‘This guy’s crazy,’ says a taxi driver, listening to a BBC interview with a man who has decided to become the first exporter of coffee from Mokha, Yemen, in 80 years. The man being interviewed, we have learned, has risked his life quite a few times over, in the most hair-raising ways imaginable it would seem, to achieve his dream of putting Yemeni coffee back on the map. We meet this taxi driver towards the end of the book, and although he does not know that the man being interviewed is actually sitting in the back of his cab, by this stage we have come to think that, yes, the man concerned, one Mokhtar Alkhanshali, is crazy.

Coffee was discovered — or, to be more accurate, the beverage invented — in Yemen. (In Ethiopia, where a goatherd first noticed how frisky his charges became after chewing the raw beans, there was little or no preparation of the bean itself.) But the region lost its pre-eminence, and by the beginning of the 21st century coffee from Yemen was of wildly unpredictable quality, and there wasn’t even much of it anyway: most coffee farmers had gone over to producing khat, which was much more profitable. And when Dave Eggers explains the economics behind the price of an ordinary cup of coffee, you begin to understand why. For a cheapish cup of high street coffee, it is important that the person who grew the crop in the first place is paid a pittance.

That said, we all know of the rise of the artisan coffee shop, whose prices and affectations surpass the ridiculous. Eggers writes in his introduction:

Before embarking on this project, I was a casual coffee drinker and a great sceptic of specialty coffee. I thought it was too expensive, and that anyone who cared so much about how coffee was brewed, or where it came from, or waited in line for certain coffees made certain ways, was pretentious and a fool.

Amen to that. But this book is not really about coffee: it is about the American Dream explicitly; and implicitly about the threat that it is under.

Mokhtar grew up in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco, the city’s most brutalised area; his first memory is of a man in rags jumping onto a Mercedes stuck in traffic and defecating on it — an extravagant, if not wholly untypical or unforeseeable example of daily life there. His family slept umpteen to a room, in two rooms. He goofed off at school but still managed to amass a small library: the Narnia books, The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter.

The itch to escape is evident from an early age. He gets sent to Yemen to stay with his grandfather in order to both shape up and learn something of his roots. Back in America, he drifts from job to job, from car-dealing to being a doorman at a staggeringly exclusive San Francisco building complex, the Infinity, where he leaps up to usher in wealthy patrons who barely notice him.

And along the line he becomes interested in coffee. Eggers’s digressions on the history of coffee are fascinating; the accounts of Mokhtar’s initial steps in setting up his own business less so. Then again, it would be hard to interest me in any account of a business being set up; others, more commercially inclined, may be less bored.

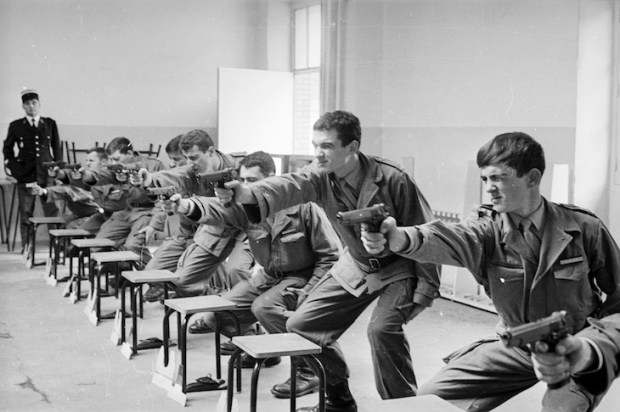

Persevere. Once Mokhtar gets to Yemen to start finding the right coffee growers, the book stops being boring, and for good. This is where it starts being a thrilling adventure story: we are in another world, of tribal warlords and civil war, roadblocks manned by 12-year-olds with Kalashnikovs, air raids, the collapse of civil society to the point where such a society becomes a distant dream, and all the while Mokhtar is trying to lug suitcases full of coffee beans back to America. Perhaps most insane of all is his crossing of the Red Sea to Djibouti in what seems like little more than a motorised punt.

Eggers has done this kind of thing before: made us look at the world from the perspective of someone from a war zone, especially in Zeitoun (2010). He does not labour the point, but we are always conscious that Mokhtar’s problems will not end at the departure gate en route to America, and that his story would have been impossible under Trump’s travel ban. Not even Mokhtar, whose resourcefulness, pluck and good fortune see him through to success, would be able to overcome such blind and hateful prejudice.

You can buy Mokhtar’s coffee for $16 a cup in San Francisco. It is, by all accounts, extremely good.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in