman history was the wandering womb’.

Buckle admits that no woman has been diagnosed with ‘hysteria’ since the 1950s, and this leaves her rather short of female woes to complain about. So she laughs at Galen instead. Fair enough. Whatever makes you happy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in