Though Scots are doubtful about secession from the UK, Scots literary figures and intellectuals are likely to be strongly, even aggressively, for it. Conspicuous in this is Anglophobia, which is a default position for many. At an extreme, it amounts to a rejection of the English and Scots unionists which conjures up the rhetoric of racial hatred.

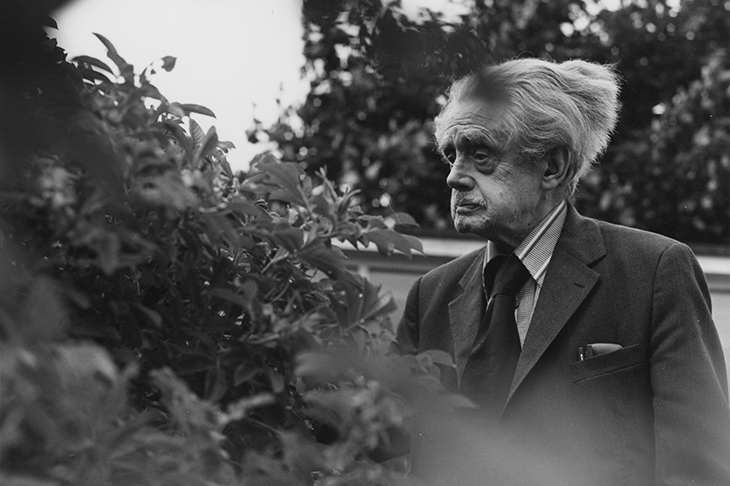

The influence of two large 20th-century figures has soaked into the Scots literary ground. These are the poet and polemicist Hugh MacDiarmid (1892-1978), and the intellectual Tom Nairn (born 1932). They have a close disciple in the figure of the novel-ist James Kelman (born 1946), the only Scots Booker Prize winner in the past half-century.

In an interview a little before his death, MacDiarmid said that when he was in the army medical corps in the first world war, he and the Irish and Welsh recruits ‘didn’t get on with the English at all… and I became more and more anti-English as time went on’. He wasn’t kidding. In 2003, the researcher John Manson found, among MacDiarmid’s papers in the National Library of Scotland, notes and poems (unpublished) written in the first years of the second world war, which included a verse — ‘The leprous swine in London town/ And their Anglo-Scots accomplices/ Are, as they have always been/ Scotland’s only enemies’. In a note, he looked forward to the destruction of London — ‘earth’s greatest stumbling block and rock of offence’.

He was attracted to Mussolini, and more distantly to Hitler, in the 1930s, and saw democracy as a barrier to ‘the real will that bides its time’ — that is, of an enlightened dictator. He is still held in reverence in much of literary Scotland and his ingrained authoritarianism is rarely questioned — neither is the scorn in which he held Scots, sneering at ‘the moronic quality of most of our people’.

Tom Nairn worked in a different register to engrain a national aversion to the English. In two books — The Break-Up of Britain (1977) and After Britain (2001) he pictures England as a failed state — failed in not having a ‘proper’ revolution, as did the French, failed in developing a properly critical intelligentsia, failed in producing a vibrant and successful capitalism. Commenting on his work, the early part of which is in collaboration with the editor of New Left Review, Perry Anderson, the Northern Irish scholar Arthur Aughey writes that it was distinguished by ‘its hostility to any flow of sympathy with English culture’.

In The Break-Up, Nairn sees the British state as ‘a sinking paddle-wheel state’, ‘an indefensible and inadaptable relic, neither properly archaic nor properly modern’. England suffers from a ‘long-term irreversible degeneration… within the hopeless decaying institutions of a lost imperial state’. The belief that the English cling to the idea of empire has been widely picked up by Scottish and especially Irish intellectuals and commentators as a major reason for the popularity of Brexit in England — without any real evidence of it being the case.

In one passage, Nairn describes England as one full of ‘malign Euro-scepticism… (and) brutish prejudice or post-imperial exclusives’ — and also as ‘the country of Stephen Lawrence’ — a casual slur to tar the English with the violent racism which animated the gang of white youths who murdered the black teenager in south-east London in April 1993. There was widespread disgust in England over the murder and the lengthy inability of the police to bring a conviction, while the Lawrence family was strongly supported — his mother, Doreen Lawrence, was given a peerage, a Stephen Lawrence Centre was opened, and with it a Stephen Lawrence Trust.

The positioning of England as hostile to people of colour and to immigration is a major Scottish National Party trope, even though England has, proportionately, by far the largest population of immigrants and their descendants in the British Isles. Nairn can fairly be said to be a major influence on the ritual mendacity of SNP rhetoric when it addresses the English question.

The most prominent literary Anglophobe is James Kelman, whose novel How Late it Was, How Late (1994) won — controversially, in part because of its thick scattering of profanities, though it is in my view a fine novel — the Booker Prize. In an essay in a 2012 collection, Kelman follows MacDiarmid and Nairn in the intensity of his Anglophobia: the English exercise a ‘supremacist ideology’ and all who oppose it are dismissed as ‘not being properly patriotic’. Echoing MacDiarmid, he writes that ‘the (Scots) bourgeoisie tend to go with the colonisers and the imperialists (the English) as a means of personal and group survival and advancement’.

He claims he reads no English fiction ‘because of the class barrier. Why would you want to read things that were treating you as an animal?’ In fact, the complaint which could be made of contemporary English literary fiction is that it hardly ‘treats’ Scots at all. The one passage from 20th-century English novels which is widely remembered is that from P.G. Wodehouse’s Blandings Castle — ‘It is never difficult to distinguish between a Scotsman with a grievance and a ray of sunshine’ — once quoted at me, to my irritation, by the historian Peter (Lord) Hennessy after I had given a pessimistic assessment of the future of newspapers. But I can think of no novel, or any piece of English writing, which treats contemporary Scots as animals.

That charge is absurd, but indicative of a frame of mind, strongly present in the SNP, which has a need to see Scots as oppressed, cheated and ignored by the English, a mindset which, as Robert Burns has it in ‘Tam O’Shanter’, ‘nurses her wrath to keep it warm’. The emptiness of much of SNP propaganda is increasingly evident, even as they continue to dominate Scottish politics. Yet the self-pitying themes they borrow from the large figures of 20th-century Scots literature and polemic are among the most damaging, above all to the Scots themselves.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

John Lloyd’s Should Auld Acquaintance Be Forgot: the Great Mistake of Scottish Nationalism is published next month.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in