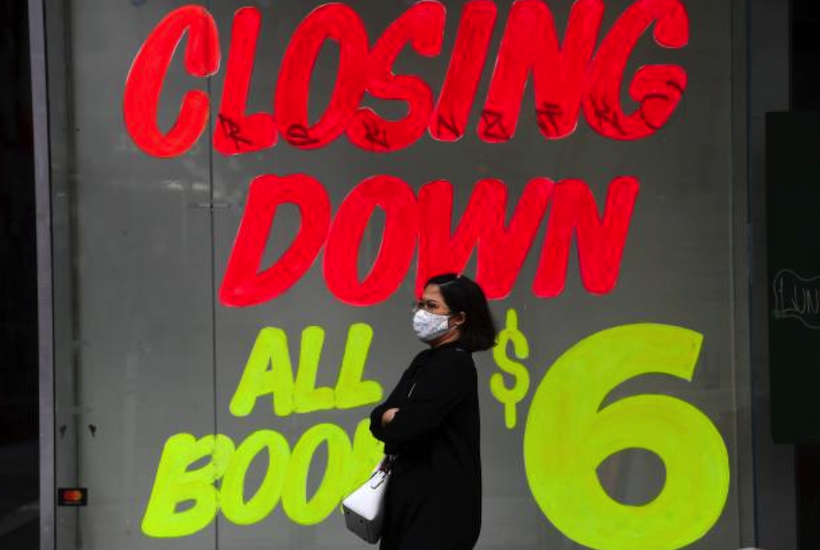

The coronavirus, the political risk event of our generation, will change many things. Not least of these is the sufferance of illogical, highly detrimental economic philosophies of the world, ideologies that—given that we are at present desperately trying to stave off global depression—Australians can no longer afford to tolerate.

First and foremost amongst these is the European Union’s championing of the precautionary principle, which they make no bones about exporting to the rest of the world. The precautionary approach—entirely at odds with the Australian, American and the likely future British approach to regulation — means that merely the suspicion of the harm a product can do in the future, not necessarily based on any empirical real-world evidence at all, is enough to doom it.

By virtue of the fact that I have lived in Europe over the past 14 years, I have had a front-row seat as to the misapplication of the precautionary principle, and the predictable economic sclerosis that has followed.

The precautionary principle exhorts governments to set standards and act vigorously to outlaw products if they merely suspect something may go wrong, a far lower burden of regulatory proof entirely open to the subjectivity and bias of the regulators, often over environmental or health grounds.

It holds that where there is an action, product, or policy that might cause harm to the public, even if that harm is far from a certainty, the burden of proof falls on those who advocate for them. In other words, under the precautionary principle you are guilty until proven innocent. As Bjorn Lomborg put it so well, ‘Nothing can be proven to be un-dangerous.’

In a utopian effort to somehow do entirely away with risk, the precautionary principle ignores the obvious reality that this can simply never be accomplished. For example, and entirely pertinent given our present global Health Care crisis, in the past the precautionary principle would have banned the development of vaccines, precisely on the ground that in a few cases they can cause side effects, and rarely can even cause death. To halt this handful of real deleterious effects, hundreds of millions of lives would not have been saved. Frankly, this is lunacy.

A second example concerns the EU’s present over-the-top efforts to manage human health and environmental risks presented by certain chemicals under its law, commonly called REACH. Many of these substances have already been extensively studied and used in Australian commerce (and elsewhere) for decades.

These manufactured materials are essential for many modern technologies that drive progress, from electric car batteries to energy-efficient LED (light-emitting diode) lights to wind turbines and solar panels, all of which help with Australia’s environmental concerns.

The EU’s regulatory approach, based entirely on the precautionary principle, stands in direct contrast to Australia and Canada, both of whom regulatorily assess chemicals using a risk-based approach and all available science. Following the EU’s logically flawed and consumer-unfriendly precautionary principle, in general, would hobble Australia’s dynamic economy, especially at a time when Covid-19 is destroying the global economy.

Rather than following the EU along the path to economic sclerosis and regulatory lunacy, far better for the developing world to embrace a very different cost-benefit model. Instead of curbing innovation, Australia and much of the Anglo-Saxon world rightly adheres to the cost-benefit paradigm of regulation, forcing bureaucrats to outline all the benefits of a product, as well as its possible dangers.

This real-world approach, however, is entirely at odds and under assault from the EU. Australians and other like-minded nations must defend the cost-benefit paradigm, as only its common sense weighing of advantages and dangers corresponds to the reality that regulators must actually deal with.

The EU’s drastic regulatory actions provide a cautionary tale for governments around the world—such as Brazil, China, India, Japan, and South Korea—which are considering their own future regulatory structures; their aping of the logically flawed and consumer-unfriendly precautionary principle would hobble their far more dynamic economies. Worse, from an Australian point of view, many of these Asian countries are major trading partners, which—if they adopt the precautionary principle–will over time undoubtedly impinge on both Australian trade and regulatory norms themselves.

Anyone doubting what I am saying need only consider the economically sclerotic real-world record of the EU over the past decades; it is little short of disastrous, and should not be copied by anyone serious about economic growth.

Let the concrete facts about the EU speak for themselves. Even before the coronavirus plague descended, the Eurozone was economically sclerotic—growing by a paltry then per cent of GDP last year, with powerhouse Germany managing only 0.5 per cent and pathetic Italy doing even worse. In fact, tellingly, Italy’s economy is about the same size today as it was in 2000, just after it joined the euro-zone. To put it mildly, no one alive should want to copy the EU’s objective economic record over the past generation.

Yet that has not stopped the European Commission from aggressively trying to export its record of failure to the rest of the world, in the guise of forcing others to accept the precautionary principle as the basis of common regulatory free trade deals, while attempting to enshrine it in international treaties. Australia must take the lead in Asia, seeing to it that its safe, science-based, but more consumer-friendly regulatory model wins out, urging its Asian trading partners to adopt more sensible, growth-oriented norms.

Regulators around the world should adhere to these superior principles to produce the best, most effective regulations that simultaneously protect human health and the environment, while promoting innovation that powers economic growth and consumer choice. Guided by such regulatory success stories such as Australia, countries currently considering their future regulatory regimes should be wary of both the EU, and the ill-judged precautionary principle that it is peddling.

Instead, to both protect safety and power global growth to ward off the threat of global depression, they should embrace the market-based, real-world, cost-benefit based regulatory systems pioneered by Australia, Canada and the US. The world is in too great an economic peril for the unseriousness of the precautionary principle.

Dr John C. Hulsman is the president and managing partner of John C. Hulsman Enterprises, a prominent global political risk consulting firm, headquartered in Milan, Germany and London. A life member of the US Council on Foreign Relations, Hulsman is also Senior Columnist at City AM, the newspaper of the City of London.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in