A conservator at Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum was recently astonished to find a tiny grasshopper stuck in the paint of Van Gogh’s ‘Olive Trees’ (1889). The discovery would not have surprised Van Gogh, who complained to his brother Theo in 1885: ‘I must have picked up a good hundred flies or more off the four canvases that you’ll be getting.’

On the evidence of a new exhibition of drawings on the theme of Artists at Work at the Courtauld Gallery, insects are the least of the plein-air painter’s problems: the 19th-century protagonist of Eduard Gehbe’s ‘The startled painter’ has been sent flying by a passing roebuck. Animals aside, there’s the physical discomfort to contend with. Jan de Bisschop’s ‘Two Artists drawing a bust’ (c.1660), hunched over their sketchbooks on a hard stone floor, have sensibly brought cushions, but Hubert Robert’s ‘Artist drawing beside a statue of Jupiter’ (1762) is perched on the sharp edge of a wheelbarrow with only a foreshortened view up Jupiter’s toga. It’s a braveartist who dares to upskirt the king of the gods, but perhaps he’s only copying the statue’s inscription.

Of all the trials besetting the plein-air painter, uninvited comments from interested members of the public are probably the worst. They were an occupational hazard for a Grand Tour vedutista like Carlo Labruzzi, whose 18th-century panorama of ‘The Colosseum seen from the Palatine Hill’, a pair of tourists with their cicerone, and an artist sketching, shows where his sympathies lie. From the determined set of the artist’s shoulders, hunkered down over his drawing board with his hat pulled down over his ears, he is doing his damnedest to block out the patronising remarks of the cicerone bending over him, without alienating the tourists who might buy the work. Unsolicited criticism from passers-by has irritated artists since the great Apelles, according to Pliny, overhearda shoemaker’s fatuous comments on his work and coined the famous phrase: ‘Let the cobbler stick to his last.’

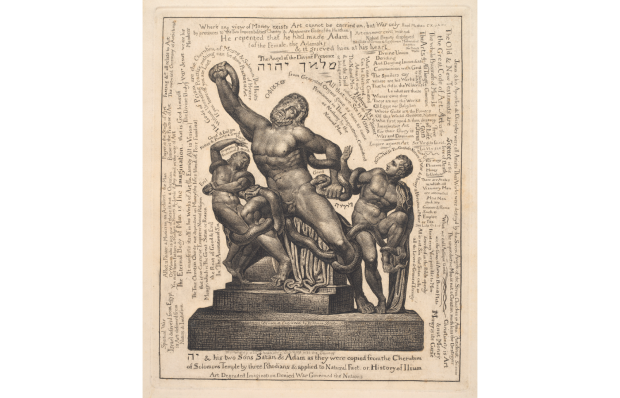

Away from distractions, the empty studio holds its own terrors when it brings the artist up against his limitations. In ‘The Inspiration of the Artist’ (1760–63), Jean-Honoré Fragonard pictures himself in despair at his drawing table with his head thrown back anda hand over his eyes as monstrous visions worthy of Goya’s ‘Sleep of Reason’ swirl around him. Fortunately help is at hand in the shape of a winged allegory of painting and attendant putti. There’s no such solace for George Grosz in a wartime self-portrait showing him at his pen-littered desk, pipe clenched between his teeth, manfully ignoring the hellish phantoms surrounding him. For the German artist watching events in Europe from exile in America, being dive-bombed by a raptor with a rat in its claws counted as inspiration. Grosz called this 1940 drawing ‘Good Times’.

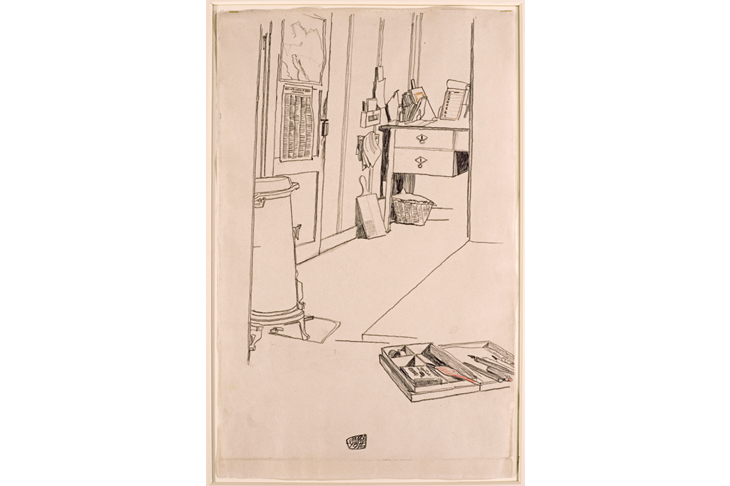

Central to the myth of the creative genius is the artist’s studio, the untidier the better. ‘The Atelier of the sculptor Remo Rossi, Locarno’ (1972) as drawn by Horst Janssen takes the prize for creative squalor — such is its state of dilapidation that only an improvised strut is stopping the skylight from falling in. The prize for neatness, surprisingly, goes to Egon Schiele for his uncharacteristically clean drawing of his ‘Office at the Mühling prisoner-of-war camp’ (1916), where the sickly artist was given the wartime job of keeping the account books thanks to his beautiful handwriting. The accounts office doubled as a studio, the pens and pencils in the foreground serving both purposes.

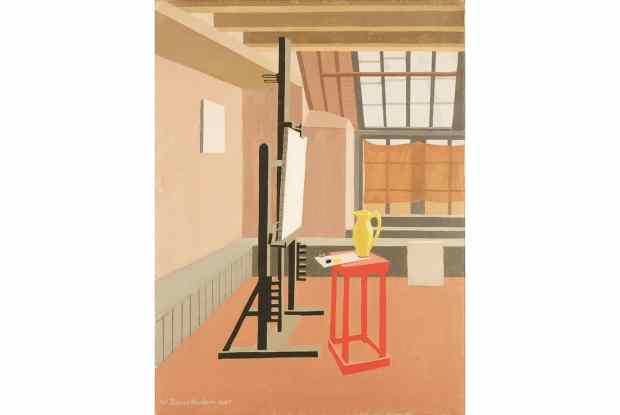

Tools of the trade loom large in studio drawings. In his ‘View of the artist’s studio’ (1882), the 22-year-old James Ensor looks over the top of a clutter of inkpots towards a portrait of his sister Marie painting a fan on the wall behind. Women artists at work appear in two other drawings. In Jules de Goncourt’s ‘Portrait of Mademoiselle Blanche Passy at an easel, wearing a man’s cravat’ (1859), the artist’s commanding posture and fierce concentration — not to mention cravat — are slightly compromised by the froth of petticoats under her overdress. Goncourt was in love with his subject and would make her the heroine of the Goncourt brothers’ 1864 novel Renée Mauperin. We don’t know the relationship between Fanny Guillaume de Bassoncourt, Baronne de Molaret, and her unnamed sitter, seen from behind in ‘Portrait of a woman artist at her easel’ (1837), but the loving attention paid to her elaborate coiffure suggests a certain intimacy.

Back views are standard in images of artists at work, especially in vistas like the anonymous ‘Landscape with an artist sketching’ (c.1606–08) where the artist fills the role of Rückenfigur, the ‘back figure’ through whose eyes we are invited to admire the view. Even here, in the middle of a mountain wilderness, the poor artist has someone leaning over his shoulder. Is there no escape?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in