As newlyweds in our late twenties, my husband and I decided to move from a crime-ridden (if trendy) London postcode to a picture-postcard village within commuting distance of the capital. We bought a rather run-down cottage which we imagined would be the perfect canvas for our aspirations: island benches, plantation shutters and lashings of Farrow & Ball. We’d get the house done and have some babies. There would be country dog walks, veg patches and village fêtes. What bliss.

Before we moved in, we chatted to a friendly elderly man in the village. ‘Oh there’s been lots of change in the village lately,’ he told us. Like what? ‘People moving in, people moving out…’ How funny, we thought, that a few new residents counts as radical change. In retrospect, it should have been a warning sign.

Things started off well. We subjected our neighbours to a charm offensive: homemade cakes, wine, cards, invitations to dinner. We signed up to help with church activities, made food for local events, and donated a fancy bottle of champagne to the village raffle. ‘It’s so nice,’ I told my London friends piously. ‘Such a sense of community.’

But then came the fence. When we moved in, our garden was surrounded by a mostly dead, mostly brown hedge with a big hole in the middle. So down came the grotty conifers, and up went a smart new fence. A few days into the work, the man in charge of building it told us that he’d been harangued by some passing locals. We were a bit shocked by that, but he shrugged. ‘Pretty typical in places like this,’ he said.

At the church AGM, we found out what he meant. Everyone knew that we were ‘the people with the fence’. Some villagers were perfectly nice about it; others were eye-wateringly rude. The fence was ‘stark’. ‘I very much hope it softens,’ said another neighbour. The hedge had been a beloved fixture, as it turned out, despite its manky state. Removing it was akin to pissing up the wall of the parish church.

Soon after we found out that someone had called the council to complain about our fence. We eventually worked out that the call had come from the people next door who had initially seemed so nice. More fool us. Soon their friendly greetings stopped and were replaced by glares. Our old London neighbours used to brawl, vomit and shoot up in the street, but at least they weren’t sanctimonious.

There is a secret set of rules in these places that you can only learn the hard way. Occasionally locals will give you pointers. Early on, someone left an aggressive note on our car telling us never to exercise our dog on a small patch of greenery nearby because it was private property. But we had never taken our dog anywhere near this area, so assumed it must have been a warning issued in advance. We discovered that there is a strict hierarchy which is calculated solely by time served. So the lady with a propane bird cannon gets a free pass because she is the longest-standing resident of the village. Never mind that the cannon stops her neighbours from sleeping; she’s been running the village raffle since coronation year.

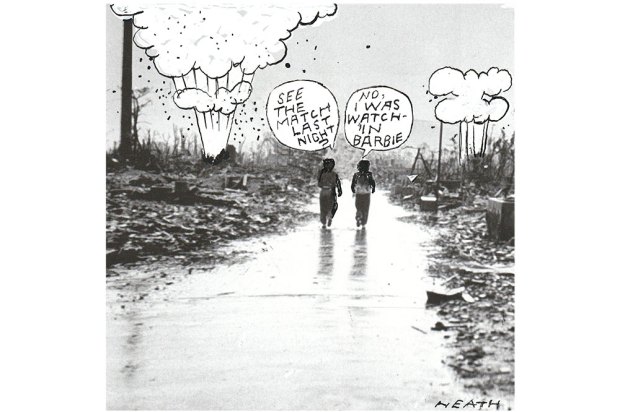

People here really don’t like change, particularly if they’re elderly. It’s perfectly acceptable to allow your house to fall into decay, as long as you don’t change anything. No development goes unprotested, even when it would benefit the local area. A proposed bypass that would hugely reduce traffic through the village is fiercely resisted by locals who might be able to see the new road from the end of their orchards. They don’t seem to realise that opposition to all forms of change only makes it more likely that the worst forms of change will win out. Driving through the area, you frequently come across the remnants of traditional villages, now swallowed up by urban sprawl, but efforts to resist the onward march of developers fail because the council have learnt to disregard the views of people who are fundamentally unreasonable.

It’s no surprise that English villages are in terminal decline. Post offices, village halls, GP surgeries, shops, petrol stations and pubs have suffered from widespread closures, with rural schools particularly hard hit. Liberal Democrat MP Matthew Taylor, author of a National Housing Federation report on rural living, points out that villages are increasingly becoming ‘ghettos of the very rich and the elderly’, and if current trends continue, almost half of rural households will be over the age of 65 by 2039. If there are no working-age adults to run the local village services, then those services cease to exist; and when there are no village services, working-age adults are reluctant to move to an area.

All of this creates a hostile environment for the sort of young people who might bring fresh blood to the community, invest money into the village, and help in efforts to preserve the environment. It was once common for people to live in places like this from young adulthood through to old age, building strong ties to the local area. But villages that once would have been made up of the full range of age groups look increasingly like retirement communities. Reactionary residents seem incapable of recognising that their behaviour doesn’t protect the village, but rather hastens its end.

Six months after we moved in, we found out that our next-door neighbour had been furtively coordinating a campaign to encourage other neighbours to make complaints to the council about our new fence. At that point we decided we’d had enough and moved back to London. Last week, Rory Sutherland suggested that no one ever does this. We did, because a long commute is only worth it if coming home is a joy, and the toxic culture we discovered in our village made life there far from joyful. Our house is now a holiday cottage, which we rent out to the sort of young urban people who fantasise about rural life but are wise enough not to try it full-time. They are delighted by the chocolate box village and quirky décor — and have no idea how dysfunctional the community really is.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in