‘It was the pyres,’ said my husband. He meant the effect of television pictures of cattle, hooves silhouetted against the sky, burnt during the foot-and-mouth outbreak of 2001. It was eradicated by culling six million beasts, not by vaccination producing herd immunity.

In Shropshire, stone memorials survive to the outbreak of rinderpest (like Covid-19 a viral disease) of 1865-67. One outbreak ‘swept 54 head off this farm’ near Market Drayton. ‘They died without remedy and here lie. “Shall we receive good from God and not evil?” Job 2:10.’ Nationally, 289,581 died.

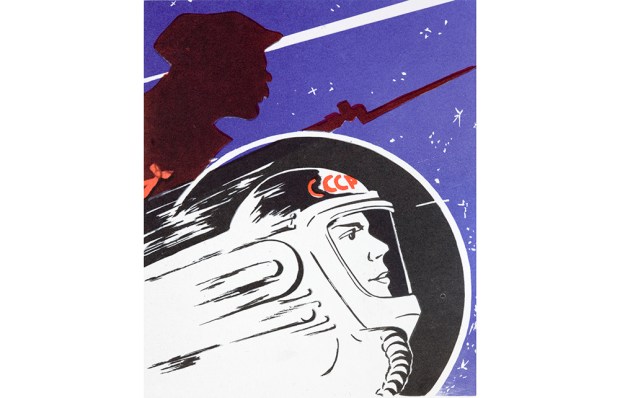

Britain had met the three big 18th-century cattle plagues by paying farmers to slaughter sick animals quickly, a policy pursued from 1714 by Dr Thomas Bates. This murrain, later called rinderpest, recurred. In south and east Africa it killed 80 per cent of cattle in the 1890s. Only systematic vaccination saw it off. The last phial of rinderpest virus was destroyed at Pirbright in June 2019. Vaccination produced herd immunity and the virus died out.

Yet, as my husband suggests, slaughter remains connected with that word herd. Flock is friendlier, partly through scriptural associations: ‘The Lord is my shepherd.’

In March, the Oxford English Dictionary introduced herd immunity to its pages. Its first citation, from 1917, is from a paper by two American vets on infectious miscarriage among cattle. They proposed not slaughter but keeping cows that survived and any calves born, to establish a ‘herd immunity’.

Aware of the sins of eugenics, some historians have shivered at the extension of herd immunityto human beings — such as the boys of the Royal Hospital School in Greenwich during diphtheria outbreaks. Of them, Professor Sheldon Dudley used herd immunity in the Lancet in 1924. He did not favour slaughtering the boys but vaccination. In 1928 it was found that older boys, exposed to past outbreaks, developed immunity more rapidly when vaccinated.

The NHS website says: ‘If enough people are vaccinated, it’s harder for the disease to spread to those people who cannot have vaccines.’ That is herd immunity, though few dare speak its name.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in