One of the prettiest pieces in the V&A exhibition Fashioned from Nature is a man’s cream waistcoat, silk and linen, produced in France before the revolution, in the days when men could give women a run for their money in flamboyant dress. It’s embroidered with macaque monkeys of quite extraordinary verisimilitude, with fruit trees sprouting all the way up the buttons.

And what we know is that they were derived from the Comte de Buffon’s Histoire Naturelle, générale et particulière, of 1749–88. As Edwina Ehrman, curator of the exhibition, observes in her introductory essay, ‘choosing monkeys from Buffon’s publication… to create an embroidery pattern for a waistcoat reflected the fashionable success of Buffon’s encyclopedic masterpiece among Europe’s educated, wealthy classes… in turn, its wearer demonstrated his learning and awareness of the interest in natural history at the highest levels of society.’

The waistcoat’s lucky owner, then, was both terrifically on trend — monkeys were a fashion thing in pre-revolutionary France, in interior decor as well as clothes — and expressing a contemporary fascination with the natural order. But the waistcoat itself, being linen and silk, was also derived from nature. And it is this dual aspect of fashion, both inspired by nature and using natural material, often in problematic ways, that this exhibition is about.

The V&A is perhaps the world’s best dressing-up box, and this exhibition has exquisite pieces from its archive of more than 75,000 items of clothing. One dress makes the point vividly that the global nature of fashion was evident long before our day. It’s a dull-pink court mantua — a formal dress — of quite preposterous dimensions, being nearly as wide as it’s long with a big cane pannier underneath. But what the description makes clear is that while it was from silk woven in Lyons and made up in England, its component parts were from far-flung places — the silver lace trimmings came from the Potosi mines in Bolivia, while the stoat who provided the tail trimmings may have been Russian. As for the dyes, they came from plants and insects, some from the Middle East and North America. The agents that fixed the dye included iron; the process used copious water.

So, what seems to be merely a striking dress raises all manner of concerns that are explored throughout the exhibition: ‘the exploitation of non-renewable global resources, the promotion of built-in obsolescence and the release of pollutants into the air and water supplies’. Precisely the same issues, then, that arise in connection with the denim jeans on display elsewhere, the obvious difference being that the dress is beautiful in terms of design and execution, and, unlike our fashion, only a small number of people could afford it.

The underpinnings, the corsets made from whalebone or cane, were similarly problematic, in that the whaling industry was depleting stocks of the creatures to hold women up and in (and for other things like soap). Even so, I’d love to try a whalebone corset.

This exhibition is an interestingly two-sided affair. It has — especially the ground-floor part, from the 17th to the 19th centuries — some strikingly interesting and often beautiful clothes that derive their design inspiration from nature. There are lovely, intricate designs for cotton based on seaweed by the Irish artist William Kilburn, which would look fabulous now (Laura Ashley would have snapped them up). This is the nice bit: our fascination with nature (reflecting wider scientific interests) expressed in design.

And then there’s the problematic part: how fashion uses materials from the natural world to make clothes, and how its production depletes nature and degrades the environment. So, we go from the pretty fans of the 18th century made from mother of pearl or turtleshell or ivory — all made scarcer by the industry — to the use of albatross breast feathers inside ladies’ muffs. Part of you deplores all this but there’s another part that thinks, subversively, that they must feel fabulous.

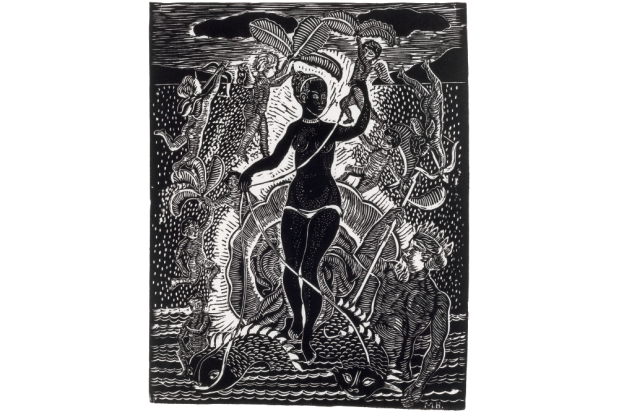

There were quite early concerns about the killing of species for fashion; the early bird conservation movement began in the 1860s. By the turn of the century, you had satirical magazines showing women as harpies — there’s a cartoon here — with claws, swooping on unfortunate birds for fashion. Some feathers seem unproblematic — if you eat pheasant why not wear ’em? — but egrets did badly out of women’s millinery, as beavers did from men’s.

So did hatters. One top hat from the collection is wrapped in plastic; it’s still toxic after a century from the mercury used in its manufacture, which turned the hatters mad. It wasn’t the only problem raw material; the connection between slavery and cotton hardly needs making.

But it’s the contemporary fashion in the upstairs exhibition that is really damaging, both in the materials used and the scale of demand. Nylons come from petroleum but other products like PVC are worse. What’s clear is that it’s not just synthetics that are damaging. Cotton grown in climates where vast amounts of water and pesticides are required are as bad. What’s needed is better labelling. If clothes have a disastrous environmental impact, what’s wrong with putting it on the label, as we do with cleaning products? The environmental audit from one dress is shown here as a till receipt; it’s a good idea.

The exhibition, however, sets out to be optimistic, with solutions as well as problems. So we meet new materials that use natural resources sensitively rather than importing them from across the world. (In this context, another exhibition, at the Nunnery Gallery in Bow on London’s indigenous garment industry, is apposite.) But really, we should do what our parents and grandparents did: reuse and alter garments, brush them down after use, and look after them, not buy new stuff endlessly. If there’s a moral from this complex exhibition, it’s that we should Make Do and Mend.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in