It is often the small constants in the culture that give the game away. Much of the news today is not about anything significant, but rather a sort of lower gossip. Every day, some new scandal bubbles along. Someone is found to have said something once, often a long time ago. The culprit is shamed and condemned.

Take the case of Frank Hester, a donor who has given an estimated £10 million to the Conservative party. Few had heard of him until recently. Then it was reported that at a meeting at his company headquarters in 2019, Hester said that Diane Abbott MP made him ‘just want to hate all black women because she’s there, and I don’t hate all black women at all, but I think she should be shot’. Cack-handed, and unfunny, this comment was an easy one to condemn. Hester was widely criticised and he swiftly apologised, adding that his remarks ‘had nothing to do with [Abbott’s] gender nor colour of her skin’.

You only have to put one step wrong to be wrong for ever

But the story wouldn’t go away. Kemi Badenoch accurately said that it was ‘pure media bubble speculation’. She went on to say that ‘we need to get to a place where we stop chasing people around and looking everywhere for the racism’. That memo didn’t reach the media or the many people who want to make life as difficult as possible for the present government. Having first refused to censure the comments, the Prime Minister was soon forced to do so, insisting they were ‘racist and wrong’.

There it might have stopped. But some people don’t want to let such things stop. Abbott claimed that the remarks were ‘scary’ and last week she reported Hester to the police. West Yorkshire officers say that they’ve now set up an investigation into the alleged comments. Which I’m sure everyone agrees is another superb use of police time.

You might say that this is merely an inevitable part of the political game. If Hester had donated to the Labour party and the words been said about, say, Badenoch, I suspect that Abbott’s ire might have been lesser. Labour MPs of course have a track record of making inflammatory comments themselves, whether it’s green-lighting anti-Semitism (Abbott) or denouncing their political opponents as ‘scum’ (Angela Rayner). In these cases, they had semi-apologies dragged out of them and insisted that every-body move on. It’s a standard they expect for themselves, but not one they apply to others.

Small fry though the Hester story might be, it points to something deep going on in our culture – because we live in a time when people’s private and public thoughts can be spread around the world as never before. In-group behaviour no longer stays with the in-group. Thanks to social media, anything can also be discovered by an out-group, which may comprise almost everybody in the world.

We have never had to deal with anything like this before. Any mistake can rear up in front of you again – whether five years later (as with Hester) or decades on (as it was for my colleague Toby Young a while back).

People gleefully rake over the outrage. For many, it gives life a meaning of a sort. And as we know, in the social-media era it has not only managed to bring down the odd famous person; it has done for those who were previously private individuals. It has destroyed everyone from supermarket workers to schoolteachers to a lady-in-waiting.

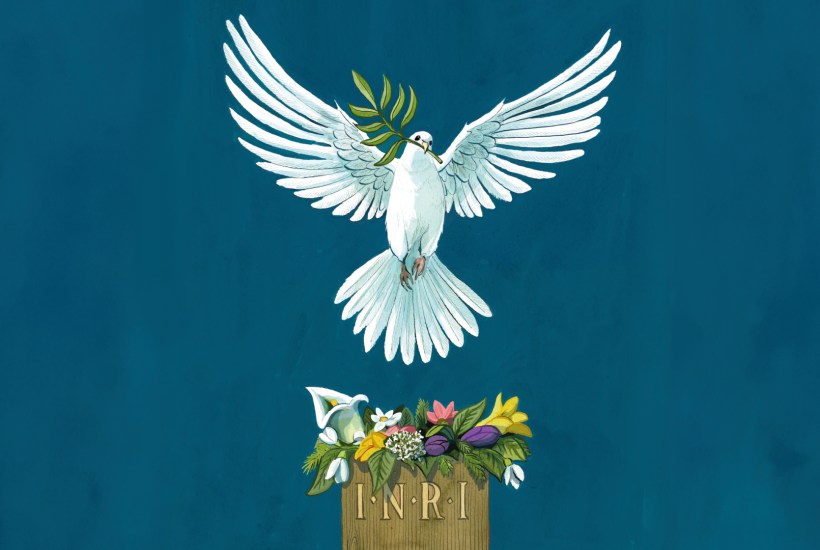

Clearly people enjoy the thrill. Because it is thrilling. But what they have failed to consider is that they are abandoning one of the most important ethical beliefs in our whole Judaeo-Christian civilisation: forgiveness. And not just forgiveness for people you like and eternal damnation for anyone you don’t. But forgiveness available to all.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt addressed this issue 60 years ago in a remarkable lecture delivered at the University of Chicago titled ‘Labour, Work, Action’ as part of a conference on ‘Christianity and Economic Man: Moral Decisions in an Affluent Society’. The main subject of Arendt’s lecture was what an ‘active’ life consists of. Towards the end she reflected on one of the unavoidable consequences of being active in the world: that we cannot know what the consequences of our actions are. The ‘frailty and unreliability of human affairs’ means that we are constantly acting in a ‘web of relationships’ in which ‘every action touches off not only a reaction but a chain reaction’. As a result ‘we can never really know what we are doing’. What we do know is that our actions are ‘irreversible’. They cannot be undone even if the consequences ‘prove disastrous’. If that was the case before the dawn of the internet, how much more is it today?

What Arendt said next is even more important: ‘Only one tool exists to ameliorate the irreversibility of our actions. That is the faculty of forgiving. Without being forgiven, released from the consequences of what we have done, our capacity to act would, as it were, be confined to one single deed from which we could never recover; we would remain the victim of its consequences for ever, not unlike the sorcerer’s apprentice who lacked the magic formula to break the spell.’ It is a crucial insight, but it also seems to me that there has never been a time when it has been more necessary to ponder. In a religious society – as ours used to be and still is in parts – the mechanisms of forgiveness were relatively clear. People could seek it from God. And even those who were not especially devout respected someone who had visibly atoned. Not for nothing was the old PR advice to ‘apologise and move on’.

But the world today can watch someone apologise and yet it can doggedly refuse to move on. In fact, the apology tends to make things worse. Most people who have gone through the process of being hounded relate that the effects on their life are catastrophic. Many say they have ended up contemplating suicide.

It’s no wonder they do, because we live in a society that spends a great deal of energy working out how to bring people down. While our mechanisms for condemning have never been more readily to hand, is anyone thinking about the only tools to counter that? The mechanisms of forgiveness.

If there is, I have yet to hear about it. Our church leaders spend much of their time talking about current shibboleths instead of preaching the actual gospel, let alone presenting perhaps the most extraordinary and truly revolutionary aspect of the Christian message – the commandment to not just forgive but also to love your enemies.

That great release valve that the world once had has been stopped up for years now, if not decades. In its place is a culture which can destroy but not create, tear down but not build up. We cannot seem to find a way out of this trap.

I sympathise with the generation coming up. Of course they are hypersensitive and – as Jonathan Haidt’s work has shown – hyper-cautious. The cost of acting in the world has never been higher. You only have to put one step wrong to be wrong for ever.

Forgiving people only when they happen to agree with you or when it is politically advantageous cannot be the answer. Nor, in practical terms, is the answer immediately obvious. The only thing that is clear is if our culture wants to escape the situation of the apprentice without the spell, we might spend this Easter thinking of the story and the teachings that gave our culture its breath. And wonder whether that breath mightn’t find a way to breathe through us once again.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in