I suspect that whether or not you admire Neil MacGregor’s latest series for Radio 4, As Others See Us (produced by Paul Kobrak and Tom Alban), will depend on how you feel about Brexit. To my ears, it was shamelessly in favour of a Britain that stays in Europe and remains committed to its global role as the voice of moderation, a disseminator of liberal values, unusual in its ability to draw in other influences while retaining a strong sense of its own identity — and therefore to be cheered and recommended as essential listening. MacGregor is doing everything within his power to show us what we need to hear, before it’s too late, in these five intense and impassioned programmes.

He set off across the globe in search of an answer to that question ‘how do others see us?’, choosing Germany, Egypt, Nigeria, Canada and India as representative of widely differing connections to the United Kingdom, former enemies, subjects, compatriots. He wants us to know what others are taught about Britain in school, what they believe to be most important about us, which objects, events or persons are most representative of the British character or place in the world.

In Germany he was surprised to discover how much affection there is for Britain, beginning with that weird New Year’s Eve tradition beloved of Germans: the annual screening on TV of the black-and-white sketch, Dinner for One. In that absurd slapstick comedy (made in English by German TV in 1963 and starring Freddie Frinton and May Warden) many Germans see the quintessential British characteristics of nostalgia, class, faded grandeur, but perhaps above all an ability to poke fun at ourselves.

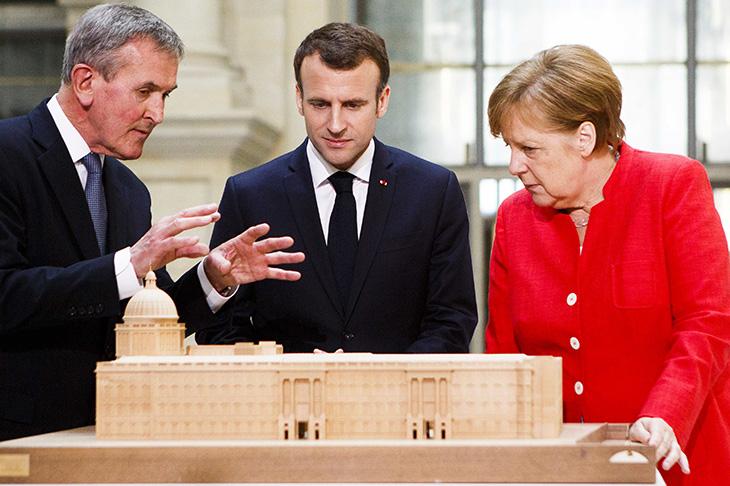

Hartmut Dorgerloh, director of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin (where MacGregor is founding director), grew up in communist East Germany in the 1960s and told us how he travelled to Britain in his imagination through listening to BBC radio. He was always fascinated by Britain’s ‘double face’, the dark side of its imperial history and on the other side its catalogue of great artists, inventors and explorers; the greedy capitalism that made it ‘great’ and the open friendliness he found in the B&Bs he visited in the 1990s as soon as he was free to travel. ‘It was a good way to see British interiors,’ he recalls now, astonished by the ‘wall-to-wall carpets in pink in the bathroom’.

Shakespeare was mentioned a lot in these conversations, the Beatles, cricket, the NHS and Margaret Thatcher. In Canada, MacGregor spoke to the novelist Madeleine Thien, who grew up in Vancouver with parents of Chinese descent. There was something compelling about what she said, in spite of or perhaps because of her gentle, softly spoken voice, nothing polemical about her tone. On the contrary, she appeared to invite us in to her understanding of what’s been going on in the UK and how its place in the world has been changing ever since, she believes, the second Iraq war. Once open to change, to foreign influences, to other peoples, Britain is no longer taking that stance, and is no longer seen as such by others. It could still, she believes, be the country that safeguards and promotes civil institutions, advocating a politics that includes everybody and stands for certain values, but, she added after a long pause: ‘I don’t get the sense it wants that role any more.’

Working with ever-diminishing resources, the controller of Radio 4, Gwyneth Williams, is valiantly focusing on what the network does best — taking us inside different places, showing us alternative views, and making us think. This week’s must-listen was Mark Tully’s edition of Something Understood for Epiphany (produced by Frank Stirling). Sadly, there will soon be no more new editions of this stalwart of the weekend schedule, surprising often in its approach, always thoughtful and above all wide-ranging in its gathering of ideas and beliefs, in just half an hour helping us to rethink, rebalance our entrenched opinions. It’s hard to see how much money cutting this programme will save since its main expense is thinking time. But it’s probably something to do with the fact that it already has a rich archive (23 years’ worth of weekly programmes) that can fill up the ‘beliefs’ slot on BBC Sounds. It will still be heard on the network; it’s just that they will be repeats rather than programmes made in and of the moment.

On Sunday, recognising like MacGregor that now is a time to work out what makes us tick, what we need to treasure before we lose it for ever, Tully focused on one aspect of the Epiphany story, the good news of Christ’s birth, which should, according to St Paul, bring us joy, make us happy. But what is it to be happy and how do we attain happiness? For the Dalai Lama, in whom happiness exudes from every pore, it’s about training the mind, an inner discipline, the transformation of attitude. ‘You need courage to find happiness,’ says Tully, tuning in to Ella Fitzgerald and her song ‘Get Happy’. After all, you have to be prepared to stand up and speak out for happiness, get ready for the Judgment Day.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in