I grew up with a skeleton in the attic. My mother’s clinical training bestowed on our family a short man’s dry remains, and his residency at home fed the nightmares of my siblings. When I started medical school, he came too, but now as an ally in passing the anatomy exam. On moving house, I stiffened as the taxi driver carried the loosely fastened casket in just one hand. A pavement littered with 200 bones would have been a challenging start in this family-friendly neighbourhood. My accustomed eyes were suddenly anxious to protect others from such a deathly interruption.

Carla Valentine doesn’t want her choice of job to sound pathological. ‘I held at least one human heart in my hand nearly every single day,’ she writes, knowing it seems odd that this is what she had always wanted to do. A morning’s work as a mortician might include cutting open an abdomen, syringing the fluid from an eyeball and disemboweling a foetus so that a doctor can establish the cause of death.

This is the science and art of evisceration, not the cosmetics of embalming. The process starts with an opening ‘Y’ incision (clavicle to breastbone on either side, then straight down to the pelvis). Depending on its freshness, the cadaver may be in rigor mortis or putrefying as the gut’s bacteria turn on their host. The risk of blood-borne infection requires a ‘demonic dinner lady’ uniform of steel-capped Wellingtons, waterproof scrubs, a visor, two pairs of gloves and a hair net.

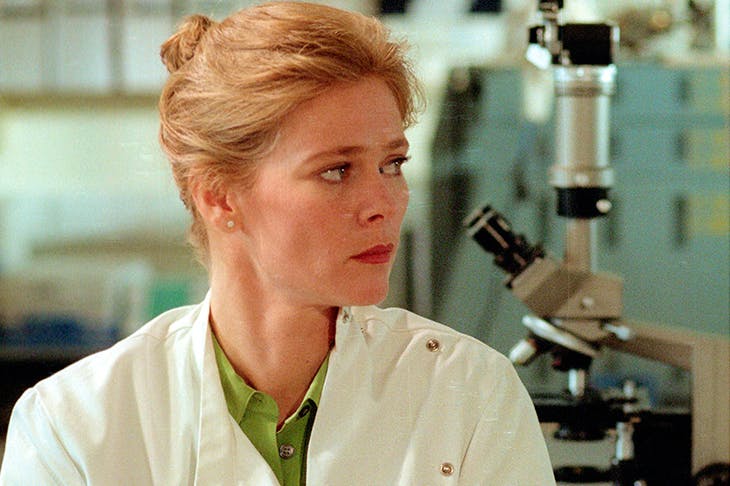

We live in a time of gore — on film, in video games and at Halloween — yet our own decomposition is almost unthinkable. Screening death from view evokes body snatching, the murderous Burke and Hare and the more recent scandals at Alder Hey. Past Mortems reminds us that looking death squarely in the eye has a venerable history, from the Egyptians to the Victorians. Valentine identifies with the ‘death-positive’ movement, which wants to tackle the mortuary’s image problem. No longer is this a vocation suited to a ‘mad-scientist’s assistant named Igor’. ‘Tiny and blonde with a huge pair of silver rib shears’, Valentine has made the female APT (anatomical pathological technician) something of a type: red lipstick, coquettish smile and an eye for taxidermy. She blogs at ‘The Chick and the Dead’, and runs a dating website for ‘death professionals’ called Dead Meet.

She probably wouldn’t expect me to like her book. Medics come off badly, like the perinatal pathologist ‘who picked up an 18-week-old foetus by his feet and dropped him on to the weighing scales, as though she was a fishmonger with a sea-bass’. ‘We have to lighten the mood in the PM room with a joke or two, no matter how serious a doctor might be,’ Valentine grumbles.

Sure, her particular interests are not for everyone (forthcoming dissertation entitled Putting the ROT into Erotic). I can’t agree that attending an autopsy is ‘like watching someone have sex’, or that the ‘scent of decomposition’ is fittingly described as ‘being kissed far too deeply by a rotting tongue’. However, there are sections of Valentine’s writing that fondly brought back my first post-mortem experience. Rather than listening to the pathologist’s monologue about coronary arteries, I was mesmerised by the painstaking focus of the APT as she rinsed a body on a nearby table, combed his hair and tweaked his stitches. No macabre bawdiness, but great professional tenderness.

Valentine succeeds in presenting her trade as a caring one. The best morticians return the deceased to a ‘respectable and dignified state’, sewing them back together with dedicated precision. In the case of a suicide under a train, the victim’s relatives are grateful when the body is reassembled. But Valentine realises she ‘did this for him, not necessarily for anyone else’. As someone who can’t help but imagine the stories behind these ends, you either start ‘caring too much and having a nervous breakdown’ or ‘caring too little and becoming callous and detached’. When Valentine endured a miscarriage herself, handling dead babies at work was understandably overwhelming.

She still moonlights in the mortuary as a locum, but the majority of Valentine’s energy is channelled into her role as technical curator at Barts Pathology Museum in London. Among the pickling jars you’ll find her readying 5,000 anatomical specimens for the public’s gaze. Children are welcome. By bringing the skeletons out of the attic, Valentine has revived a once-neglected collection and enabled it to meet the present.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in