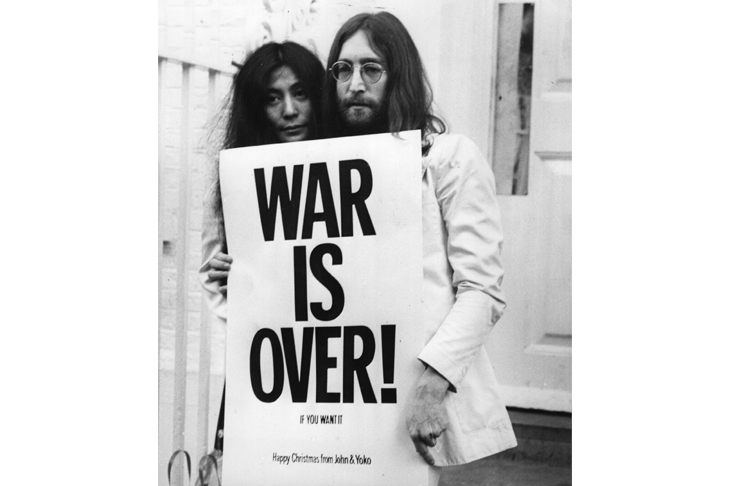

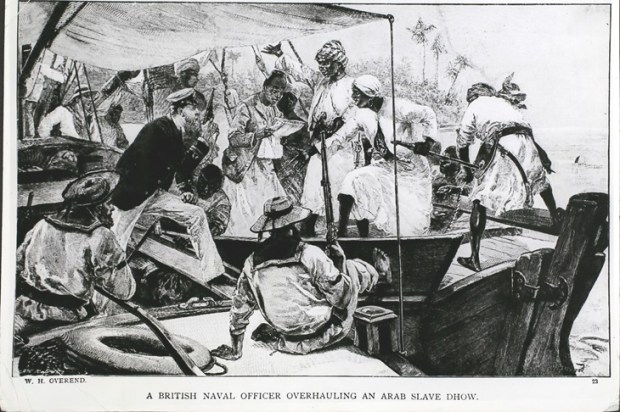

Forming groups to kill other groups over territory, resources or belief is so much a part of the human condition that when a nation is denied those traditional casus belli it will often deploy martial terminology in places where armies have no obvious role. Thus, the ink had barely dried at Yalta when a bunch of bleeding-heart Brits, undeterred by the irony of including one of the main causes of third world poverty in the name of a charity dedicated to its relief, declared a War on Want.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in