Some disasters could not occur in this age of instant communication. The first world war is a case in point: 9.7 million soldiers died, 19,240 British on 1 July, 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, alone. If all that had been seen on social mediaand rolling news threads, public opinion would have shifted immediately.

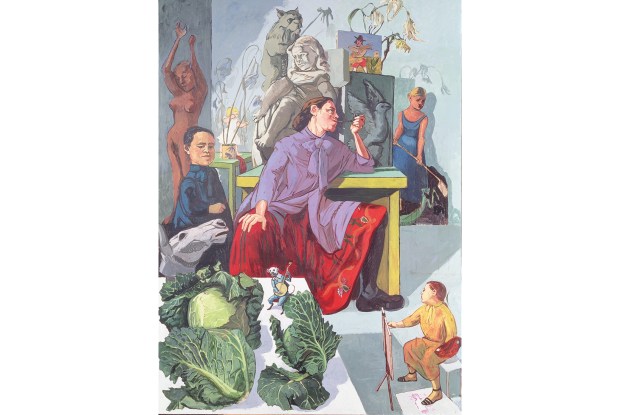

A hundred years ago, however, the sheer awfulness of what was happening took more time to sink in. Aftermath, an exhibition at Tate Britain, deals not so much with the art of the war itself as with the shocked and grieving era that followed the cataclysmic conflict: post-war art.

The horrors of the fighting continued to haunt artists on all sides, but not with equal force in every combatant country. In Britain the images were more softly elegiac than across the Channel. There was little appetite for even muted dreadfulness. The story of William Orpen’s ‘To The Unknown British Soldier In France’ (1921–28) is revealing in that regard.

Orpen was commissioned by the Imperial War Museum to paint three pictures of the Paris Peace Conference. But the painter, who had seen the battlefield of the Somme as a war artist, was outraged by the way the dead and wounded seemed forgotten by the assembled diplomats. ‘Why upset themselves and their pleasures by remembering the little upturned hands on the duckboards, or the bodies lying in the water in the shell-holes?’

So, after completing two group portraits of the delegates, on the third canvas he painted a coffin, draped in the Union Jack, standing in the grand halls of Versailles, and flanked — originally — by the almost naked wraiths of two dead soldiers. When this was exhibited at the RA, Orpen was vilified for ‘bad taste’, sacrilege even, and the Imperial War Museum refused to accept the picture. Eventually, the artist decided to remove those spectral figures.

In retrospect it is striking how mild Orpen’s protest was — even in the unmodified version. Indeed, that was generally true of British war art. Similarly C.R.W. Nevinson’s ‘Paths of Glory’ (1917) was banned by the military censor, leading him to exhibit it with a piece of brown paper inscribed ‘censored’ over the image, which shows two corpses face down in the mud. But even uncensored, this is a great deal less scarring than many German responses to the carnage.

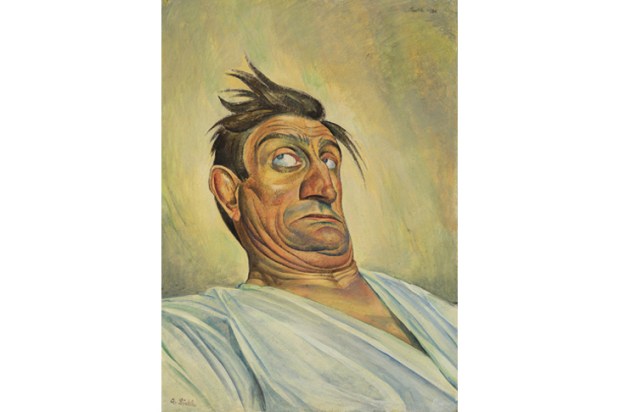

In the work of Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz and George Grosz the rage and grief are extreme. Mutilated survivors, of whom there were many thousands, are seen in full nose-less, eyeless, limbless detail in Beckmann’s series of lithographs aptly entitled ‘Hell’ (1919). True, Henry Tonks — a renowned teacher of drawing and a surgeon — documented similar disfigurements in British hospitals, but his fastidiously precise pastels were intended as scientific records (and were not widely seen until quite recently).

This difference was partly art historical — British artists tended to represent the conflict as a violation of nature, through shattered landscape; Germans saw it in terms of Bosch, Bruegel and the Dance of Death. But it was also because for them the disasters of war were unmitigated even by nominal victory.

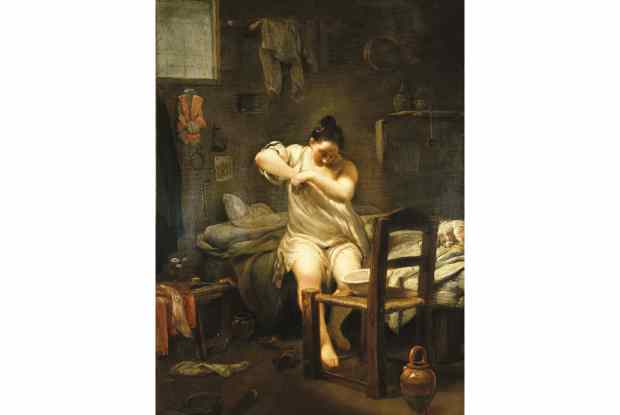

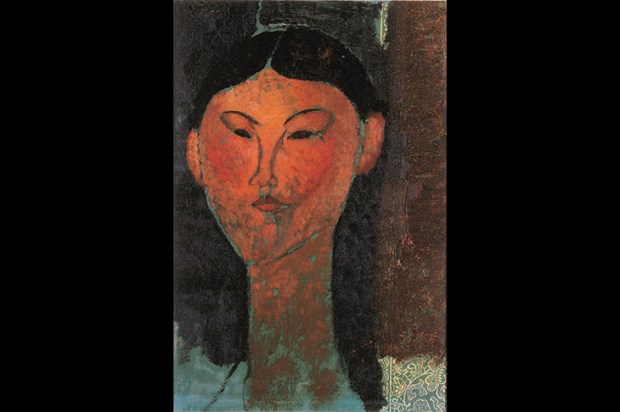

The French response was not so evident in direct depictions of the conflict as in a change of cultural gear. In Paris the full-throttle cubism and fauvism of the pre-war years was replaced by the dreams and nightmares of surrealism — and a classical revival known as the rappel a l’ordre, or return to order.

Various artists — not only French ones — moved with this current. But such affinities do not necessarily mean that pictures by painters as different in visual wattage as Pablo Picasso and Dod Procter will get on together on a gallery wall. The result is that the latter’s modest masterpiece ‘Morning’ (1926) is rather unfairly outshone.

All too often Aftermath is a jumble of the good, the bad and the indifferent. There are some outstanding things on display — by the German sculptor Ernst Barlach, for example. The underrated William Roberts and Edward Burra look strong too, but there are plenty of feeble pieces, such as Albert Birkle’s ‘Cross Shouldering’ (1924), a maudlin exercise in mingling Christian and socialist imagery. That’s the drawback of shows like this, which are fundamentally concerned with history rather than art. Sorrow and pity are no guarantee of artistic success.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in