The catalogue to Pallant House Gallery’s latest exhibition features a favourite anecdote. It is 1924 and a competition is being held to find the woman with the most pleasing vital statistics. As a paradigm, the judges choose the Venus de Milo. Thousands of women queue up to find out whether their measurements — not only bust, waist and hips, but thighs, calves, neck, wrists even —approximate closely enough to those of the ancient sculpture to earn them the prize of £5. No one thinks to mention that the Venus is missing both arms.

Classical myth was all the rage after the first world war. When the world felt like chaos, it was only logical to go back to the beginning. The Greek poets, after all, pictured Chaos not as the end of time but as the original divinity, before whom there was nothing. Chaos offered the opportunity for a fresh start.

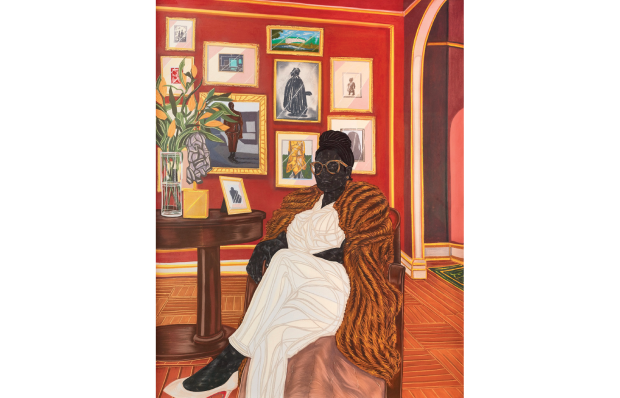

The curator of this wide-ranging exhibition proposes that British artists sought a ‘return to order’ in the interwar period by rekindling ancient motifs. Just as James Joyce and W.B. Yeats used classical references as ‘a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history’, as T.S. Eliot put it, so Henry Moore, Vanessa Bell, Edith Rimmington and others are envisaged as employing a ‘Mythic Method’ to make sense of the world.

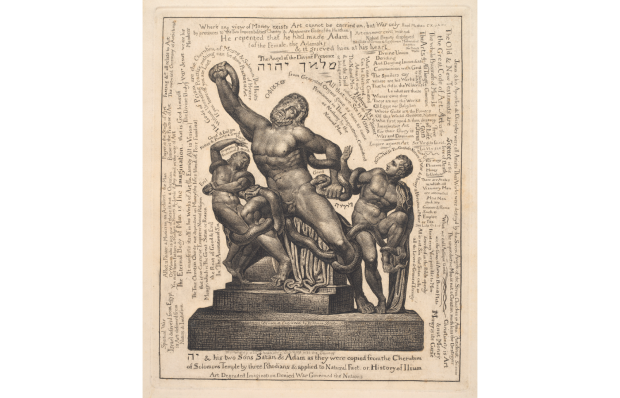

Their work is certainly full of Greek and Roman imagery. Lyres and labyrinths, columns and inscriptions, urns and kraters in neat, orderly lines, drained of wine. Voluptuous, semi-nude women recline on lawns and chaises-longues so velvety you cannot see the brushstrokes. An Ionic temple crowded with classical allegories and Christian saints lends dignity to a scene of British soldiers preparing for battle and their families for loss in Frederick Cayley Robinson’s ‘War Memorial to the Students of Heanor School in Derby’ (c.1919–23).

After decades of the avant-garde, you can see why many artists found the classics so defining. It wasn’t just the precision and familiarity of the architecture that appealed, but the themes of the poets, particularly the tragedians, who knew that loss was a necessary part of life, and determined to make the best of both. As James Joyce paired Leopold Bloom with Ulysses, so the warriors of the Iliad compared themselves to the bigger, mightier men of yesteryear whose greatness — and existence— was open to doubt. And so British artists of the 1920s and 1930s looked to Greek myth for legitimacy, only to lose themselves in false dreams.

