‘Can I get you a cup of tea?’ asked the lady as she sat beside me in the caravan. The old farmer, a horse dealer, sat on another seat looking stunned.

‘You look exhausted,’ she said. I was. I’d driven hundreds of miles looking for horses I had seen seized from the horse dealer’s farm. But I didn’t want to worry her by telling her where I thought I had found them.

I had set off in pursuit of a fleet of lorries marked with the address of a Yorkshire company, after 123 horses were seized by the RSPCA and the police in a joint operation with Trading Standards, from Hurst Farm, just down the road from my house in Surrey. Although the place was always a mess, I felt uneasy. Having driven by every day and always seen the horses eating from plentiful bales of haylage in winter, or grazing 100 acres of grass in summer, I was doubtful that these horses needed rescuing.

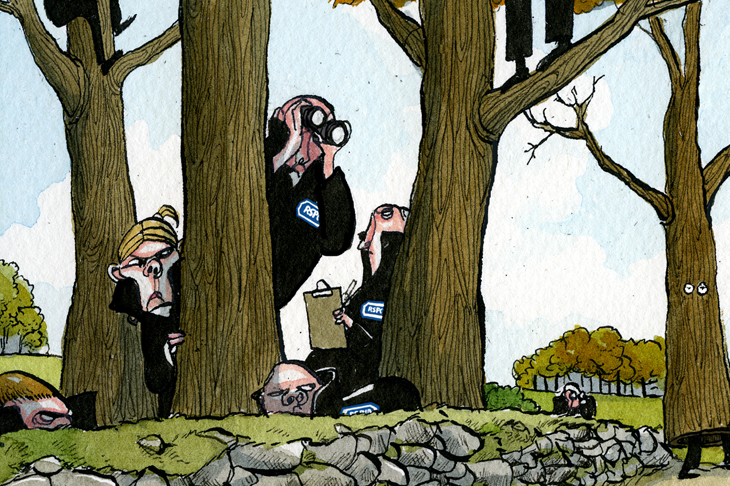

The RSPCA told local people not to worry about the horses — they were going to nearby shelters. But the lorries had come down from Yorkshire, so the journey had to be a long one or it didn’t make any sense.

My bitter experience of investigating past horse seizures made me get in my car and set out to find them. I drove and drove, until finally I think I found some of the horses in a barn on a farm, somewhere remote.

As I was looking, independent vets charged with visiting seized horses were engaged in an 800-mile round trip to view them all and verify their condition. They found that they had been transported almost to the four corners of the country, from south to north, Wales to East Anglia.

Meanwhile, the RSPCA admitted publicly that seven horses had already been PTS (put to sleep) — two on site during the raid, and five more in RSPCA care. They insisted this was on the advice of vets.

For some time now I’ve been looking into RSPCA horse seizures. Through my various investigations I have built my own contacts with animal welfare staff who’ve been able to help me with this case. And from documents they’ve shown me, I could see that some foals had been judged to be in ‘poor body condition’ because they did not have enough muscle. Young horses don’t grow muscle until after they grow bone. There was also paperwork showing that the horses had been judged very poorly because of red worm, which ought to be treatable.

Some of the photographs I saw of young horses were supposedly of the ‘poorest’ ones. All I can say is that if the RSPCA puts them down, I am going to be heartbroken, because they look to me to be in a perfectly reasonable condition for winter: furry and roughed up by weather, but by no means at death’s door.

‘You mean you’ve been looking for them?’ said the lady. I nodded. ‘Where are they?’ she said, both her face and his suddenly lit up. I nearly burst into tears.

No charges have been brought, and the investigation is said to be ongoing — in consequence of which the RSPCA refused to answer the detailed questions I put to them about the case.

But while the farmer is refusing to sign his horses over to the ownership of the RSPCA, he is being charged £13.50 a day per horse, and that’s £1,660 a day for the herd — which he has been warned will be between £750,000 to £1 million by the time of any trial. The RSPCA say this is the cost of the horses’ livery. But the word livery is sometimes to be used loosely.

What I found while looking for horses in unofficial holding centres used by the RSPCA were windswept, bleak fields where horses in past seizures have stood up to their knees in mud.

I came home exhausted, with a dose of food poisoning and full of the same hopelessness that nearly did for me the last time I tried to investigate the RSPCA.

The truth of Britain’s animal rescuing industry is unutterably awful. When you start looking into where all these seized animals go, you begin to question everything you think you know.

It was on return from my travels that I went to see the horse dealer. What he and his lady companion told me about what happened was this: it was a dawn raid; they were detained in the caravan while the farm was searched and all the dogs and horses seized; two sick horses recuperating on straw beds in the barn were put down as they lay there. As the farmer talked, I realised that he wasn’t quite looking at me.

One of the main complaints about his farm, leading to calls over the years by locals to the RSPCA, was that the haylage bales were messily arranged with the wrappers not taken off properly so the plastic lay on the ground. Several broken hay holders were not disposed of either, and lay wonkily in a ditch.

The old boy told me of his daily routine, taking four to five round bales each morning out to the herd, at a cost of many hundreds of pounds a week. His hay supplier confirmed this. He also had hard feed piled up and a bill as long as your arm from the local feed merchants.

He made several embarrassed comments about the mess before I said: ‘Have you told your lawyer you are partially sighted?’

He looked downcast. ‘Not really,’ he said hesitantly. Even though the horses had plentiful hay, he couldn’t see properly to clear up, is my guess.

It is the same with almost every case. Once you scratch the surface of animal conditions, the human condition behind them is revealed. As I made my way home, I kept asking myself: how is this allowed to happen in a nice Surrey village? Actually, I think it happens especially easily in a nice village, where a lot of people these days hate mud and messy fields full of gypsy cobs.

As the countryside disappears, it makes way for chocolate-box villages with cafés and manicured greens. NO HORSE RIDING says the sign on our green. Few local residents want to look at the reality of farming or livestock.

There are, though, plenty of people who know nothing about animals who will call in and report muddy horses in winter. And that is all you need if you want to get public support to raid a messy old horse dealership standing on land worth millions.

The RSPCA gave an interview about Hurst Farm saying that the raid showed they faced a winter horse crisis. I suppose that might boost donations from concerned supporters. And they will hope to recoup six–figure costs, if that is what they say they have run up, if and when the farmer is put on trial.

By that time a new housing development may be emerging around those muddy fields. Plans had been lodged a day before the raid at Guildford Borough Council for six luxury homes, to be built at the front of the land, exactly where the horses had been eating their hay. A spokeswoman for the RSPCA said the charity had no idea when it carried out the raid that plans for a housing estate were being put in.

‘These animals came into our care because vets had welfare concerns for them,’ she said. ‘Very sadly, five of the horses at independent equine veterinary hospitals, or being cared for by our partner charities, have since been put to sleep. These decisions were not taken lightly and were on the advice of vets for medical reasons.’

For those who devoutly believe in the RSPCA — and there are many — the ultimate proof of their good intentions will be to see the remainder of the rescued horses in better conditions than they were in before.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in