Why do people collect? Cicero said of the Roman governor of Sicily Gaius Verres that his appetite for Greek sculpture was called a passion by himself but a mental illness by his friends. Freud attributed the collector’s mania to bad toilet training. Others claim to have proved that it is due to abnormalities in the medial prefrontal cortex. Psychologists have filled thousands of pages on the subject in peer-reviewed journals. It is safe to assume that Christopher de Hamel has not read any of them. But in this fascinating book he presents 12 case studies of men and women with just one thing in common. They were all obsessed with acquiring, selling, making or in one case forging medieval manuscripts.

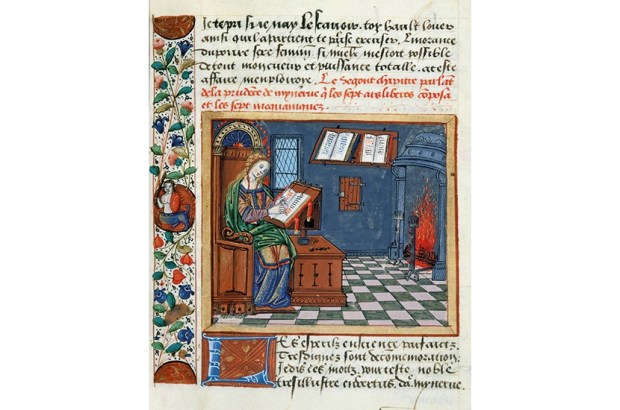

Books and manuscripts have probably been collectors’ items for longer than any other class of objects. They are coveted for different reasons. Most early collectors acquired books for the information conveyed by the text. De Hamel’s first case study, the 11th-century Benedictine monk Anselm of Bec, was a bibliophile in this classic mould. He wanted to read them. The 15th-century Florentine bookseller Vespasiano da Bisticci sold classical Latin literature according to canonical texts already in general circulation. His customers wanted to read them. The 17th-century antiquary Sir Robert Cotton’s chief motive was to save materials for English history from destruction by ignorance, damp and rats. The 19th-century Greek forger Constantine Simonides, who deceived many collectors in England and Germany, catered for tastes like these. Perceiving the demand for great scholarly breakthroughs in biblical studies, he invented the necessary texts.

