‘Plunderers of the air’, Naum Gabo called the Luftwaffe planes. In Cornwall, during the second world war, Gabo kept cuttings of the attacks over London. One newspaper photo, pasted in his diary, was taken from the Golden Gallery of St Paul’s after a night of incendiary bombs. London looks like Pompeii. Enemy planes were a betrayal.

Gabo was entranced by flight. His sculptures are spiralling tributes to air, light and lift-off. After an hour in the Naum Gabo retrospective at Tate St Ives, the first major show of the artist’s work for more than 30 years, you feel a certain springiness about the knees as if you could push off Porthmeor Beach and fly. The Icarus effect.

Born Nehemiah Pevsner in south-west Russia in 1890, Gabo studied medicine, natural sciences and philosophy in Munich, before returning to Russia in 1917 where he practised as an artist in the all-things-possible period that followed the Russian Revolution. He worked in Norway, Paris and Berlin. Gabo, a Russian citizen of Jewish descent, left Nazi Germany for Paris in 1933 before coming to London in 1936 where he lived in Hampstead not far from Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. In 1939, Gabo and his wife Miriam followed Nicholson and Hepworth to Carbis Bay along the coast from St Ives. Gabo and Nicholson became local air-raid wardens watching the skies by night. Off-duty photographs show Nicholson and Gabo on the beach with Gabo’s dog Snezhka (Snowball). Gabo’s daughter Nina was born in Cornwall. The family moved to America in 1946.

In the first room of the show you are met by the monumental centurion’s helmet of Gabo’s ‘Head No. 2’ (1916). If you saw the Henry Moore helmet heads at the Wallace Collection last year you’ll be struck by the contrast: Moore molten, domed, pooling in hollows; Gabo metallic, mechanised, split into tail-fin cheeks, mineshaft noses, shovel chins and propeller shoulders. The ‘Head’ is a steel figure of hunched, jutting angularity. Gabo scalpels the surface to expose the ribs, tendons and fine veins of form. Like a clockmaker, he separates the parts. Many of his sculptures have the tick-tock workings of cogs and pendulums. They recall orreries and armillary spheres. His fountains throw off water in arcs and parabolas. Gabo’s whetstone work is so sharp you’d cut yourself. Edges slice the air like mandolines. A Hepworth draws you into its centre; a Gabo spins you away with centrifugal force.

If that makes Gabo sound chilly — certainly my former view — this show makes the case for a gentler artist. Not a new Euclid, but an artist responding to nature. Once you stop seeing rockets, you start seeing wings. His ‘Bronze Spheric Theme’ (c.1960) is like a butterfly fluttering above its plinth, his ‘Linear Construction No. 2’ (1970–1) like a hummingbird’s blur. Gabo’s Perspex becomes amber. His ‘Construction: Stone with a Collar’ (c.1936–7) has the smooth, pleasing edges of skimming stones for ducks and drakes.

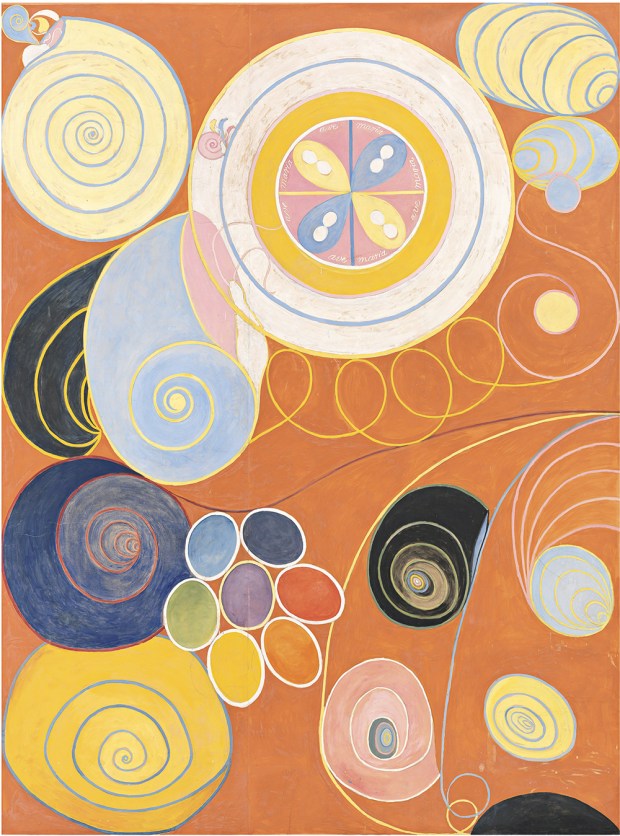

Gabo gives us games, too. An intellectual exercise in axes becomes a helter-skelter, a pool slide, a spinning record, a cat’s cradle, a Spirograph. I remember the delight of a school maths class in which we were taught to join the corners of a graph with straight lines that made, at their intersections, a sweeping curve. Magic.

For his daughter Nina, Gabo made the ‘Constructivist Ballet’ (1940). Toys and art materials were scarce in wartime and so Gabo took scraps of coloured plastic and foil and fashioned them into coils, figures and Japanese lanterns as small as your smallest fingernail. He made a miniature stage under a Perspex dome. By rubbing the dome with a duster to create static, the pinhead figures danced. It was, Nina remembers in a video, a ‘teatime treat’ only to be played with under ‘tremendous supervision’. There’s an exhibition to be done, surely, on the make-do-and-mend works of artists in war. See also Picasso’s spectral creatures cut out of paper napkins in the Royal Academy’s current show.

In 1927, Gabo and his brother Antoine Pevsner designed a ballet for Sergei Diaghilev. La Chatte borrowed from Aesop’s fable of a man who falls in love with his cat. The dancers carry shields of circles and squares, the principals wear rhomboid fascinator hats. It’s Pythagoras en pointe. Gabo’s plastic leggings (hot, sticky) were firmly discarded in rehearsals. Many of the works have a musical thrum. Quite literally, in the case of the motor-powered ‘Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave)’ (1919–20). Push a button and the metal rod shimmies. Gabo’s stringed sculptures are uncanny harps, almost-ghosts of former instruments.

A little more curatorial handholding wouldn’t hurt. The architecture section is underexplained and not every visitor will know their Realistic Manifesto from their constructivist mission statement or their stereometrics from their Soviet monuments. Swot up on the flight from Heathrow to Newquay — and choose a seat over the wings.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in