In 2004 Mexican art historians made a sensational discovery in Frida Kahlo’s bathroom. Inside this space, sealed since the 1950s, was an enormous archive of documents, photographs and personal possessions. This hoard forms the basis of Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up, an exhibition at the V&A.

Oscar Wilde once remarked that ‘one should either be a work of art or wear a work of art’. Kahlo opted for both, and she didn’t stop there. Though she was a Marxist who numbered Trotsky among her many lovers, she also channelled the role of saint and martyr.

She was neater than Francis Bacon, whose studio-floor detritus has also been subjected to zealous forensic analysis — but the clutter Kahlo left behind her was similarly eclectic. Some of the exhibits were required because of her multiple disabilities. Kahlo suffered polio at the age of six followed by a near-fatal bus crash in 1925, which shattered her spine.

On show are the medicaments she took and the plaster corsets she had to wear, and, most poignant of all, a prosthetic limb necessary after Kahlo’s right leg had been amputated towards the end of her life. These pathetic items have the air of religious relics about them, her version of the crown of thorns. Of course, Mexico is an intensely Catholic culture. Kahlo’s ‘Self Portrait as a Tehuan’ (1943) resembles a baroque Madonna. Her tears are those of a mater dolorosa, and poor Frida, who underwent some 30 operations before dying aged 47, certainly had lots of sorrows to suffer. The idea of the artist as holy victim and outsider goes back to the 19th century. Van Gogh and Gauguin were fascinated by it.

In addition to this role, Kahlo emphasised her exotic origins, at least as viewed from the perspective of Europe or the USA. She wowed the gringos of San Francisco on a visit in 1930 dressed in the costume of a Zapotec woman from the province of Oaxaca, and afterwards adopted this outfit as a trademark. There is a gallery filled with the marvellous regional textiles she wore, typically with an Aztec necklace as accessory.

There are, it is true, also quite a few paintings and drawings on display, among them some of Kahlo’s best known. But if the show had been restricted to her pictures, it would have been a small one, whereas this is actually one of the V&A’s more ambitious efforts: rambling on for room after room, accompanied by eerie music.

My first instinct was suspicion. This looks like an attempt to inflate a smallish quantity of loans into something grander. But as I walked round I had second thoughts. The truth is that as a painter — despite her huge fame — Kahlo is not outstandingly interesting. True, she was a lot better than her husband Diego Rivera, who was much more famous during their lifetimes and whose epic political murals now look grandiose, vapid and dated. In contrast, Kahlo had a sharp sense of design and a knack for strong colours that sing together. The limitation of her work was that it is all about her. Although only about a third of her output consists of self-portraits, all of her best-known works are among them.

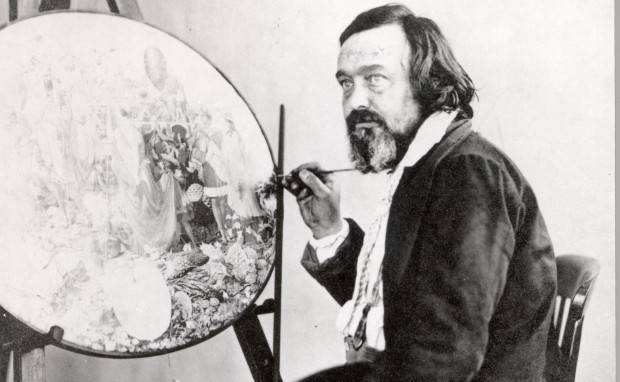

Having said that, certain painters have long made their personal appearance part of their work. Rembrandt did it. Gauguin — in several ways a precedent for Kahlo — painted himself as a Breton fisherman, then later as an Oriental sage, and also as both Christ and the devil.

Kahlo’s remodelling of herself extended to make-up. The catalogue investigates this with a zeal more usually devoted to, say, Rubens’s application of burnt umber. It seems that Kahlo strengthened her celebrated conjoined eyebrows — like a bird taking flight, in Rivera’s opinion — using ‘Ebony’ by Revlon and also a French product, Talika, designed to encourage hair growth. Even more excitingly to contemporary scholars preoccupied with her ‘gendered identity’, rather than plucking her pronounced moustache, she flaunted it.

Does any of this matter? I left the show convinced that in Kahlo’s case the work of art really was herself. The proof is that the photographs and films of her, especially the beautiful colour ones taken by her lover Nickolas Muray (and probably partly conceived and directed by the artist), are just as powerful as the paintings — though the latter dwell more on her suffering and injuries.

Although distinctly over-the-top and containing an excess of bric-à-brac, Making Herself Up succeeds in making Kahlo more comprehensible and intriguing.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in