Here in Munich, in the gallery that Hitler built, this year’s big hit show is a spectacular display of modern art. Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965 is a massive survey of international modernism, curated with typical Germanic can-do. Talk about ruthless efficiency — even the catalogue weighs several kilograms. All the stars of German modern art are here, from Joseph Beuys to Gerhard Richter, but the most interesting exhibit isn’t in this huge central hall, where Hitler staged his Great German Art shows, it’s in a quiet corner of the gallery, at the end of a deserted corridor, up an empty flight of stairs. Haus der Kunst — The Postwar Institution, 1945–1965 charts the transformation of this bombastic building from a shrine of Aryan art to a temple of the avant-garde. It’s a fascinating insight into the history of the Haus der Kunst, a museum that became a battleground in the Kulturkampf between traditionalism and modernism — a battle the modernists won, eventually, but at a terribly heavy price.

Hitler erected the Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) to showcase the fine art of the Third Reich. The museum’s opening show, 80 years ago, was the Great German Art exhibition of 1937. The Führer supervised the selection. The focus was on healthy Teutonic heroes (soldiers, farmers, virgins, mothers), depicted in an archaic, academic style. Anything negative or experimental was condemned as Jewish and/or Bolshevik. Only art that glorified the Fatherland was allowed.

The conventional wisdom is that everything Hitler approved was rubbish, and everything he vetoed was superb. It’s convenient and comforting to believe that tyrants have no taste, but the truth is a bit more complicated — and a lot more interesting — than that. Hitler persecuted some of the greatest artists of the 20th century. He promoted a vast amount of tat. However, between the Alpine kitsch he loved and the modernist masterpieces he hated lay a lot of artworks whose merits were less clear-cut.

Only a few of the artworks in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst were overtly fascistic. It was seeing them all together that made them so. The majority were merely old-fashioned: muscular nudes, aping the warriors and athletes of antiquity; standard genre paintings, with an emphasis on rural toil. The propaganda value was often confined to the titles: a landscape became ‘A German Landscape’; a family became ‘A German Family’. Most of these tidy daubs would have graced a bourgeois drawing room — there was nothing revolutionary about them. That’s what made them so seductive. The most telling thing about this show was the art that wasn’t there.

The Nazis were ruthless in removing modernist art from German galleries, and in 1937, right across the road from the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, they mounted a parallel exhibition of the art they most despised. The list of artists in this Degenerate Art show reads like a Who’s Who of German modernism: Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee… Unwittingly, Hitler had assembled the greatest modernist exhibition of all time.

The close proximity of these two shows was no coincidence. The idea was to visit both of them, and make a direct comparison between the two. It was clear what conclusion you were supposed to draw. The Great German Art show was presented in a reverential atmosphere, in the palatial Haus der Deutschen Kunst. The Degenerate Art show was crammed into Munich’s far smaller, fustier Archaeological Institute — like bric-à-brac in an old junk shop. Mocking slogans told the viewer exactly what to think.

Both exhibitions were popular, but there was no doubt which was the bigger draw. The Great German Art show attracted half a million visitors. The Degenerate Art show attracted two million. It’s impossible to calculate how many came to bury these modernist artworks and how many came to praise them, but the disparity between these attendance figures suggests that ‘degenerate’ art had lots of fans. The Nazis thought so too. The Great German Art show became an annual event, but the Degenerate Art show was not repeated. The Nazis burnt a thousand modernist paintings. The rest were flogged off to foreign buyers at an auction in Lucerne.

The contents of these two shows are usually presented as chalk and cheese — rabid reactionaries in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, daring progressives in the Archaeological Institute. Actually, both selections were riddled with ideological contradictions: ‘degenerate’ artist Emil Nolde was a member of the Nazi party; Goering commissioned portraits by ‘degenerate’ Georg Grosz (and helped himself to confiscated artworks by ‘degenerates’ like Munch, Gauguin and Van Gogh). Franz Marc’s ‘Tower of Blue Horses’ was removed from the Degenerate Art show after protests by war veterans (Marc had died fighting for the Fatherland in the first world war). Nazi artist Adolf Ziegler (nicknamed ‘the master of German pubic hair’ on account of his pervy Nordic nudes) curated both exhibitions, and inadvertently included works by German sculptor Ernst Barlach in each of the displays.

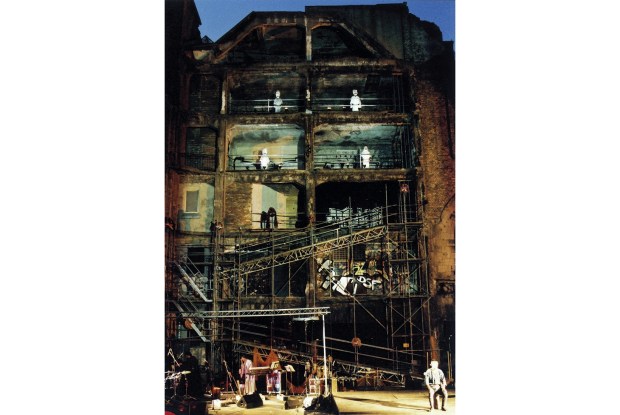

In 1945, after 80 air raids, most of Munich lay in ruins. The Haus der Deutschen Kunst and the Archaeological Institute were among the few public buildings to escape unscathed. After a short spell as an American officers’ club, the Haus der Deutschen Kunst became a gallery again, dedicated to promoting modern, international art. Renamed the Haus der Kunst, it put on an exhibition of Der Blaue Reiter (Munich’s expressionist pioneers, led by the ‘degenerate’ Franz Marc) and a retrospective of Oskar Kokoschka, a veteran of the Degenerate Art show. The museum marked its silver jubilee with a rerun of the Degenerate Art show (but without the angry Nazi slogans). For post-war Germans, modernism now reigned supreme.

The old Archaeology Institute, which staged the Degenerate Art show, now houses the historic Munich Kunstverein. Before the Nazis came along, this artists’ guild was a bastion of conservatism. Now, even this august institution has embraced the avant-garde. Thanks to the Nazis, and their crass aesthetics, traditionalism ended up on the wrong side of history. In Germany modernism remains the new orthodoxy, as it has been since 1945.

Yet at the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich’s answer to Tate Modern, there’s a sign that things are changing. Amid the usual trawl through 20th-century modernism, one room has been set aside. ‘Artists under the National Socialists’ comprises only 11 paintings but it’s the most interesting room in the whole museum. It shows that in Nazi Germany, things were rarely black and white. For every diehard Nazi or ‘degenerate’, there were dozens of artists whose political position was more vague. Some supported the regime then turned against it. Others opposed it, then gradually acquiesced.

Dominating this display, on show here for the first time, is ‘The Four Elements’ by Adolf Ziegler. Of course when you know how Ziegler sucked up to the Nazis, and hounded brilliant artists like Beckmann and Kirchner (Beckmann driven into exile; Kirchner driven to suicide), this painting seems revolting. But when you strip away that knowledge, something far more challenging emerges. It would be so much easier if bad men and bad politics made bad art. If only life were that simple. But when you look at this picture with fresh eyes, you’re forced to acknowledge an awkward truth. Despite the repugnant morals of the man who made it, it’s actually not that bad.

Ziegler’s work is too close to the Third Reich, too complicit in its crimes against humanity, but several other paintings in this room are strong enough to stand alone, regardless of the time when they were made. Eighty years ago, modernism was bold and radical, realism was reactionary. Today, the most risqué show in Germany would be a display of realistic art.

House of Art — The Post-War Institution, 1945–1965, is at the Haus der Kunst (www.hausderkunst.de) in Munich until 26 March.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in