As the dreaded season of goodwill approaches, the Royal Opera has mounted two revivals of pieces that are interestingly contrasted: Puccini, in the first characteristic and successful opera of his career, though with a lot still to learn, and Offenbach, with the incomplete last work of his career, but a radical departure from all the successes he had had before, and a work that is ultimately a noble flop.

Les Contes d’Hoffmann is one of the Royal Opera’s most venerable productions, dating from 1980 and having its eighth revival, with William Dudley’s elaborate sets. One might even call them cluttered, and their major disadvantage is that they necessitate not only two lengthy intervals but also several long and dramatically tiresome pauses just when you hope that the evening is going to develop a little momentum. Hoffmann is one of those pieces that has too much good music in it to let it sink, but also longueurs of stunning dullness. I look back to those happy days of highlights on LPs. As it is, the evening was only a few minutes under four hours, and you need to have an interesting central figure to rivet the attention for that long.

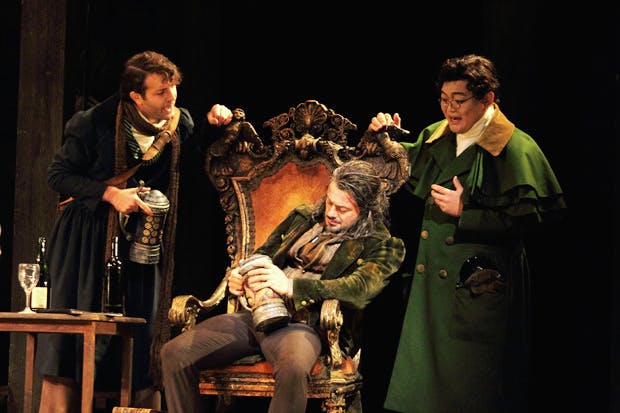

Hoffmann is a miserable creature, a commonplace creation who simply has bad taste in women — a mechanical doll, a Venetian whore, a terminally ill maiden. We were fortunate in that Vittorio Grigolo brought as much colour and vigour to the role as possible, his wonderful freely projected voice growing in size and intensity as the evening progressed. He has become one of the most appealing tenors of our time, and he is reliable too. He had a choice set of non-lovers, but his muse/companion Nicklausse, sung by Kate Lindsey, outshone them all and was the female star of the evening, though Christine Rice, as Giulietta, the Venetian, was marvellous in her far too small role. Dudley’s Venetian set may well outdo anything Las Vegas can offer in that line, and the music of that act, with the mysteriously profound Barcarolle (reprised by the orchestra during another change of scene), is the finest in the score. The other women in Hoffmann’s life were fine, though Sonya Yoncheva was wasted in the role of Antonia. Thomas Hampson, who talks so interestingly about music, is imperturbably bland as always as the four villains. Evelino Pido didn’t seem to have his heart in the score, conducting especially the tedious Prologue far too sluggishly. Offenbach understandably didn’t seem to realise that the sadness he was so eager to express was already there at the heart of his finest operettas, just as it is in the finest of Johann Strauss’s — who did realise it.

Manon Lescaut

Manon Lescaut was the first revival of Jonathan Kent’s production of 2014, with sets by Paul Brown. I didn’t see it first time round, and won’t mind not seeing it again. Updated to the latter part of the last century, the Abbé Prévost’s unengaging story (why/how has that novel stood the test of time?) makes no sense, with Manon hanging around under the inevitable street lamp and explaining that she is being sent to a convent. In Act Three, where Puccini hits top form, the roll-call of sex workers, as they emerge from prison and are shoved on to a boat to America, is also absurd, the more so in that it allows a contributor to the programme to write an article about the sex trade that clearly implies that Puccini’s melodrama makes some kind of contribution to what is a terrible and serious problem. Puccini is simply not a composer on that level, except in Madama Butterfly. The Act Three scene provides him with an opportunity for horrified chanting, for Manon’s thrilling despair and Des Grieux’s hysterics, adding up to enjoyable thrills for the audience. After that Manon Lescaut becomes merely maudlin: death scenes should be pretty brief, otherwise they are nauseating and deserve a Wildean put-down.

Brown’s set in Act One is a housing estate, with heterogeneous classes of inhabitants, and one of the first examples of what has become an opera-set cliché, a winding staircase. In that setting the comings and goings and their rationale are ludicrous, and so, even more, is Act Two’s’s rococo bedroom in which we see the bored Manon of Sondra Rodvanovsky. She is magnificent, a tart who discovers too late that she has a heart, and a sumptuous smoky voice to match, one of the sexiest since Leontyne Price. Aleksandrs Antonenko is the vocally over-endowed Des Grieux. In his delightful Act One aria — Puccini striking gold for the first time — Des Grieux may be right in singing that he has never seen a woman like Manon, but she could have replied that she had never heard a man like him. In the desperations of Act Three he came splendidly into his own. Neither was at their best in Act Two, a terrible mess dramaturgically, which Puccini wouldn’t have tolerated later. Maybe the star of the evening was Antonio Pappano, conducting with passionate conviction, not attempting to give a shape where there is none, loving every note.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in