To Hongkongers, Britain’s coronavirus response is nothing short of a disaster. Since I began self-isolating in London days before the official lockdown started on 23 March, I’ve received dozens of messages from loved ones back home in Hong Kong expressing their concern – and incredulity.

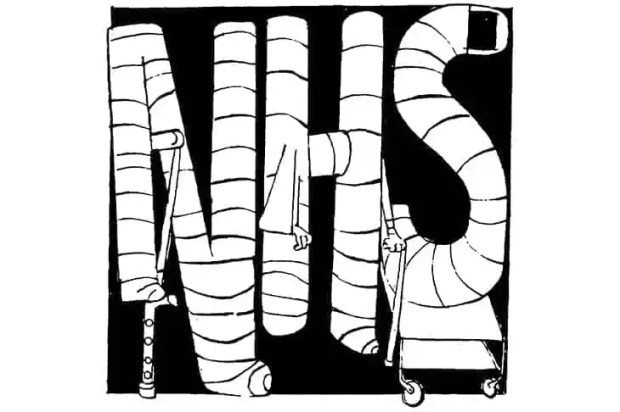

Despite advance warnings since January of how serious the situation was in Asia, the UK’s initial approach was slow and lax even compared to many of its European counterparts. The choice to offset infections by mitigating rather than controlling the virus allowed it to spread unchecked and likely condemned the economy to a protracted lockdown, as well as a tragically higher death toll. Confusion over the government’s stance on herd immunity, reluctance to implement harsher restrictions, PPE shortages, disinformation and the recent lack of clarity over updated social-distancing advice have since made a spectacle of Britain for all the wrong reasons.

The death toll has risen to over 40,000 in the UK – the highest in Europe – and 5,782 in London. By contrast, in Hong Kong – a densely-populated city with over seven million people (approximately two million less than London) bordering mainland China where the initial outbreak took place – the death toll is four.

One key difference between Hong Kong and the UK is that Hongkongers did not wait for the government to respond. From the get-go, residents spontaneously adopted near-universal masking and began grassroots organising to spread public hygiene messages – as well as fix medical shortages – without prompting from the government, which last year imposed a mask ban during pro-democracy protests.

People protested for the closure of borders with China, chose freely to isolate themselves during the initial outbreak and took precautions way beyond government recommendations. My family disinfected their shoes, cleaned their groceries with disinfectant wipes and showered every time they returned home when the virus was at its peak. The recent threat of imported cases also led the city to shut itself from non-residents. Everyone who flies home is tested before being sent into compulsory quarantine with tracking bracelets. As such, the city never needed to completely ‘lock down’, and residents have been able to go about their daily lives in relative freedom.

In many ways, Hongkongers are used to trauma and having to rely on ourselves. Most of us are descendents of refugee families, survived SARs and have been embattled by years of rising inequality and political unrest. While the coronavirus has become yet another political battleground in Britain, it has in a sense functioned as a momentary, unifying threat for Hongkongers during a period of escalating political divide.

In London, my experience has been drastically different. When my friends from Asia and I began isolating and wearing masks, we suffered abuse from strangers and our British peers accused us of overreacting. My boyfriend, an NHS doctor, recalls cycling to work the night before the lockdown and seeing pubs filled with revellers. The UK government’s failure to tackle the crisis and the relative reluctance amongst some Brits to compromise on civil liberties for the sake of public health have triggered debate over why attitudes towards the crisis have differed so drastically between the two communities. Did the government simply not have enough faith in the British public to follow necessary rules? Is British exceptionalism at work in preventing some from taking the virus seriously?

Whatever the reason, there is a marked difference between the way Brits and those from other countries — particularly Hong Kong and other parts of Asia – view the UK’s response.

While new polling indicates that public confidence in the government’s ability to manage the crisis dropped since the easing of lockdown restrictions and that Brits are becoming more wary of the illness, an Edelman poll released earlier this month indicates a huge leap in government trust, which peaked at an all-time high of 65 per cent as the pandemic was taking hold.

Among young British people I’ve spoken to, few seem concerned about falling ill. In the UK, the view that only the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions become gravely sick – perpetuated by discussions on herd immunity – persists, leading to growing calls for the lockdown to end, on the basis that it causes more harm than the virus itself.

In some ways, international comparisons of pandemic responses are unhelpful because they take each approach out of context. Hong Kong’s response has not been faultless, and many British people have taken matters into their own hands to fill the gaps left by authorities. Compared to the UK, Hong Kong’s public health system is perhaps more equipped to tackle a prolonged pandemic, particularly after SARs. One British friend points out that the UK is larger and more diverse than Hong Kong, and there is a richer tradition of intellectual debate as well as respect of opposition.

But there are lessons to be learned, and cultural relativism alone should not be used to excuse Britain’s terrible death toll.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Jessie Lau is an international journalist from Hong Kong. She tweets @_laujessie

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in