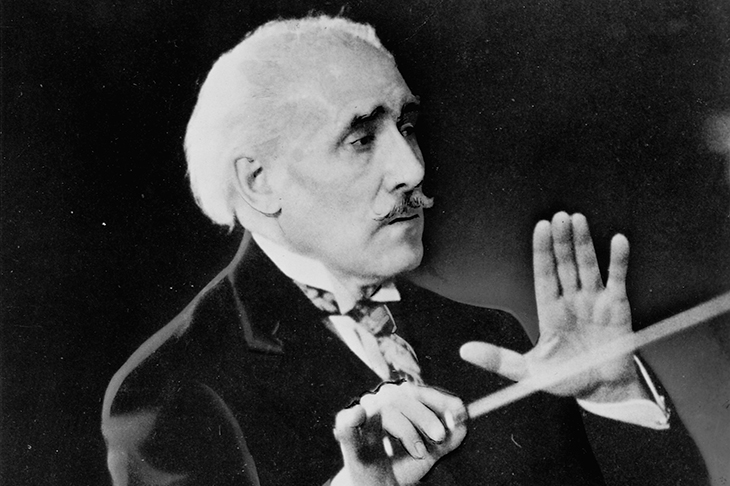

Now he is the greatest figure for me, in the world. [Toscanini is] the last proud, noble, unbending representative (with Salvemini) of the Risorgimento & 19th-century ideals of human liberty… not just a great conductor but a symbol of discipline and spontaneity in one — the most morally dignified & inspiring hero of our time — more than Einstein, (to me) more than even the superhuman Winston [Churchill].

That is Isaiah Berlin writing in 1952, two years before his hero’s last concert, and as quoted by Harvey Sachs in this magnificent biography.

Though Berlin’s encomium is extreme, it isn’t unrepresentative of the kind of things that were being written about Arturo Toscanini for many years before his death in 1957. Somehow — and it is the arduous task of the biographer to work out how — his widely recognised greatness as a conductor was bound up with his stand against fascism, his refusal to conduct in countries where fascist dictators ruled, and his nourishingly simple set of values, which made him certain of the rights and wrongs of everything to which he gave his attention. Hesitation and doubt were foreign to him, the pitiless pursuit of perfection all that mattered. To read about him at this length — and there will surely be no need for another biography — is to be simultaneously inspired and bewildered.

Sachs has written three books about Toscanini and edited a large volume of his letters, omitting most of those to his many lovers on account of their repetitive pornographic content. His much shorter 1978 biography might satisfy many readers, but the letters were discovered later, and so were many tapes which Walter, the conductor’s son, made of conversations with his father in the last years, without his know-ledge.

Sachs manages to stay just this side of idolatry, unlike many Toscanini enthusiasts, of whom the obsessional B.H. Haggin was the most extreme. More mention could have been made of the worshippers who surrounded Toscanini, since they were an indispensable element in the whole phenomenon — as, on the other hand, were those who opposed him, the most celebrated being Theodor Adorno, whose drastic critique concluded:

No work of art, no thought, has a chance of survival unless it bear within it repudiation of false riches and high-class production, of colour films and television, millionaires’ magazines and Toscanini.

Those were the days when arguments about the performances of Beethoven could prompt such wide-ranging critiques. Actually Sachs, in his book Reflections on Toscanini, has attempted his own reply to Adorno and his admirers, but it would have been good to recapitulate his argument here, since subtitling his book ‘Musician of Conscience’ already makes clear that it is something of a manifesto.

There is no question that Toscanini’s life took exemplary, quasi-mythological shape. Born into poverty in Parma in 1867, his musical gifts were so extraordinary that he was awarded a grant to go to the gruelling local musical academy, where he spent six years, only being allowed out occasionally for a visit to a local brothel, where, he said, he discovered tobacco and women on the same day, and henceforth had no interest in tobacco.

