Anne de Courcy, an escapee from tabloid journalism, has become a polished historian of British high society in the 20th century. Her book The Viceroy’s Daughters, an account of the three daughters of Lord Curzon, marked her transition from debutante-itis to something grittier. It was followed by a biography of Diana Mosley, published a few months after Mosley’s death. When I questioned Diana about it she told me that her previous biographer, Jan Dalley, had been frightened to ask anything too personal, but that De Courcy had been robust and unafraid to probe.

That fearlessness was most in evidence in De Courcy’s biography of Lord Snowdon, published in 2008, which in its way was as much of a breakthrough as Michael Holroyd’s life of Lytton Strachey had been in the 1960s. The latter was the first serious biography to incorporate details of a subject’s erotic life. De Courcy’s Snowdon did this with the earl’s approval and was published while he was still alive. Since Snowdon emerges in a bad light, how did De Courcy get him to co-operate? My guess is that they came to an understanding: she would avoid the gay stuff, if he would allow the straight stuff; but I don’t know, and it is still astonishing to read.

My expectations, therefore, of Chanel’s Riviera were high. But the book is weirdly out of focus from the beginning. There is a short introduction, followed by a short prologue, which more or less repeats what the introduction says. The text proper opens with an account of Chanel’s affair with Bendor Westminster — which took place in the 1920s and ended in 1930, the year this book supposedly begins. Chanel is described as ‘beautiful, elegant, witty and fiercely independent’. She wasn’t beautiful, but she was smart. And Bendor is ‘tall, blond and good-looking’. He wasn’t blond but, yes, he was good-looking. As for the Riviera, it is repeatedly characterised with similar lists of film-treatment platitudes: ‘That era of bias-cut satin evening dresses, Hollywood films, beach pyjamas, exotic cocktails, harbours crammed with yachts and super-stylish motor cars. ’

Chanel’s Paris — yes, of course. But Chanel’s Riviera? She built a villa, La Pausa, at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. Its architecture is a forbidding but striking adaptation of Provençal style, and she filled the place with brown furniture from Bendor’s attics. She usually went there to hide with a raffish lover, would sometimes admit close friends such as Misia Sert or Jean Cocteau and occasionally gave a big-name dinner party. Once you’ve added her invention of suntan and those beach pyjamas, that’s it. Chanel was a loner and had no set. The Riviera action was elsewhere.

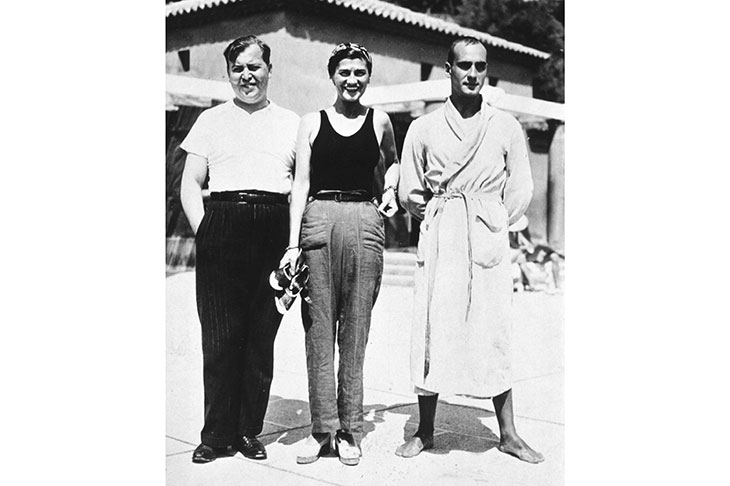

De Courcy’s task has not been made easier by this being the third book about the Riviera in peace and war in the past three years. She gallantly sews in Chanel pieces where she can, but there’s not enough to justify the title. For the necessary wads of padding she reverts to what she knows best, so here come the usual characters from the Anglosphere: Edith Wharton, Aldous Huxley, Somerset Maugham, the Furnesses, Churchill, Maxine Elliott and H.G. Wells; even Brian Howard and Cyril Connolly (who would have been surprised to read that he ‘had no financial need to write’ — he was broke all his life). And do we really want another lengthy dish-up of the abdication crisis and those quintessential airheads, the Windsors?

Once war is declared, the tenor of the book alters — it is more vox pop — and we are in the nightmare world of Jewish round-ups, mass shootings, hunger, collaboration and Resistance. The less familiar testimonies are very moving; but there is too much general history and too little that is Riviera-specific. (If you want a spellbinding evocation of the Riviera in wartime I recommend Patrick Modiano’s Honeymoon.)

Chanel’s collaboration with the Nazis is a subject in itself (she was vociferously anti-Jewish and lived at the Ritz with a German officer), but De Courcy trivialises this. We hear that Chanel needed a man in her bed and that her allegiance was always to herself. In fact she lived for many years after the war in moral disgrace in Switzerland, and is buried there. The liberation of the Côte d’Azur, an obvious climax, is almost thrown away.

One final bewilderment in this book of bits: the colour photograph of Chanel’s villa bears no resemblance to the Villa La Pausa I was taken to. Unless I’ve gone ga-ga, they’ve put in the wrong photograph.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in