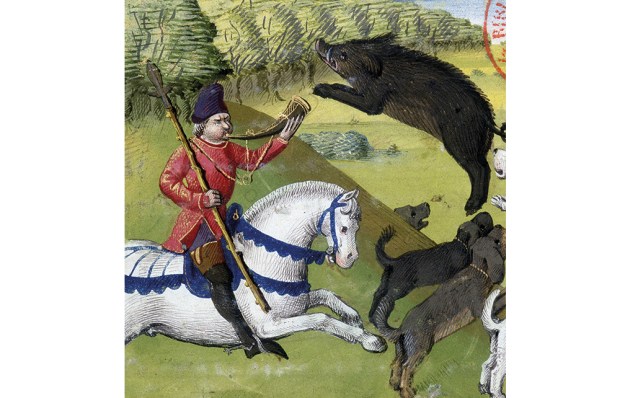

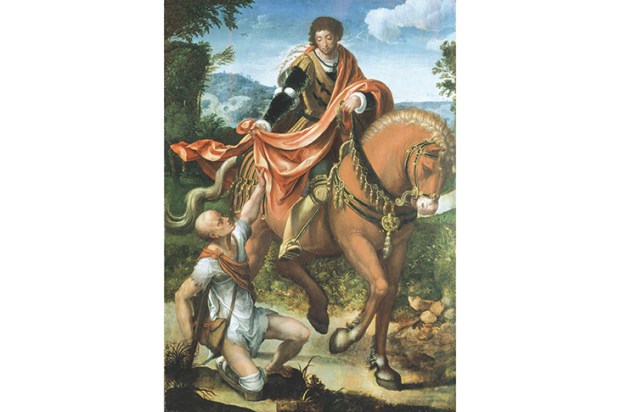

The crusades are part of everyone’s mental image of the Middle Ages. They extended, in one form or another, from the 11th to the 16th century. Those which reached the Holy Land were fought by men on horseback wearing metal armour and carrying lances and swords, as in the pictures. The onset of gunpowder had not yet spoiled the fun. They were truly international, in their own way emblematic of the myth of a single Christian European polity. They embodied everything that people associate with medieval warfare: reckless courage, murder, loot, adventure and romance.

Christopher Tyerman has been writing about the crusades for nearly 40 years. His work includes the only full-scale study of English crusaders and God’s War, which for my money is the best one-volume history in print. This is quite an achievement, for there is a finite body of material, which is unlikely to expand significantly, and consists mainly of published chronicles. Many people picking up Tyerman’s latest volume may be tempted to think that it simply recycles the material in his last one. They would be mistaken. The World of the Crusades has a mass of new insights, many little-known anecdotes and a fresh approach to the subject which fully justifies its bulk.

Two features of the book are particularly striking. First, instead of just treating the crusades in the standard way as a European Christian movement, Tyerman has placed them in their proper geographical setting, as incidents in the history of the Islamic Middle East. By a fortunate accident, the early crusaders hit the Levant at a time of ferment and instability in the Islamic world. The Abbasid caliphate, essentially a Persian regime based in what is now Iraq, had been in terminal decline for two centuries when the first crusade arrived. The rival Fatimid caliphate of Cairo, which was the dominant power in the Arabs’ lands and among the Berbers of North Africa, had passed its apogee and been supplanted in much of its territory by unstable local dynasties.

Into this collapsing world came successive waves of nomadic invaders from the east: Seljuk Turks, Ottoman Turks and finally Mongols. Tyerman traces the ebb and flow of their fortunes and the disruption of the Middle East which gave the crusaders the opportunity to establish themselves in the region. The crusader states in the Levant lasted for barely a century before Saladin briefly united the western Islamic world against them and expelled them from all but a few coastal enclaves on the Mediterranean and some powerful inland castles of the Knights Templar.

Tyerman’s second innovation is to insert into his text every few pages a free-standing mini-essay on some aspect of crusading which would otherwise be overlooked in the narrative sweep. These interesting amuse-bouches placed between the heavier soup, fish, meat and dessert courses cover such matters as the place of women on crusades, holy hirsuteness, diet and cuisine, the use of interpreters, tombs and monuments, Levantine decorated manuscripts, crusading architecture, baggage trains, military medicine and many other marginal but fascinating topics which enrich the narrative and justify the author’s claim to have presented not just a succession of brutal wars but another cultural world.

The crusades have an unsavoury reputation among right-thinking people. Wars of religion have not been quite the thing since the 17th century. The received opinion about the crusades has remained remarkably constant. Except in 19th- and early 20th-century France, where they were regarded as part of the nation’s mission to civilise the rest of the world, assessments have been uniformly negative. David Hume famously called them ‘the most signal and durable monument of human folly that has yet appeared in any age or nation’. Gibbon, Voltaire, Walter Scott and professional scholars right up to Steven Runciman and beyond agreed that they were an ugly, philistine, violent, greedy and fanatical blot on Europe’s escutcheon and a damaging diversion of effort and wealth into a doomed endeavour. In March 2000, Pope John Paul II was moved to apologise to the modern world for the fact that they had ever happened.

The public’s taste for the subject has, however, been entirely unaffected by these worthy attitudes. It is easy to see why. It is precisely because a durable conquest of the Middle East by western Christian adventurers was such a quixotic and unrealistic objective and the human cost of the attempt was so high. Heroism in a hopeless cause has always been attractive, in history as in fiction. It is richly absurd today to condemn the Middle Ages for having different values from our own. But human heroism is a constant of every age, and the reading public will always find it compelling. They have a point.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in