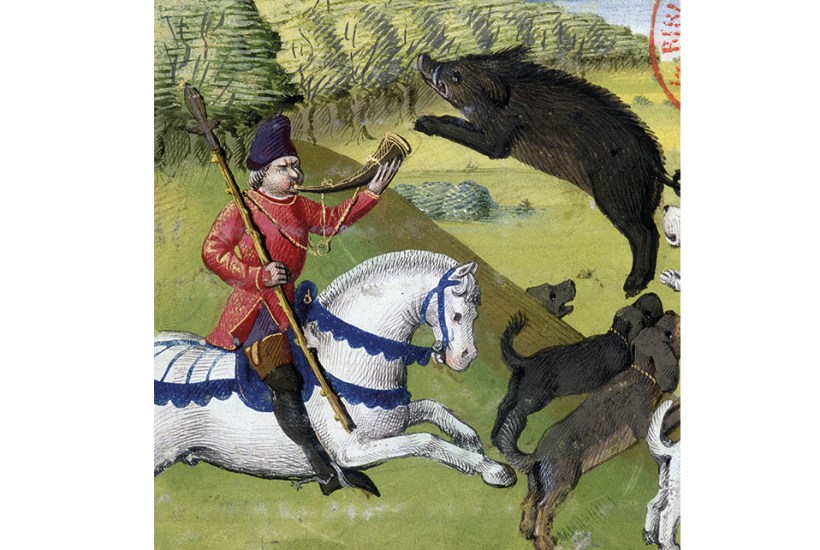

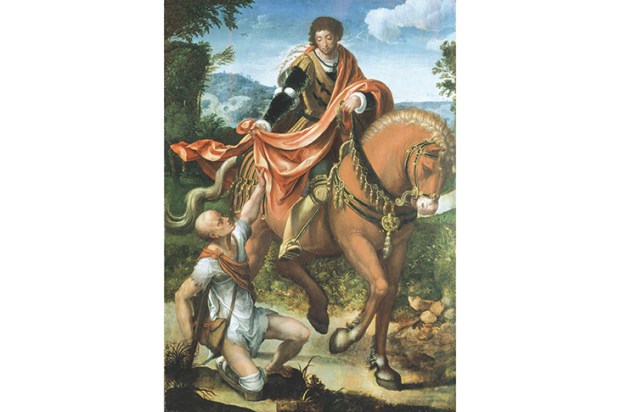

For centuries, however, medieval manuscripts have been prized chiefly as artistic objects, not as textual authorities. They are desired for the beauty of the script, for their pictorial decoration and sometimes for their luxurious bindings. The 14th-century Duke of Berry, brother and uncle of successive kings of France, is De Hamel’s second case study. He was one of the earliest collectors of manuscripts as artefacts, most of which he commissioned himself from the great artists of contemporary Paris. The Très Riches Heures in the museum at Chantilly, a Book of Hours in which the man himself and his many homes are shown in beautiful full-page illustrations, is arguably the most famous illuminated manuscript in the world. Even austere librarians, whose main concern was to collect materials for scholarship, were tempted by the gorgeous creations of medieval illuminators. Cotton acquired some of the most beautiful decorated Anglo-Saxon manuscripts now surviving, including the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Vespasian Psalter. The grim Victorian keeper of manuscripts at the British Museum, Sir Frederick Madden, bought the Bedford Hours for the museum, one of the last productions of the great Parisian school of illuminators, parts of which were commissioned by the Duke of Bedford (d.1435) when he was the English regent in a conquered city.

It was the financial and industrial millionaires of the 19th and 20th centuries who brought manuscript collecting to its highest pitch of competitive ferocity. They were aggressive collectors, latter-day dukes of Berry with almost unlimited means. The American railroad magnate Henry E. Huntingdon bought the Bridgewater Library of the Earls of Ellesmere, including the famous Ellesmere Chaucer, for a cool million dollars in 1917, then the largest sum ever paid for a single collection.

The New York banker J. Pierpont Morgan created the finest collection of medieval manuscripts in the world outside the great European state collections. It took him only 50 years, when their accumulations had been made over several centuries. The final chapter of De Hamel’s book tells the story of his collection through the eyes of his remarkable librarian, Belle de Costa Greene. She was a black woman, the granddaughter of slaves on both sides, who had to disguise her origins behind a paleish skin and a bogus Portuguese name to survive in a male-dominated, segregationist America.

The last person to assemble a collection of international renown was probably the English brewing millionaire Major J.R. Abbey, who created a remarkable collection of Italian Renaissance manuscripts after the second world war. The achievement would now be difficult to repeat, for there are so few outstanding examples still in private hands. De Hamel himself, who worked in the western manuscripts department of Sotheby’s for a quarter of a century, was instrumental in selling some of the last great pieces to appear on the market. It is interesting to speculate on what will now happen to a field of connoisseurship concerned with objects that are almost all in public collections but are too sensitive to light and breath to be displayed there. Manuscripts were made for the private enjoyment of collectors and their friends.

It is one of the strengths of De Hamel’s writing that he draws us into this enclosed world, mining a reach seam of knowledge about manuscripts and their creators and owners. His Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, published six years ago, was an unexpected bestseller that won a clutch of literary awards and introduced this hitherto arcane branch of art history to a wide audience of non-specialist readers.

The appearance of The Posthumous Papers of the Manuscripts Club shows that the seam is not yet exhausted. Readers of the earlier book will recognise the idiosyncratic style. De Hamel does not lecture us from on high. He does not start from the beginning and work through to the end. He does not lay out his facts in an orderly queue waiting for our attention. He writes like a genial uncle or an engaging raconteur after a good meal. He is discursive, turning aside to discuss fresh themes as the thought occurs to him. He imagines himself chatting to the likes of St Anselm or Sir Frederick Madden, and invites us to join him, even telling us how to find the right house or room (‘up the stairs, and along the corridor’, etc). The result is an eccentric but charming and instructive book which is oddly difficult to put down.

The post The collectors’ obsession with rare medieval manuscripts appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in