The first full week of the new national lockdown had the potential to be very difficult for Boris Johnson. Although just 34 Tory MPs voted against this England-wide measure, many more are unhappy about it. They have, as Tory MPs now do when they come across things they dislike, set up a group with a three-letter abbreviation: in this case, the CRG (Covid Recovery Group), which will oppose further lockdowns. Adding to the discontent among backbenchers, No. 10 had just U-turned on extending free school meals into the holidays. Tory MPs were left wondering why — as with exam result appeals — they had bothered taking so much flak from the media and the public if the government was going to give way in the end.

But the mood among the Tory parliamentary party is much better than anyone would have predicted a week ago. This is the magic of the Pfizer vaccine announcement. Johnson has attempted to downplay the breakthrough, partly to encourage adherence to lockdown and partly to allay disappointment if there is some last-minute hitch. But the news has persuaded MPs that finally there may be an end in sight to the crisis. As one minister puts it: ‘The problem has been that there’s no light at the end of the tunnel.’ Now there is.

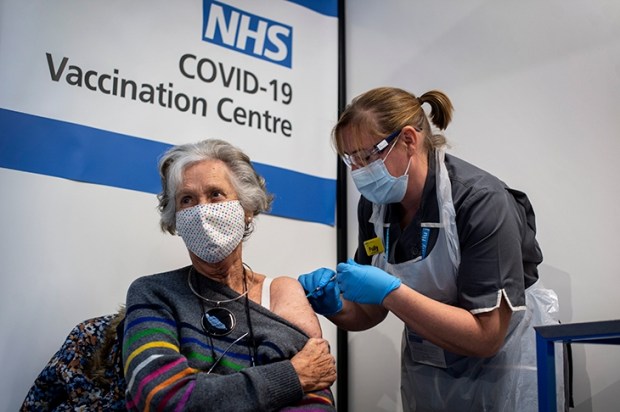

No. 10’s caution is understandable. There are huge logistical obstacles to overcome before the vaccine can be rolled out. It needs to win approval from the regulators (although if it passes the safety test, that should happen quickly). It must also be kept colder than the North Pole until it is sent out to be delivered to patients. But in Whitehall the view is that Pfizer’s vaccine breakthrough will be followed by others because the apparent success shows that a mRNA vaccine (rather than one using a weakened or dead form of the virus) can work. I’m told there are ‘really encouraging signs from pretty much the whole pipeline’ of vaccines. Also, Pfizer’s data showed its trial is far further down the road than the market had believed.

If all goes well, and more than one vaccine is available, the UK will be able to move quickly from vaccinating the most vulnerable to seeking to immunise nearly all adults. But at the moment, the government is talking about only vaccinating half the population. While this could shield those most at risk, it might be cutting it fine in the provision of herd immunity. The current best estimate is that for Covid-19 about 60 per cent of the population would have to be protected — either thanks to natural immunity among those who have recovered from the virus or by a vaccine. In September, the government estimated that 7 per cent of the population has had Covid-19. That leaves quite a gap.

The growing desire in Whitehall to immunise a significant majority of the population is being driven not just by the imperative of returning the economy to normal as quickly as possible, but by mounting concerns inside government about ‘long Covid’ and how it can affect young people who catch the virus.

One of the main worries among many MPs about the second lockdown was that it seemed as if we would be trapped in an endless cycle of restrictions. The decision to impose it appeared to be predicated on the arrival of a medical breakthrough, which was by no means guaranteed. But the vaccine news means it looks more likely that science will offer a solution. Even Tory MPs who voted against this lockdown are feeling better about it. It is now very probable that it won’t be extended beyond 2 December — at least in name. (I understand that after it’s lifted, England may go into a tighter regional tier system than before.)

Now that there is a possible end in sight, ministers are also looking at public perception of the government’s handling of the crisis. The opinion polls are not encouraging: its approval rating is down to 28 per cent. Britain ranks among Europe’s worst-hit countries for both economic damage and Covid deaths. But some in government hope that the work done in securing access to vaccines — and on mass testing — will enable Britain to reopen society relatively quickly compared with other western countries.

We were one of the last European countries to reopen over the summer; next time, it may be different. If so, there would be considerable economic benefits and voters would probably be more positive about government competence. This makes it crucial that vaccine rollout isn’t beset by the same problems that turned the test-and-trace programme into such an expensive flop.

The risk for the government is that it ends up suffering from a political version of long Covid, unable to fully shake off the effects of the disease. One of those who has been at the front line of the response to the virus says that ‘there’s going to be a massive hangover — not just in terms of economic damage, but people’s anger at us’. The pandemic has certainly highlighted a whole series of problems facing the government, but there is now far less money available to deal with them.

Over the next few months, the side effects of lockdown will become more apparent. If exams do happen in England this summer — they have already been cancelled in Wales, as have the Scottish equivalent of GCSEs — they will undoubtedly expose which schools did best in keeping their pupils’ education going during lockdown. This will almost certainly show that existing inequalities have widened since March: the exact opposite of a ‘levelling up’ agenda.

When the crisis is finally over, there will inevitably be a public inquiry. These are rarely pleasant for any government and there have undoubtedly been mistakes, most visibly in the quality of the data used to make decisions. Decisions about, for example, the procurement of personal protective equipment during the worst of the crisis will look very different in the cold light of an inquiry.

But despite these continuing troubles, it seems increasingly probable that by the second half of next year, we will be emerging from this Covid nightmare. The challenge then will be to restore confidence and get the economy and society moving again. This kind of boosterism comes far more naturally to Boris Johnson than the governing style required by the pandemic.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

SPECTATOR.CO.UK/SHOTS

Hear daily political analysis from James Forsyth, Katy Balls, Fraser Nelson and more.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in