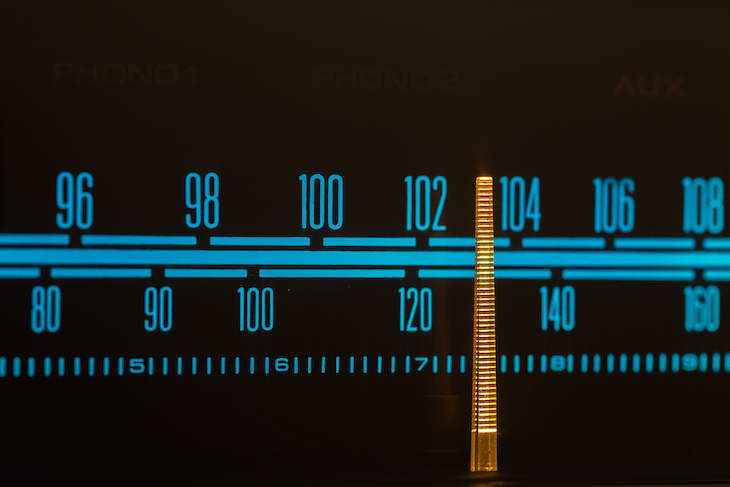

Some of us grew up worrying about reds under the bed, which was perhaps not as foolish as all that if a report on Saturday morning’s Today programme on Radio 4 is to be believed. Amid a cacophony of weird-sounding bleeps and disembodied voices, Gordon Corera, the BBC’s security correspondent (always clear, calm and collected, no matter the brief), told us about the ‘number stations’ that proliferated in the Cold War and are now being brought back to life. Anyone can tune in to them, but only those in the know can understand what they mean, and although the source of the transmissions can be traced it’s impossible to pick up those who are listening in to them, which is why they have come back into use. It’s so much safer a means of communication than email and mobile phones. No tracking possible.

These radio broadcasts are designed to be heard by spies, who have only to tune in to the designated frequency to pick up their next command simply by decoding the number sequence that’s being transmitted into the ether. Who the listeners are, where they are, cannot be established. The transmitters have been traced here, and in Virginia (a tool of the CIA), and they are very much back in use in North Korea. Their eerie, shivers-down-the-back quality emanates from that mysterious intangibility and yet their very real purpose. Also the fact that they can be heard in your living room, messages from the dark web of international espionage.

Corera took us to a house in south London where writer and researcher Lewis Bush has a battery of radios tuned in to these stations, listening live to coded messages from intelligence bureaus across the world. Bush picked up a British signal, nicknamed the Lincolnshire Poacher after its musical call sign (or alert system, indicating a message is about to be broadcast), which is based on the English folk tune. The voice was wonderfully Radio 4; the content not quite so Home Service.

After the fall of Hitler in 1945, you might have thought radio in Germany would have been tainted by its close association with the Nazis and use as a weapon of misinformation. A tool of the propaganda machine devised and fostered by Hitler and his sidekick Goebbels, the Volksempfänger, or people’s receiver, was developed; cheap radios that broadcast only German stations and which reached into the homes of half the German population. Many of these sets were still being used in the 1980s, their listeners no longer tuned in to the guttural haranguing of Hitler but enjoying some of the most experimental programming broadcast from the innovative studios of West German Radio (WDR) in Cologne, as we discovered in Radio Controlled on Radio 3 on Sunday (produced by Andrew Carter).

Funded largely by licence fee, these German stations wanted to strip their programming of Nazi contamination while understanding the power of radio to become part of the daily routine, a layer of sound that shapes a community. At first they relished the freedom of being able again to broadcast music by composers such as Mendelssohn. Far more influential, though, were the experiments in sound technology that emerged from Cologne’s sophisticated editing decks and echo chambers.

As Robert Worby argued persuasively (if a little too theoretically), radio was at the heart of the German renaissance, based ironically on the magnetic tape that had been invented in Germany as part of the war effort. Music by Stockhausen was developed in the studios and written not for performance on violins and tubas but for radio receivers at home. Within ten years, says Worby, WDR had become the world’s leading broadcaster of avant-garde music; radio as a vehicle for political change through cultural power.

Radio 4’s three-year Reading Europe project, taking us across the continent from west to east in search of the most exciting literary voices, has finally arrived in Russia. The two-part dramatisation of Alisa Ganieva’s Russian Booker-nominated novel Bride and Groom, by Bethan Roberts (directed by Helen Perry), takes us into the mountain region of Dagestan, far from Moscow, deeply divided by recent history as rival forms of Islam struggle for dominance. To wear, or not to wear, the hijab. Patya, 26, who has returned home, is warned by her family that she must find a suitable husband before she becomes an old maid. Marat, likewise back from the capital, is also under sentence of marriage, his mother fixing a date for the wedding even though there is as yet no bride. By chance they meet. Will their families countenance such a match?

On the face of it, then, a conventional tale, but Ganieva sets Patya and Marat in a world riddled with superstition and ancient folklore as well as gangs of young Muslim men protecting their territory. Marat visits a fortune-teller; Patya talks to her grandmother over the samovar. Every action, no matter how insignificant, has a meaning. The Welsh accents of the Dagestanis make it hard to believe we are in deepest Russia but the drama has a mythic quality, as if we are hearing stories told for generations, characters trapped in history yet also very much of the present.

Reading Europe was commissioned originally by Jeremy Howe, who has just been appointed as the new editor of The Archers. Phew.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in