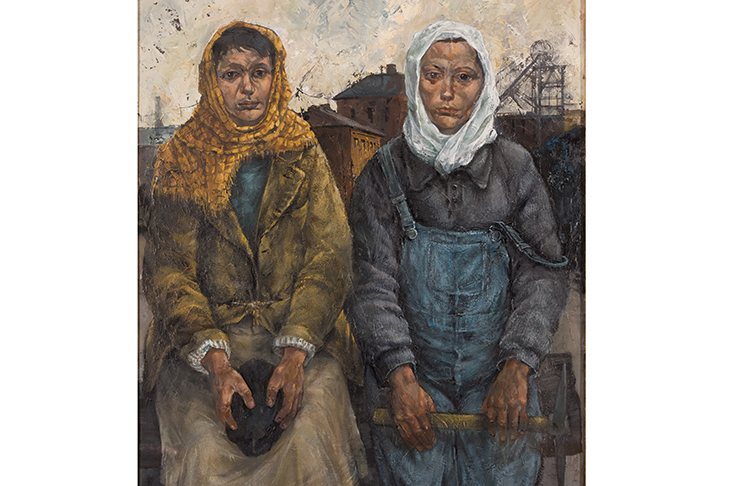

‘They did not look like women, or at least a stranger new to the district might easily have been misled by their appearance, as they stood together in a group, by the pit’s mouth.’ As opening sentences go this is a cracker, but few modern readers of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s That Lass O’Lowrie’s get far beyond it because the novel’s characters speak in a Lancashire dialect that makes Mark Twain’s Huck Finn sound like a Harvard preppy.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in