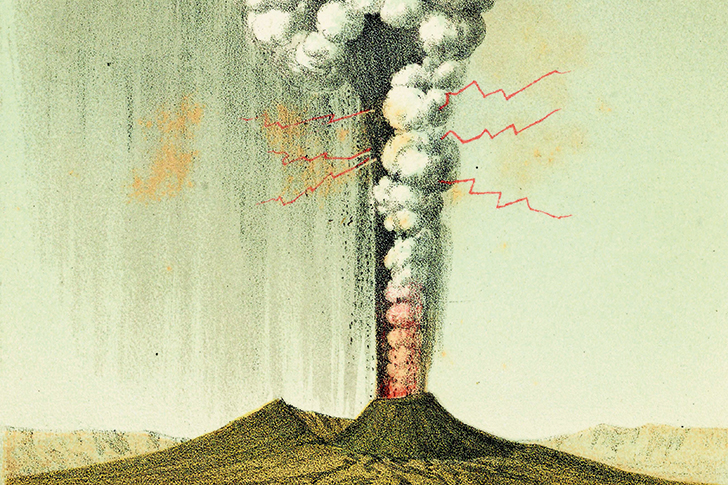

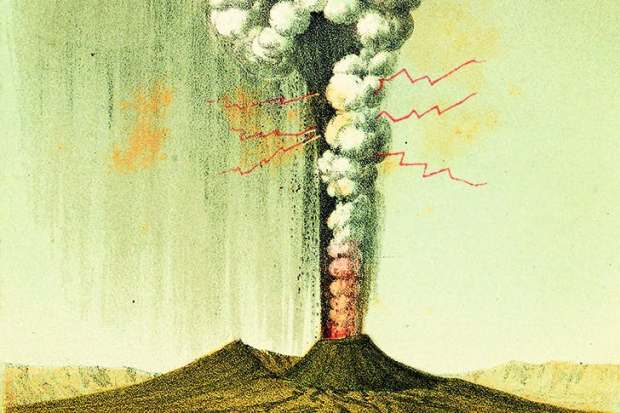

In the mid-6th century, legend has it, St Brendan set off from Ireland with a currach-load of monks on a mission to find the Isle of the Blessed. The Irish like to think that his Atlantic odyssey took him to Newfoundland before the Vikings; what seems more probable, if you believe the medieval account, is that it brought him close to the shores of Iceland where he passed a mountainous island with ‘a great smoke issuing from its summit’ and ‘flames shooting up into the sky’.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in