The first step in his sharp rise to fame was in Rio de Janeiro, when he was playing the cello in the touring operatic orchestra; there was a row over the conductor, and never having previously conducted, the 19-year-old got up, went to the podium, closed the score of Aida and led a successful performance from memory. He could read through a score or a play once and remember it forever. His musical ear was equally phenomenal: he could hear if a single player was doing something wrong, even in the most noisy tutti.

Those gifts, combined with a fanatical love of a wide range of music, including chamber music and solo piano music, ensured that he soon made a reputation all over Italy, and early on his career became that of the celebrity performer, and simply grew until he retired 68 years later. Furthermore, during the first third or so of his career he was a passionate advocate of contemporary music, giving the first performance in Italy of many major new works, often to the astonished gratitude of the composer. Though his last operatic performance in the theatre was in Salzburg in 1937, much of his life was spent in opera houses, above all at La Scala and the New York Met, where he and Mahler conducted during the same period.

He regarded Wagner as the greatest composer of the 19th century, but was devoted to Verdi, at whose funeral he conducted. As with many of the most significant musical performers of the time, he was unable to avoid developments in politics, and so ceased conducting in Italy, then Germany, then Austria, and throughout the second world war performed only in America, North and South.

At this point the figure of Wilhelm Furtwängler is unavoidable. His decision to remain in Germany during the Third Reich has been, and will be, endlessly debated, but for Toscanini it was unforgivable and they had no postwar contact. Furtwängler, too, claimed to be a ‘musician of conscience’; but he held to a Romantic metaphysic of music which led him to claim that there was a realm of value untouchable by the Nazis, and that politics and art were altogether separate — something which his everyday contacts sharply contradicted.

Sachs agrees with Toscanini that there could be no supping with the devil, however long one’s spoon. I can’t agree, but it is a dreadfully complicated matter. Where I think Sachs is mistaken is in seeing Toscanini’s integrity as monolithic, so that his anti-fascism is part and parcel of the purity of his music-making. Toscanini suffered from his simplicities, which means that his performances, at least as recorded — and I have listened to many, and many times — lack the flexibility and depth that we find supremely in Furtwängler’s, and in some of the other great conductors.

Furthermore, his players often sound as terrified as they must have been: it is worth going to YouTube and listening to a few of the maestro’s rehearsals, which still horrify in their sound and fury, the range of his imprecations, the breaking of his batons and hurling of his score. As Lotte Lehmann said, ‘If we weren’t good, this certainly wasn’t going to make us any better.’

And mention of Lehmann brings me to the all-too-human side of Toscanini, on which Sachs is admirably candid. One can only marvel that a man who seems to have spent most of each day in the theatre or concert hall rehearsing was able to keep so many affairs on the go. He was, in the 1930s, passionately in love with Ada Mainardi, wife of the famous cellist Enrico, and wrote her many letters vowing his exclusive adoration, and begging her to send him her used tampons to suck or wear next to his heart when conducting; but simultaneously he seduced Lehmann and vowed his kisses were only for her; while at one point he managed not only these two but a further two at the same time: he was both a serial philanderer and one in parallel. His wife Carla suffered terribly, but often, as is not unusual, once Toscanini tired of a particular mistress, Carla befriended her.

I don’t have much idea how Toscanini is regarded nowadays: to judge from what the CD stores and Amazon have available, there is still some interest, but not nearly as much as there is in some of his contemporaries and successors. No doubt that is partly due to his indifference to Bruckner and Mahler, though there is a striking performance of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony available.

In his younger days Toscanini conducted an astounding number of operas by his contemporaries and fellow countrymen, now almost all forgotten; but as with most performers, his repertoire shrank as he aged. Two performances that seem to me enduring and inspiring are his account of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Eurydice Act 2, and his 1940 Verdi Requiem, which is shattering. Elsewhere, there are many evidences of sharp musical perception, but mostly listening to his recordings makes me feel tense and anxious, either because that is the way the music itself sounds, or because I am expecting a sudden, painful jolt.

Even so, his life story is enthralling, even at Sachs’s length, and in some respects exemplary. I should add that the book itself is unimpeded by references, but they can be found online, together with the bibliography and a comprehensive chronological list of all Toscanini’s performances.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in