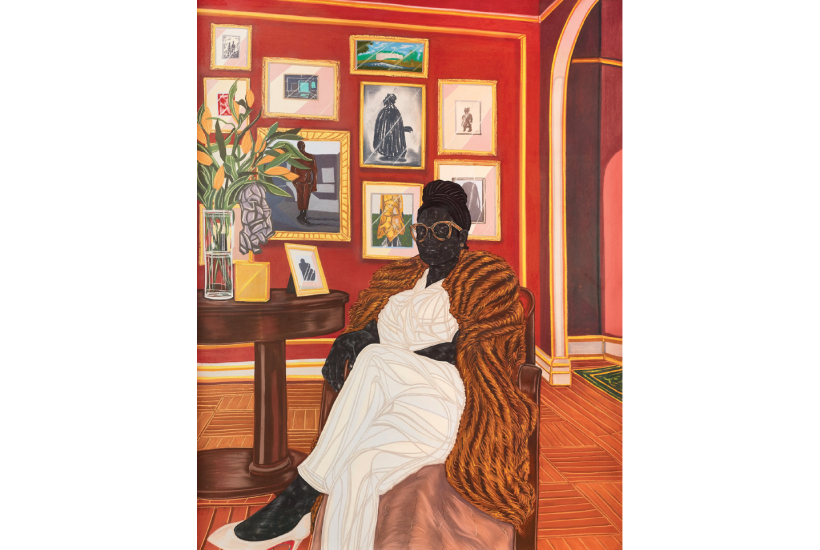

A wave of totalising race-first exhibitions has swept through UK art institutions of late. The National Portrait Gallery’s remit of ‘reflecting’ British society could reasonably make one wary of its turn at the same project. Indeed, a false, stilted language accompanies curator Ekow Eshun’s The Time is Always Now. To have some 20 artists ‘reframing the black figure’ somehow sounds both ambiguous and politically predetermined.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in