Never has the Conservative party been more confident about winning a general election. Theresa May’s popularity ratings have broken all records; her aim in this campaign is not just to defeat the Labour party but to destroy it. The Tory MPs who talk about ten years in power are the more cautious ones; some talk about staying in government until the 2040s.

The party’s name is seldom mentioned in this campaign. We instead hear only about ‘Theresa May’s team’, and voters seem to approve. As to what the Conservatives stand for, they’d rather not say. At times it seems they’re not even quite sure. The Tory messages revolve around Jeremy Corbyn and not much else.

Fraser Nelson and David Goodhart discuss ‘Red Theresa’ on the Spectator Podcast:

Just two years ago the Tories were denouncing ideas such as an energy price cap as ‘Marxist’. Trying to fix prices, they said, was as naive as trying to legislate for the weather. Now price caps are Conservative party policy. In 2015, Ed Miliband’s plan for an £8 minimum wage was a job-killer that would render unemployed anyone whose skills were worth less than this sum. Now Mrs May is going for £9 an hour. And her published plans involve the tax burden rising to a 35-year high.

The Ed Stone, the much-mocked slab of limestone on to which Ed Miliband inscribed his agenda, was smashed up soon after the election. He ought not to have been so bashful. Within months, several of his ideas — a national infrastructure commission, grandparents sharing parental leave, that national living wage — had been adopted by Conservatives. The idea of taxing employers to fund apprenticeships was discussed before the Labour manifesto but didn’t make it in because Miliband thought it a step too far. It is now Tory policy.

May’s embrace of the energy price cap was significant because it had been the flagship Miliband idea. And while Osborne could have been accused of raiding the old Labour manifesto, May has gone one better and seems to be actually running ahead of Jeremy Corbyn. The cap on executive pay, one of the ideas in the 2017 Labour manifesto, was a policy she ran past her own (horrified) cabinet colleagues last year. Corbyn’s plan to make it harder for foreign companies to buy British firms was also floated by Mrs May, and blocked by Philip Hammond. The disagreements between Prime Minister and Chancellor have been frequent, but they were initially kept quiet — not least because Hammond was worried about what the City would make of her interventionist instincts. But in recent weeks, the secret seems to be out and reports about Hammond’s screaming matches with May’s aides are surfacing. Strikingly, he doesn’t deny them. ‘I’m not going to say I’ve never occasionally sworn,’ he admitted this week. She, for her part, has refused to say that his job will be safe after the general election.

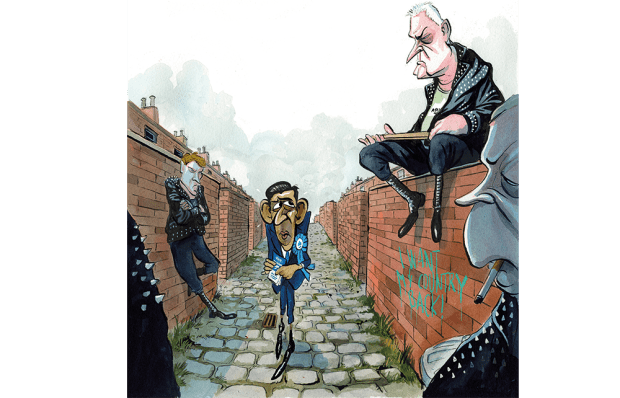

Many of Hammond’s colleagues admire his courage in defending free-market conservatism but wonder if it is politically wise – especially if the Prime Minister doesn’t really believe in it. The tension between them has become a theme of the May government: she wants to move to the left, but has been unable to do so because her Chancellor has positioned himself as a Thatcherite roadblock. He suspects Nick Timothy, Mrs May’s chief of staff, is behind this what might be crudely described as Trump-style, Britain-first economic policies.

Just as Nigel Lawson resented the influence of Alan Walters over Mrs Thatcher – and ultimately resigned in protest at being second-guessed – Mr Hammond has refused to yield to the Prime Minister’s ideas. But there is no denying that her main interest has seemed to be in committing the Tories to dirigiste policies that her colleagues had thought defeated.

So what is going on? A snap election means there is little time to discuss much — and anyway Mrs May’s cabinet has learnt not to expect to be privy to her thinking on many issues. They have three theories. The first is that her ‘Red Theresa’ act is a ruse: she’s out to win Labour party seats so she has to sound different. She’s only adopting pointless or harmless Labour pledges — many of which are merely recommendations rather than legislation, so there’s no need to worry. Mrs May was a Remainer who is now posing as the Brexit champion: election–winning Tories are nothing if not flexible. If she is bringing former Labour voters into the Tory fold, it’s natural for the party’s centre of gravity to move a little to the left.

