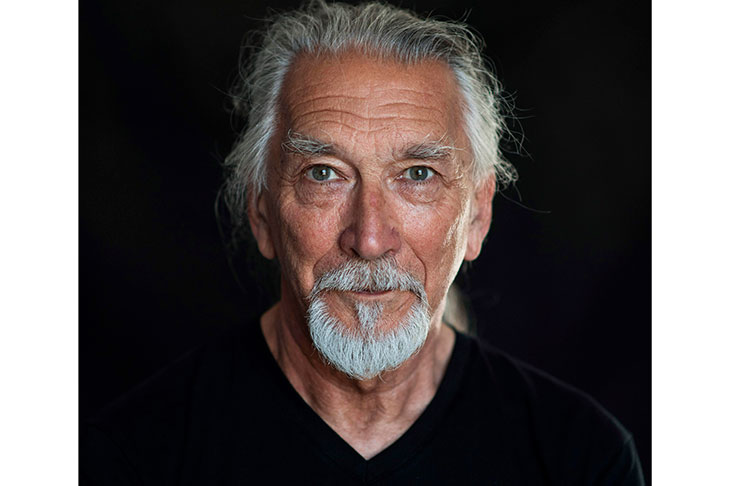

Over the past 50 years, M. John Harrison has produced a remarkably varied body of work: a dozen atmospheric novels and five volumes of finely controlled short stories that have ranged from austere realism to operatic fantasy.

He is not easily pigeon-holed — an intentional state of affairs, but one that has denied him a large readership. The worlds of his science fiction are truly strange, yet he conjures them with piercing lucidity. For instance, Light (2002) is largely set 400 years in the future. The cosmos Harrison visualises is a place of splintery disruptions, but it is peopled with cruel and slovenly characters whose minds churn in entirely familiar ways. When he moves into less exotic terrain, he’s able to make everyday experiences feel alien — the best example being his 1989 novel Climbers, set in the Pennines among misfits who claw their way up crags, escaping one kind of precariousness by chasing another.

The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again, his first novel for eight years, is low on incident but richly textured. A vision of dark energies pulsing beneath Britain’s streets, it feels slippery and seedy. The title derives from a lecture by Charles Kingsley, Victorian Britain’s leading advocate of Christian socialism. Kingsley spoke of ‘a great change in the climate of this country’; and in the rheumatic contemporary Britain that Harrison depicts this is both literally and figuratively the case. The waters are rising, and so is a tide of paranoid distrust.

The main character is Shaw, a man in his fifties recovering from what he considers a ‘period of retraction’. He lives modestly in a shared property in East Sheen and occasionally visits his senile mother in her care home nearby. Pleasure of a fidgety sort derives from his entanglement with Victoria, an ‘eroded’ romantic who works in a morgue. She soon moves, after inheriting a house in Shropshire, and the new surroundings make her skittish, aware of phantom voices. ‘It’s a nice little town,’ she reflects, ‘but something is happening here.’

The couple’s on-off relationship plays out against a backdrop of political and social upheaval, to which they are amusingly unattuned. Shaw, a pawn in the gig economy, is taken on to perform various chores for Tim, the proprietor of a crankish website called The Water House. He finds himself acting as a travelling salesman, peddling a book that purports to be about genetics but is really a catalogue of urban myths and pseudoscientific guff.

Meanwhile, there are increasingly heavy hints that a new species is emerging, green and fishlike. A man on trial for violent disorder — in truth nothing worse than shouting in the street — reports having seen ‘something alive in the water’ in the urinal at his local pub. This turns out to possess ‘the qualities of both a foetus and a fully formed organism’, and he flushes it away in disgust.

Similar sightings follow, and copies of Kingsley’s The Water Babies begin to appear in unlikely places. This morality tale, which is also a primer in aquatic biology, becomes a sacred text for a society preoccupied with ideas of submersion, metamorphosis and regression. The gaps between the characters are of more interest to Harrison than their skulking intimacies, and things seen from the corner of the eye matter more than those observed directly. The result is a disconcerting portrait of a Britain plagued by suspicion and conspiracy theories.

The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again contains echoes of ‘Running Down’, a Harrison story from the 1970s in which an angry new form of patriotism is causing the country’s established structures to buckle. It is one of 17 in Settling the World, a selection spanning his whole career. All are elegant and inventive, and most involve an uncanny swerve. The prose ripples with mystery and lustrous turns of phrase, and there are flashes of humour, too — the tension in an old man’s face ‘might have been vegetarianism or pain’.

The landscapes are part J.G. Ballard, part Iain Sinclair: a rutted wasteland of building sites, streets ‘like a long declining dream’, untenanted blocks of flats and bedsits with one-bar electric fires. The characters who haunt them include beachcombers and bureaucrats, marooned adventurers and posturing undergraduates who resemble ‘dowdy flamingos’. The humdrum and the fantastic are in close conversation: a couple discuss quantum theory while eating pizza, and the gateway to a paralysed, almost medieval, future is found round the back of a restaurant in Huddersfield. Equally at ease depicting suburban midlife crisis and parallel universes, Harrison writes memorably about people who are bewildered, sidetracked, trapped or on the lookout for opportunities to change.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in