There are some rules of thumb in the costs of fighter aircraft. One is that the engine cost will be about 20 percent of the total aircraft cost. Another is that a twin-engine aircraft will have operating costs 20 per cent higher than that of a single-engine fighter with the same thrust. Operating costs over the life of an aircraft are usually twice its acquisition cost. For the twin-engined choice, that means paying a premium of 40 per cent of the initial capital cost as a cost of ownership.

This has literally life-or-death consequences. In recent years the US Marines have had a rise in F-18 crashes attributed to the fact monthly flight hours have fallen below the level necessary to maintain proficiency in flying the aircraft. This was due to budget constraints. If you could get 20 per cent more flying hours on the same budget, flying hours are more likely to remain above the level necessary for minimum proficiency. Being good in combat takes yet more monthly hours, which again would be aided by a lower cost of ownership. Engine reliability has increased over the last 20 years. More pilots are lost now due to bird strike than engine failure. Another benefit of a single-engine design is lower roll inertia, which helps if you want to make a snap turn to dodge a missile. All things considered, having a single-engined fighter is not a handicap relative to a twin-engined choice.

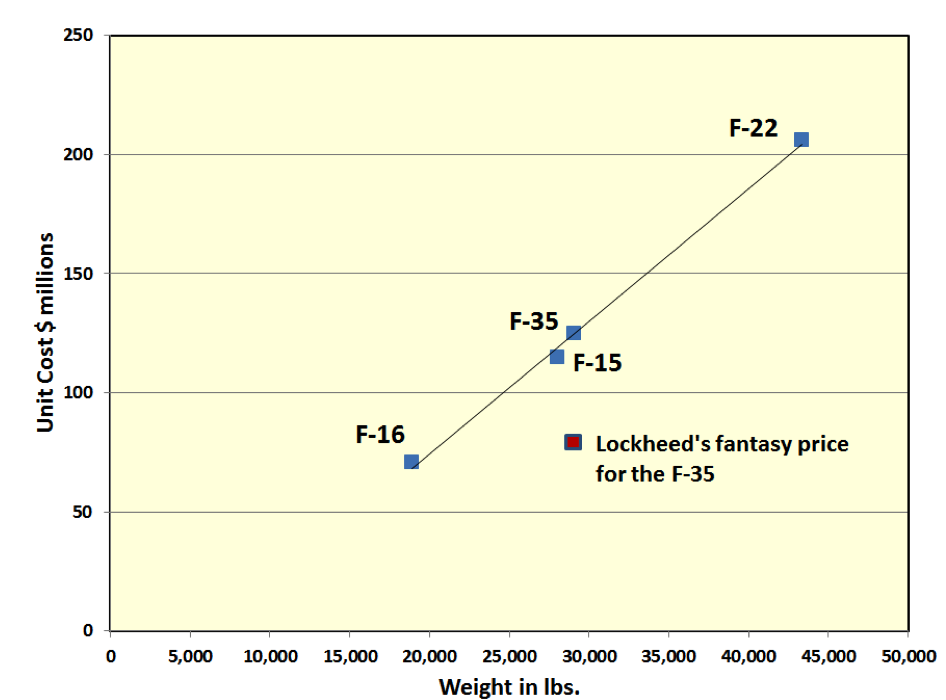

Another rule of thumb is that aircraft cost much the same on a cost per pound basis, that is that aircraft cost is proportional to weight. Which brings us to the subject of the F-35. The F-15 weighs 28,000 pounds empty and sells for US$115 million. The F-16 weighs 18,900 pounds empty and sells for US$71 million. That works out at a cost per pound of aircraft of US$4,107 and US$3,730 respectively for the F-15 and F-16. Now, at 29,098pounds, the empty weight of the F-35 is greater than that of the F-15. There is no way the F-35 is going to cost less to build than the F-15. Using the F-15’s cost per pound, the F-35 will cost not less than US$120 million, 50 percent more than what Lockheed Martin is claiming the price will fall to once they are allowed to produce the thing at full throttle.

The recent report to Congress on the costs of restarting F-22 production provides another data point – US$206 million for 43,340 pounds of aircraft. How it all plots up is shown in the graph following:

The F-35 has been in production for more than 10 years now and the price has settled down to what other fighters sell for on a dollars per pound basis. A one third cost reduction at full rate production to get to US$80 million per aircraft is simply not believable.

The next number to consider with the respect to F-35 is the claimed 20:1 kill ratio at the USAF’s Red Flag early this year. The F-35 carries only two air-to-air missiles. How the aircraft can achieve a kill-to-loss ratio ten times greater than the number of missiles it is carrying is hard to understand. Especially as the F-35 was not designed specifically for air-to-air combat, according to Lt. General Ken Wilsbach who heads Alaskan defence for the USAF. Lt. General Wilsbach also said that the F-35 needs the F-22 to protect it in combat. A few years ago General Mike Hostage said the same thing, saying that eight F-35s were needed to do what two F-22s could do. There are 125 F-22s that are combat-coded, of which 60 percent might be available at any one time to perform guard duty for F-35s. The claimed 20:1 kill ratio for the F-35 is also simply not believable.

Which brings us to a number to consider with respect to the F-35 – the proportion of the force that will be available to perform a mission at any one time. The US Department of Defense’s Director of Operational Test and Evaluation stated on page 83 of his annual report released in December 2016: “Reliability metrics related to critical failures have decreased over the past year. This decrease in reliability correlates with the simultaneously observed decline in the Fully Mission Capable (FMC) rate for all variants, which measures the percentage of aircraft not in depot status that are able to fly all defined F-35 missions. The fleet-wide FMC rate peaked in December 2014 at 62 percent and has fallen steadily since then to 21 percent in October 2016.”

It seems that the number of F-35s that can take-off for combat at any one time is one in five. It is also eleven years since the first F-35 came off the production line so there has been plenty of time for maintainers to get to understand the aircraft. If a weapon is available only 21 percent of the time then all other considerations become academic, other than the money lost and the time wasted.

It is a bad sign when a manufacturer makes outrageous claims with respect to the price and quality of his product. It is a sign that you had better start looking for something else to fill the need.

David Archibald is the author of American Gripen: The Solution to the F-35 Nightmare

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in