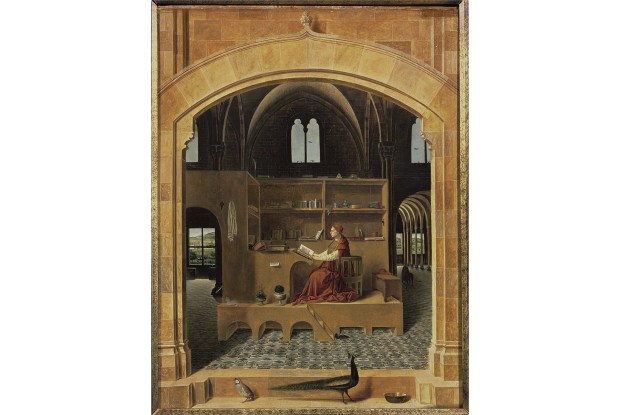

‘My Acropolis,’ Auguste Rodin called his house at Meudon. Here, the sculptor made a Parthenon above Paris. Surrounded by statues of ‘mutilated gods’, he cast himself as the Phidias of the age. His collection was part cabinet of curiosities, part charnel house. He bought Nile crocodiles and Peking ginger jars, painted sarcophagi and chipped red-figure vases.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in