Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life is a historical drama based on the true story of Franz Jäggerstätter, an Austrian who refused to fight for the Nazis in the second world war and was later beatified by the Catholic church. It isn’t peak Malick as it’s linear rather than associative — let’s not pretend we aren’t mightily relieved — but otherwise it’s business as usual in the sense that it’s visually beautiful, poetic, philosophical, theological and slowly, slowly, slowly meditative. In fact, it’s so slowly, slowly, slowly meditative it’s one of those films that feels as if it’s been playing for ever when there is still an hour to go. As such, you may even be moved to ask some philosophical questions yourself — how can this be? — and do your own praying, as in: dear God, is this ever going to end?

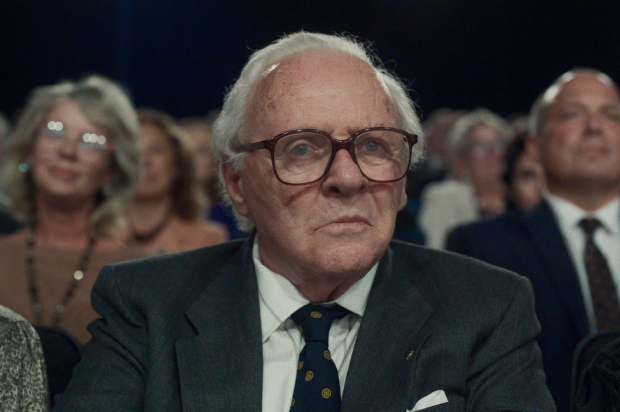

The film does have a certain cumulative power and isn’t a total waste of three hours (or two hours plus another yet to go, amazingly). But it is long-winded and meandering. It opens in the Austrian countryside in 1939 and, of course, the splendour of the landscape is evoked. The mountains. The streams. The apple trees. The golden wheat fields. The chirping birds. The mountains again. (And again! And again!) Nature always takes centre stage in Malick’s films, with humans tentatively edging their way in, and here the humans are Franz (August Diehl) and his wife Fani (Valerie Pachner). The pair, who speak English to each other, inexplicably, are based in a small, tight-knit village where they work their land and live a simple life — that said, her wardrobe would cost a bomb at Toast today — and are happy.

They are young and in love, always frolicking amid the hay, and soon they are joined by three little daughters. However, storm clouds are gathering, literally — we see them rolling across the sky — and then there are planes overhead and Franz is called up for military training. He is separated from his beloved wife and children for months but allowed to return when France surrenders for another period of bucolic bliss and hay-frolicking, before being called up again, this time to fight. But Franz refuses to swear the necessary oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler — ‘I have this feeling inside me that I can’t do what I believe is wrong’ — and is imprisoned.

The pair, who are devout, write letters to each other, which are read aloud in voice-overs. The letters aren’t that interesting and may, alas, even be trite. ‘No evil can happen to a good man,’ Fani may write. ‘How simple life was… what’s happened to our country?’ he writes. He is brutalised in prison as Fani is increasingly ostracised by the village — apart from the odd visit to a bishop, that’s the extent of the drama — yet all the while he refuses to budge an inch. That’s faith, I suppose. And the question the film asks is the question Franz asks his own self: is it better to suffer injustice than hand it out? Plus there’s the local priest who tells him: ‘God doesn’t care what you say, only what’s in your heart. Say the oath and think what you like.’ Say the oath! Say the oath! Say the oath! Then we can all go home! Nope, we’re here for that further hour.

As with most of Malick’s work, from Days of Heaven through to The Tree of Life, the characters are at a remove, which means we don’t feel much for them, and you wonder if he feels much for them either. Here, he does seem much more interested in the mountains (again!) and also the way the light streams through a window or streams through the slats in a cowshed or streams through prison bars. There is even a scene that has us looking up from the bottom of a well to the disc of sunlight at the top, even though the well serves no narrative purpose whatsoever.

Dear God, you may also find yourself praying, enough with the light already. It does have a certain hypnotic, cumulative power — it may just be all those mountains — if you can stick with it. But there is no guarantee that you will be able to.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in