Like so many of us in these troubled times, I am worried about the family statues.

The topple-mob cannot be reasoned with in this most irrational of revolutions, which insists on racial confrontation despite furious moral agreement that all black lives matter, George Floyd’s in particular. It insists on fabrications about the higher rate of indigenous versus white deaths in custody – false, says the Institute of Criminology – and it laments the alleged injustice of having so many blacks in prison.

Alas, justice is colour blind, so when an Aboriginal woman is thirty times more likely to end up in hospital for domestic violence, her man is more likely to end up in jail. Let’s march for #BlackWivesBattered; that would be based on a terrible truth, not intensely felt falsehoods.

Failing those falsehoods, there’s always the slave trade to fall back on! At least that cesspit can be used to smear all white men as evil racists.

Once again, false. The family statues I have in mind commemorate the best white brothers the black man ever had. They counter the Marxist #BLM movement’s demoralising slander of our culture and say what needs saying: that our colonial history has as much honour as shame.

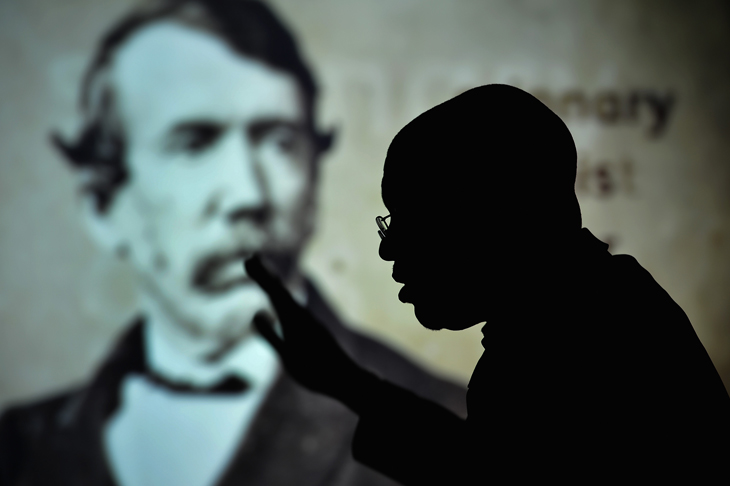

Three-greats grandfather Robert Moffat, whose memorial stands in Ormiston, Scotland, founded a real #BlackLivesMatter movement two hundred years ago in the Kalahari desert. For fifty years he served the Tswana people at Kuruman, enduring dangers and privations that today’s pampered protesters know nothing of. He stood with the Africans against the marauding Boers; he taught them agriculture and freed them from the spiritual terror of the witch doctor; he brought a printing press to the desert and produced the first New Testament in an African tongue, because #BlackSoulsMatter. He also brought out a young medical missionary, David Livingstone, whom he met during a fund-raising tour of Britain in 1840. He writes:

By and by he asked whether I thought he would do for Africa. I said I believed he would, if he would not go to an old station but would advance to unoccupied ground, specifying the vast plain to the north where I had sometimes seen, in the morning sun, the smoke of a thousand villages where no missionary had ever been.

Livingstone trained at Kuruman, proposing to Moffat’s daughter Mary under the almond tree – you can still see the stump. Then it was off north to the smoke of a thousand villages and the smouldering foulness of the Arab trade in African slaves, the destruction of which became Livingstone’s lifework. His statue still stands by Victoria Falls; the Africans know who their friends are.

Those decades saw the English-speaking world achieve the greatest movement for moral good in any culture in any age, as they exorcised the ancient evil of slavery. Someone should build a statue to these dead white males.

In 1833, Christian Britain passed Wilberforce’s Emancipation Act, abolishing slavery throughout the Empire. From the 1850s to 1870s, Livingstone used his growing fame to pressure the British government to send in troops to drive out the Arab slave traders. Across the Atlantic in 1865, Abraham Lincoln’s troops cauterised the open sore of slavery in the South; tragically, Livingstone’s eldest son Robert died in Lincoln’s army as a prisoner of the Confederates.

So much for the good guys, but what about Cecil Rhodes, that arch-villain of imperialism? His statue at Oxford, where he was a one-term dropout and incomparable benefactor to students of all races, triggered the #RhodesMustFall campaign as the prototype of all subsequent topplings.

Livingstone’s brother-in-law, John Smith Moffat, became a fierce opponent of Rhodes after the mining magnate violated a treaty with Moffat’s friend, Chief Lobengula of Matabeleland. Others shared his low opinion of Rhodes: Mark Twain said, ‘I admire him, I frankly confess it; and when his time comes I shall buy a piece of the rope for a keepsake.’

Yet there was greatness in Rhodes, as historian Paul Johnson acknowledged, with his passion for extending the benefits of British civilisation ‘from Cape to Cairo’. There was some goodness; he quietly funded the education of Lobengula’s son, Njuba, and race was never a criterion for his scholarships. There was courage; in the second Matabele war he walked unarmed into the Chief’s stronghold to urge an end to hostilities. He earned respect from former enemies; at his burial in their lands in 1902, the warrior-heirs of Lobengula gave the royal salute and even Robert Mugabe preserved his grave as an essential part of Rhodesia/Zimbabwe’s history.

Should small self-righteous students be allowed to topple Rhode’s statue at Oxford; students who have done nothing more courageous in their life than shout ‘f— the police’ at rallies; students who condemn Rhode’s arguable claim of British cultural supremacy while urging the state-enforced supremacy of Greta’s green globalism and a borderless, genderless Gaia; shabby students who condemn their forebears for taking profit from slaves while taking pleasure themselves from present-day slaves trafficked in the porn fields of the internet?

It is precisely because of decades of cultural self-loathing instilled in such students that the perverse Western urge to topple our past is now so strong. True, ‘there is a great deal of ruin in a nation’, as Adam Smith said, because there is a great deal of ruin in each of us who make up the nation. But there is also great good. The one-sided dwelling on cultural failings is a sickness, possibly terminal, and needs radical treatment.

I suggest an eye transplant. Let’s give our young people different eyes for looking at our nation’s history: eyes of compassion instead of morbid rage. Only compassion can look steadily at the shame and the honour of a nation (or a person) and still find reason to love and pity it – precisely because it understands that all history, being human, is a tragic mix of striving for good and sinking into evil. That’s the way we are. Let him who is without sin topple the first statue.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in