In the 1850s Britain was hit by an epidemic likened by The Illustrated London News to a ‘grippe or the cholera morbus’. It came from America rather than China and afflicted the mind rather than the body. The craze for table-turning was sparked in Hydesville, New York, in 1848 after two young sisters, Maggie and Kate Fox, claimed to hear mysterious rappings in the floor of the family home and attributed them to a spirit called Mr Splitfoot.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

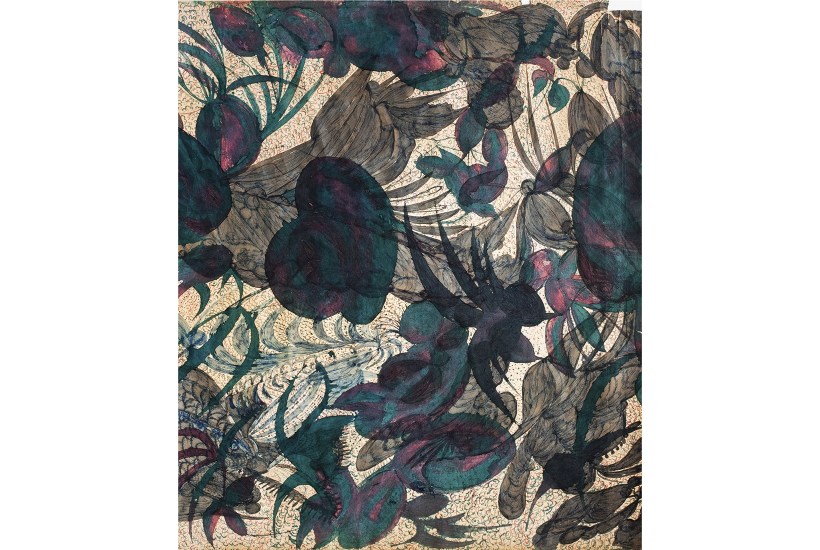

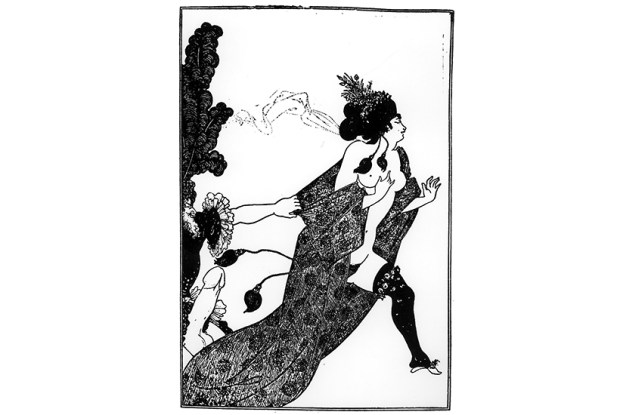

Not Without My Ghosts: The Artist As Medium is at Drawing Room until 1 November (by timed slot, Wednesday–Sunday). The film Beyond the Visible: Hilma af Klint will be released in selected cinemas from 8 October.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in