Michel Barnier – still officially the EU’s Brexit taskforce leader – gives few interviews. As a Savoyard and keen mountaineer, as he habitually reminds us, he is a cautious man who advances step by step with the long climb firmly in his sights. So it was something of a surprise to see him appear on 16 February before the French Senate Brexit follow-on committee (renamed ‘groupe de suivi de la nouvelle relation euro-britannique’). It is a sign of the importance of how Brexit will play out for the French that the Senate has formed a very senior 20-strong commission to monitor and react to Brexit implementation and next stage negotiations.

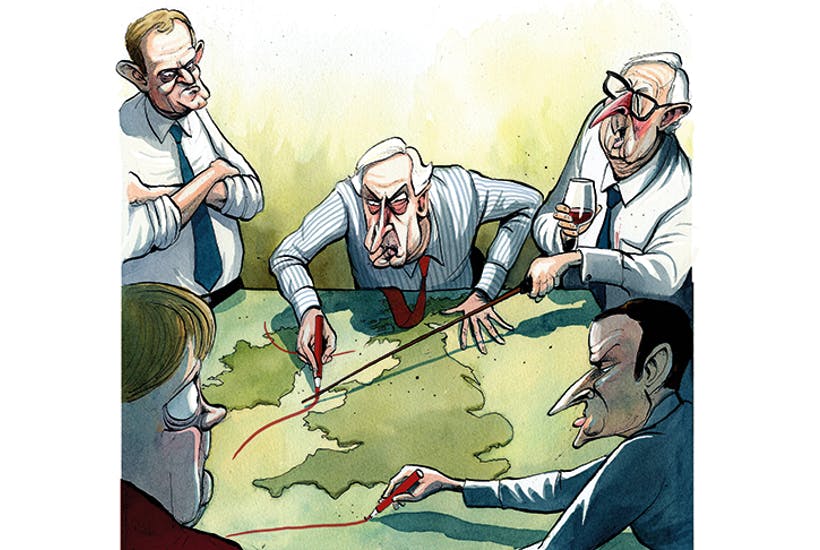

Of course Barnier and France have an interest in Brexit being implemented as they see fit. But is there more to their common purpose? For Michel Barnier, former Gaullist agriculture and foreign minister, former president of the Senate Foreign Affairs Commission, is said to be preparing his candidacy for the May 2022 French presidential elections.

The traditional Gaullist French right, Les Républicains, has no consensual candidate and is in even greater turmoil following Nicolas Sarkozy’s shock prison sentence for corruption. Barnier’s outsider and clean pair of hands status gives him a fighting chance. He is nationally feted for having done a good job on Brexit. His stolid, humourless, image is given spice by what some see as a desire for revenge on Emmanuel Macron, who preferred Ursula von der Leyen to Barnier for president of the European Commission. At 71 in 2022, Barnier would still be a tad younger candidate than François Mitterrand in 1988.

The combination of a semi-liberated Barnier, and a distinctly pessimistic French Senate, produced clear indication of EU and French fears about a post-Brexit world.

The session opened with a question to Barnier from the chair of the Senate Commission as to Britain’s frame of mind given their sensitivity over Northern Ireland and their attitude over vaccines. Would relations with London be constructive or ‘combative’, ‘perhaps even revanchard?’

The French it transpires are seriously concerned that on foreign policy, security and defence their cherished partnership with the UK, based on the 2010 Lancaster House agreements, could be undermined if EU-UK relations deteriorate. Barnier worsened the picture stating that the UK insisted on excluding defence and security from any Brexit agreement, much to the EU’s disappointment.

Although absent from British media, French senators were worried about the impact Brexit border checks were having on French exporting companies and how overzealous controls on UK shell-fish exports might provoke retaliation when Britain ends its grace period.

But in Jekyll and Hyde mode both Barnier and the Senate were insistent that the Withdrawal Agreement and the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) must be applied fastidiously to guard against the UK becoming a Singapore-on-Thames.

There is no doubt the Commission is gearing up for fastidious monitoring of the withdrawal agreement and the TCA, hence the setting up of two new services in Brussels to oversee that. They clearly feel they have the UK over a barrel with the Northern Ireland Protocol and Barnier insists that it will be monitored and applied rigorously and not renegotiated.

One senses, however, a real concern on Barnier’s part that Northern Ireland could easily become politicised, even weaponised, against the Commission, as evidenced by the EU’s knee-jerk use of Article 16, which Barnier repeatedly described as ‘an error’, that went against all his work on Northern Ireland.

He is at the same time and for the same reason, also sensitive to the issue of the UK’s sovereignty and national borders appearing to be undermined by the Protocol. He corrects Senators who state that the Protocol puts the border between the EU and the UK down the Irish Sea. He protests – too much? – that it does not create a new border, but only customs checks, because, he says, he does not want UK sovereignty undermined. Evidently he is wary of lighting the blue touch paper.

Barnier is very proud of his ‘mirror agreement’, whereby renegotiation of fishing (where the EU is dependent on the UK) will be strictly tied to UK/EU energy connectivity (where the UK is dependent on the EU). This he believes will be strong leverage in fishing renegotiation in a few years time.

Current UK-EU financial services negotiations scheduled to conclude on 31 March are going to be fought hard by the Commission, explains Barnier. The French in particular want Paris to regain its former pre Great War status as Europe’s banker. They were pleased to get the European Securities and Markets Authority moved to Paris from London.

Previous Senate Commission hearings have underlined their ambition, but are conscious of French impediments: bureaucracy, employment law, hostile and erratic tax environment. Macron has attempted to improve employment legislation and also abolished a very political wealth tax. But given French pandemic finances (over 120 per cent debt to GDP) as the 2022 presidentials approach there is already considerable pressure to re-institute the wealth tax and hike others on the corporate sector, not to mention a EU-wide ‘Tobin tax’ on financial transactions.

Barnier’s insistence on learning lessons from why Brexit happened is shared widely by French Senators. They are both concerned that the reasons are not UK specific and could therefore be repeated in another member state. Barnier states as much. This leads to the question of how well the UK will do outside the EU. Some French Senators are not persuaded that the UK will do badly. The implication is that if the UK does well the EU’s coherence and unity may be compromised if lessons are not learnt about Brexit.

The Barnier hearing indicates how strictly the EU and France will monitor the Brexit agreements, but also where their sensitivities lie. France, of all member states, is the most insistent on rigorous application of the agreements. But one detects trepidation about the consequences, with the UK representing France’s largest trade surplus by far, as well as being its closest military partner.

Yet things could be so much worse for the UK. Imagine Michel Barnier defeating Macron in 2022 to become French president and a defeated Macron taking the traditional route of failed national politicians to Brussels to replace Ursula von der Leyen as president of the European Commission. Perhaps that is too pessimistic a thought even in this bicentenary year of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in