The second theory is that she is seeking to consolidate her personal power and so she is cooking up her own agenda, which includes ideas (such as the energy price cap) that no other Tories are advocating. She is tired of being condescended to by people like Hammond, goes the theory, and hates being lectured about what conservatism is. She believes — to paraphrase Herbert Morrison — that conservatism is what a Conservative prime minister does. So this will be her election victory, not that of her party. A licence for her to do as she pleases.

There is a third theory: that she is, in her way, a moderniser, and that we are witnessing Thatcherism leaving the Tory bloodstream. The cause of smaller government and low taxes has been a hard sell since the crash, and today voters don’t seem to be buying it at all. This is not just a British phenomenon. Witness the fate of those Republican would-be presidential candidates who came armed with little more than Reagan-era clichés: they fell flat, thereby clearing the way for Donald Trump. His triumph was a disaster for the Republican Party because that party had failed to adapt.

Or look at Malcolm Turnbull in Australia, a supposed free-market liberal who has just had to capitulate and pass a banker-bashing budget. The aim was to increase his party’s standing in the polls, but it seems to have failed. So what electoral use is the free-market agenda today? It’s an uncomfortable question even for those who believe in it.

And might this agenda need modified from its Thatcher variant? You can argue that Thatcherism – a success from which the Tories never really recovered – was an effective remedy for 1970s socialism. As Milton Friedman observed, Thatcherism was also the basis for Blairism. But in recent years, the free market agenda has mutated into Davos-style globalism — which in turn has become a never-ending festival for the stinking rich. The case for what is being done by Theresa May (and, for that matter, Donald Trump) is simple: globalism has overreached itself, and needed to be dialled back. The Brexit vote was a reminder of that.

So in many important regards, Mrs May is the most left-wing leader the Tories have had in perhaps 40 years. In normal times, this would set her at odds with the MPs on the right — the ones Sir John Major once referred to as the ‘bastards’, he sort of people for whom regicide is a form of relaxation. But now, they’re happy – even loyal. This is because the Thatcherite MPs are also those who are most committed to Brexit. For years, they regarded the whole idea of leaving the EU as a dirty fantasy and even today theycannot quite believe that it is coming true. For them, the national question — leaving the European Union and crushing the Scottish Nationalists — matters more than economics, or arguments about gas bills.

As one senior Tory puts it: ‘As a Conservative I have three priorities: the nation, security, and a low-tax economy. David Cameron gave me none of those three — Theresa May gives me two. So I’ll bank those two and back her, and worry about the rest later.’ There is also a belief that Conservatism’s strength lies in being opportunistic, and ideologically flexible. So if the public want some pick-and-mix, a bit of banker-bashing with their Brexit, then Tories will cheer Mrs May as she delivers it.

The irony is that the Tories are going cold on free-market policies just at the time where their old reforms are being vindicated. What John F. Kennedy called the ‘paradoxical truth’ of taxation — that lower rates can mean higher yields — has been proven time and time again. Look at the few cuts that George Osborne did make: corporation tax rate was lowered, but corporation tax receipts are at an all-time high. When the top rate of tax was cut from 50 per cent to 45 per cent, the richest paid more than ever. Today, the highest-paid 1 per cent pay 27 per cent of all income tax collected, a statistic that should warm the heart of the most ardent class warrior. The lowest-paid 50 per cent of earners contribute less than 10 per cent to the total.

Perhaps the most spectacular success has been in cutting tax for the low-paid, a move designed to encourage more people from welfare into work. This policy, along with tax cuts for employers, has resulted in jobs being created at the fastest rate in British history. The job creation boom meant that, under David Cameron, the incomes of the poorest rose faster than anyone else’s. And this fits a trend. Wherever tax cuts are applied, the dividends are greater than expected. Yet no one seems interested in advocating them.

It’s an odd election: a Labour party that doesn’t know where it’s going wrong is pitted against a Tory party that doesn’t know what it’s getting right. When income in-equality fell to a 30-year low — an extraordinary landmark — Theresa May said nothing about it. Her focus is and must be Brexit. But must that mean ignoring such victories?

Many Tories backed Remain because although they didn’t care much for the European Union, they worried that Brexit would obsess their colleagues, and that all of the reforms — welfare, schools, taxation — would stop. So far, their fears are being confirmed.

For those Conservatives who think that the party’s role is to keep the bad guys out of power, things could not be going better. ‘If an energy price cap is the price we pay for destroying Labour in its heartlands, then I’ll pay it ten times over,’ says one MP. It’s an example of the strategic shamelessness which many Tories see as the party’s election–winning secret. When Lord Salisbury was prime minister, he said that Gladstone’s existence was the Conservative party’s greatest source of strength. Now it’s Jeremy Corbyn who is the great Tory unifier.

So the Conservatives are mutating from being the party of low taxation to the party of Brexit. They may regain their love of free enterprise when Britain has left the EU. Either way, it seems likely that in ten years’ time there will still be a clear Tory majority. And for now that seems to be all that matters.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in