Every time a friend succeeds, I die a little, so you can imagine how sickened I was by the magisterial TV adaptation of John Preston’s A Very English Scandal (BBC1, Sundays).

I’ve known Preston for years. It’s himI have to thank for the compendious collection of CDs rotting in my attic, from the ten years or so I spent working under him (he was the arts editor) as the Sunday Telegraph’s rock critic. But though I’ve hugely enjoyed all his quirky, low-key, sardonically amused novels — loosely on the theme of ‘quiet desperation is the English way’ —I never imagined he’d luck out quite so spectacularly as he has with this truly splendid all-star production.

Script: Russell T. Davies; direction: Stephen Frears; cast: Alex Jennings, Ben Whishaw and, finally maturing into a proper grown-up character actor rather thana handsome chap who always plays himself, Hugh Grant. Three hour-long episodes too, so plenty of time for the period atmosphere and character detail in which this particular saga is so obscenely rich that if it were fiction you’d accuse the author of overegging it.

And the same goes, of course, for the plot. In what bizarro parallel universe would the popular and upstanding leader of the Liberal party — and likely deputy prime minister in a coalition government — hatch a scheme to have his troublesome male ex-lover bumped off by a hitman so incompetent that all he manages to kill is the Great Dane? And in what equally strange world, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary — some of it in the hands of both the police and MI5 — would the courts find him not guilty?

To anyone under 40 it might seem almost inconceivable that this is real history. But those of us who lived through it — in my case at my prep school, where we got our licit kicks from the lurid court reports they used to have on page three of the Daily Telegraph — it’s as fresh as if it were yesterday: ‘Bunnies can (and will) go to France’; Rinka the luckless dog — subsequently immortalised as the answer in a gazillion pub quizzes; Thorpe looking all shifty and fake-chirpy under his Homburg.

Thorpe is a gift of a role for Grant — by turns charming, devious, funny, clubbable, ruthless, imperturbable, manipulative and burdened with an Olympian sense of entitlement that even Thorpe’s Eton contemporaries found de trop. The latter is exquisitely captured in the scene where he formulates the plan in front of his hopelessly smitten gofer Peter Bessell (a superbly needy, obliging Jennings). It seems genuinely not to occur to Thorpe that murdering someone might be illegal or immoral. Surely any damn fool can see that the national interest — synonymous, of course, with Thorpe’s career success — comes before such pettifogging niceties as the sixth commandment?

Mind you — and this is the beauty of the story — nothing is straightforward. Nobody is wholly sympathetic or reprehensible —you can almost see Thorpe’s point. Norman Scott (né Josiffe), the only main player still with us so we’d better tread tactfully, was not, perhaps, the luckiest choice of pretty boy with whom to have a fling. He harried Thorpe for years, long after the relationship was over, spilling the sordid details to anyone who’d listen — the police, Thorpe’s wife, even his mother.

Davies (as you’d expect of the author of Queer as Folk — still enormously watchable after all these years, though they’d never dare make it now in the post-Kevin Spacey age) enters into the spirit of it all with thoroughly indecent relish. (The scene where, at his mother’s house, Thorpe sneaks into Norman’s bedroom with a tub of petroleum jelly, for example, and gets him to assume the position.) ‘Tell him not to talk. And not to write to my mother describing acts of anal sex under any circumstances whatsoever,’ he has Jeremy Thorpe say to Bessell — as probably he wouldn’t have done quite so baldly. But it’s true to the spirit of Preston’s book and, indeed, the real events; this air that the whole business is so farcical that it’s all best handled with tongue-in-cheek semi-disbelief.

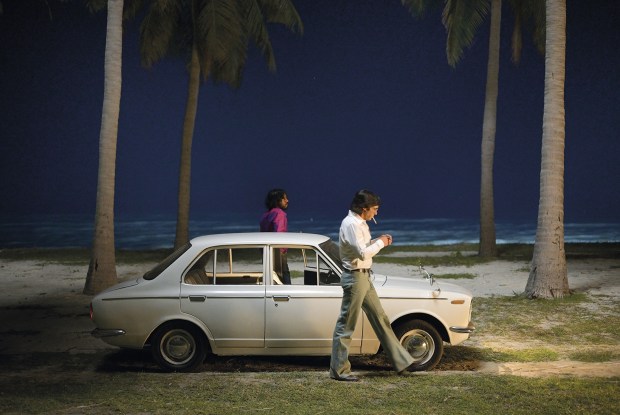

It’s so well done that I hate to raise this one objection. Are we altogether sure they had black officials in prominent security positions in Westminster in the late 1960s? I’m happy to be corrected, but it seems to me that if you’re going to go to all the trouble this production has of getting the details exactly right — the cars, the narrow bed in the grisly Dublin hotel, the badgers wandering round the Earl of Arran’s home — then it seems a jolly shame to have the whole thing undermined by the BBC’s clunky diversity casting quotas. It makes you feel uncomfortable noticing it — but notice it you do. The BBC is not being sensitive here, but belligerently rude to its viewers.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in