Artist Harry Morley, one of the many less familiar names in this show, was so spellbound by ancient visions of Arcadia that his ‘Apollo and Marsyas’ (1924) has become a jolly concert champêtre rather than the usual bloody scene of flaying. Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, meanwhile, clearly had great fun reimagining the ancient Muses for John Maynard Keynes’s college rooms at Cambridge. Their bright murals (the cartoons for which are on display) featured languidly draped women and loincloth-sporting men leaning against columns, clasping musical instruments, and reading from scrolls. If art, craft and flesh offered relief from the death-dealing machines of war, as their murals proclaimed, it remained to be seen whether learning really was divine.

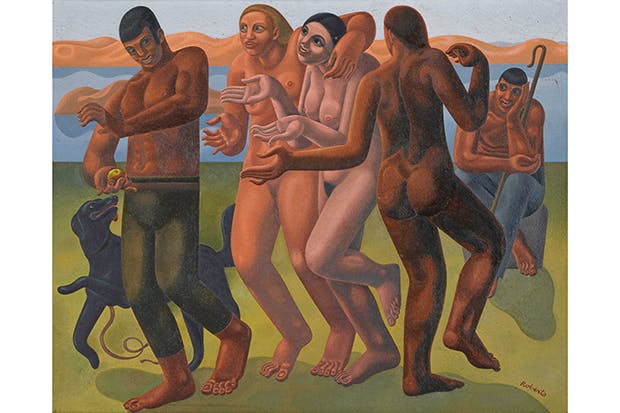

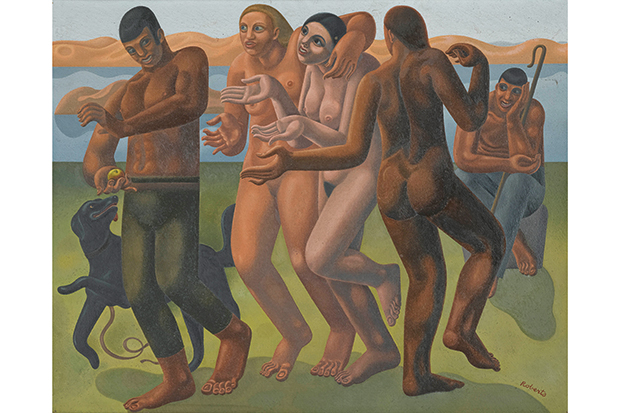

It’s interesting to recall that when Chaos generated life in Hesiod’s Theogony, it spawned Darkness and Night. The dark humour of the myths was probably in fact the artist’s most useful tool for illustrating human absurdity and the capriciousness of fate. Look, then, to the three goddesses in Royal Academician William Roberts’s ‘Judgement of Paris’ (1933), who carouse like drunken oiks. The dejected typist of Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ finds her counterpart in Roberts’s compliant-looking Paris. Even the most ridiculous scenes have a dark undercurrent, because while the classical was authoritative, it was also imperfect.

The ‘panorama of futility’ is only too evident in the exhibition’s landscape paintings. John Armstrong, who designed the costumes for Robert Graves’s I Claudius, served in the Royal Field Artillery in Egypt and Macedonia during the first world war before painting ‘The Labyrinth’ and ‘ Psyche on the Styx’ (both 1927). Like many of his contemporaries, he favoured tempera over oil paint, since it gave sparse scenes like these the requisite impenetrability and aloofness. In ‘The Labyrinth’, nude Ariadne lurks by the entrance to the maze, while nude Theseus races through it. If he reaches the middle, he will encounter a lazy sloth of a Minotaur. And then what?

By the time Armstrong turned to classicism again on the eve of the second world war, futility was metamorphosing into nightmare. The Third Reich was appropriating classical ideals for its own ends. Armstrong’s ‘Pro Patria’ (1938) offered a disturbingly prescient scene of ruined masonry and dead vegetation. Tourists had long been used to clambering over ancient ruins and making garden follies of them. They could no longer look at the fractured ancient monuments in the same way when the buildings they once inhabited came to resemble them so closely in the wake of the Blitz. By then, the modern world no longer needed to be given meaning and shape through a mythic method — it merely needed to survive.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in