Ceci n’est pas une Partenope. Forget the warring classical kingdoms of Naples and Cumae: this is surrealist Paris in the 1930s and imminent invasion is the stuff of conversational parenthesis, barely worth interrupting a rubber of bridge for, let alone an embrace. Man Ray, Lee Miller and their androgynous associates slink and affect their way around a monochrome salon with its suggestively curved central staircase, offering up the performance of themselves as a living exhortation to make art, not war.

As a response to Handel’s most Shakespearean of comedies, Christopher Alden’s production is inspired — more now, if anything, than in 2008 when it was new. There’s a new kinship, a self-reflexive friction to watching these languid baroque Charlestons as our own world dances closer and closer to the brink.

Denial has rarely looked so good or pulsed with such a genuinely erotic charge. The gender-bending of Handel’s original prompted one contemporary to dismiss its heroine as a role ‘only fit for… some He-She-thing or other’. It’s a discomfort Alden seizes on, celebrating and amplifying it in the sensual play of his characters, their desires as deliciously ambiguous as the nude cubist collage that Emilio (an excellent Rupert Charlesworth) creates — a faceless play of flesh, interrupted only by a single nipple. Point made.

But if Andrew Lieberman’s gorgeous designs have a strong Parisian accent, and Christian Curnyn’s pit is all thrusting Italianate swagger, Amanda Holden’s translation is earthily Anglo-Saxon, fuck-and buggering its irreverent and witty way through a plot with added toilet humour (a nod, surely, to Man Ray’s friend and collaborator Duchamp) and some giddy cross-dressing. It’s exhilarating stuff, and a reminder of how rarely ENO really takes dramatic advantage of its opera-in-English policy.

When a plot is as frothy as Partenope’s you need some pretty sparkling performances to keep things buoyant. Step forward Sarah Tynan’s sex kitten of a queen, her tone as bright as the chink of ice cubes in a cocktail shaker and every bit as brittle, softening into something more fragile for ‘Qual farfaletta’, turning mellifluous by the time Act III’s closing ‘Si, scherza, si’ arrives.

She’s courted by a trio of would-be lovers led by Patricia Bardon’s charismatic Arsace, stopping time and stilling comedy for a magical moment in ‘Ch’io parta’ — a sleight of hand more potent even than the rabbit Armindo (James Laing) quite literally pulls out of a hat. Gamely comic, both Laing and Matthew Durkan’s Ormonte give everything in pursuit of a gag, and if the production doesn’t find quite the same play of emotional light and shade as the black-and-white photographs that inspired it, it’s a loss you hardly miss among so much wit and surreal invention.

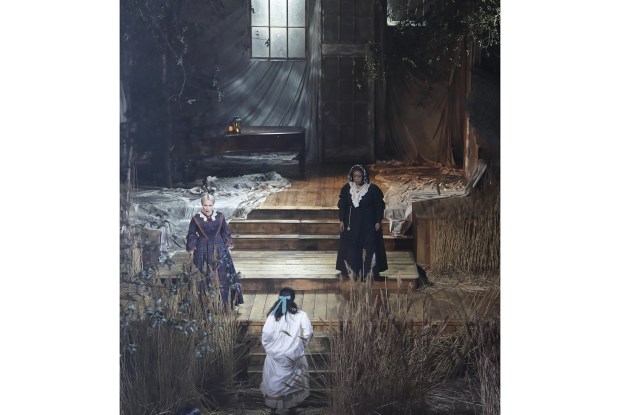

War invades the bedroom in Partenope, but Handel’s Faramondo sees love set up camp on the battlefield. For a plot that finds three nations in conflict it’s remarkably short on actual action — Chekhov’s gun (or, here, his flick-knife) hangs unused for nearly three hours. The music, too, while pretty, lacks arias capable of inflicting much more than a flesh wound. In William Relton’s 1960s update for the London Handel Festival, armies become gangs, fighting a turf war in Gustavo’s — a not-nearly-seedy-enough nightclub. Like Alden, Relton wisely pays little attention to the story, which, in this case, hinges on a baby-swapping subplot that remains conveniently unexplained. But, unlike Alden, his reworking feels awkwardly superimposed, never fully integrated into action that’s baffling enough without the coyly historical English surtitles that would scarcely have frightened the ladies at the 1738 première.

Lawrence Cummings conducts a mercifully brisk performance, supporting a Royal College of Music cast led by thrilling Swedish mezzo Ida Ranzlov and soprano Harriet Eyley, whose dipsomaniac Clotilde provides most of the evening’s very few laughs — knocking out clean coloratura while knocking back the vodka.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in