‘Try the sports pages,’ said my husband, stirring in his armchair. I was looking for examples of fortuitousused as though it meant ‘fortunate’. You and I know that it means ‘produced by chance’, and it seems a pity to lose the distinction.

The sports pages were indeed thronged with fortuitous. Football, it seems, is a game of chance. It didn’t take long to get a writer in the Daily Mail bang to rights. ‘Only occasionally will you get lucky. Arsenal did ride their luck to down Klopp’s team in London towards the end of last season but may have to wait a while to be so fortuitous again.’

There it must have been intended to mean ‘fortunate’. Of course fortune may be bad, though lucky and fortunate tend to mean good luck and fortune. The verbal roots of fortuitous and fortuneintertwine, but the ancient Romans used fortuitus in just the random sense we do.

The earliest citation of fortuitous in the Oxford English Dictionary, from 1653, is the philosopher Henry More writing about a ‘fortuitous concourse of Atoms’. That was a straight reference to Cicero. I daren’t trespass on the territory of Ancient and Modern, since as a girl I was denied a classical education, but Cicero was opposing the ‘monstrous’ theory of Epicureanism that ‘the sky and earth were formed, not through the compulsion of any natural law, but through a certain accidental concourse [concursus fortuitus]’.

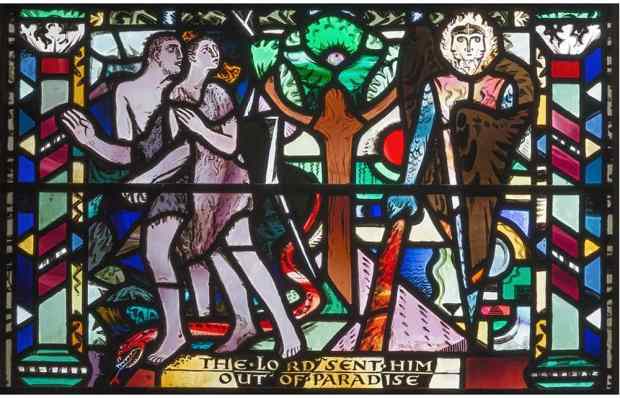

So the fortuitous was not providential, nor even the domain of Fortuna — Dame Fortune as she was known in medieval England — sitting above her wheel of fortune as kings and potentates rose and fell, ‘Now up, now doun as boket in a welle,’ as Chaucer wrote of the affective spirits of lovers. As Ignatius J. Reilly in John Kennedy Toole’s novel A Confederacy of Dunces remarks, taking his cue from Boethius: ‘There was no use fighting Fortuna until the cycle was over.’

You can, I think, insure yourself against fortuitous events, but if, for example, you knew the rotor blades of a machine were cracking, their shearing off would not be fortuitous. An aeroplane crashing into your house would be fortuitous, but not, from most points of view, fortunate.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in