A white van pulls up outside St Giles in the Fields, an imposing 18th century church in central London, around the corner from Tottenham Court Road station, for a couple of hours every Saturday afternoon. St Giles is known as ‘The Poets’ Church’ because it has memorials to Andrew Marvell and George Chapman, but this humble van makes the nickname more fitting. It’s a library.

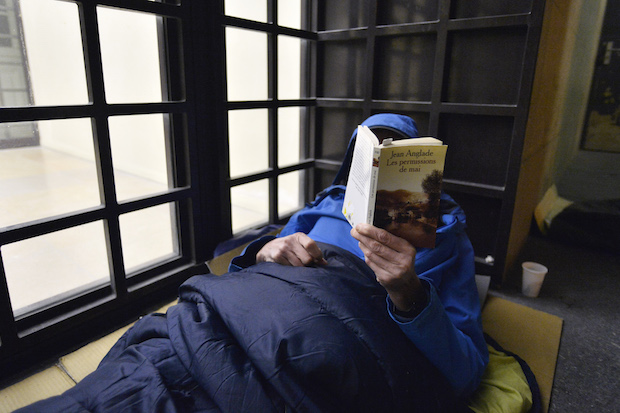

To be homeless is to have no fixed address, which means you can’t borrow books from a public library — but it doesn’t mean you’ve no desire to read. Quaker Homeless Action set up this mobile library in 1999, making runs into London twice a week and lending books to more than a thousand homeless people a year. Borrowers only have to give a first name, which isn’t always their real name, and may take out two books for up to two weeks, although only around a third are actually returned.

The van hasn’t long been parked when a young man called Noah takes out Split Second, a crime novel by David Baldacci. I ask him why he chose it. He stares at me, startled. ‘I’m sorry,’ he says, in speech so halting there are almost as many pauses as words. ‘I’ve never been asked that before… I have a lot of prepared responses… People generally say the same things… Nowadays I try not to think about why I do things… You rather live down here than up here.’ He points first to his boots, then to his head.

There are around 40 people gathered in the churchyard — mostly men, in their thirties or early forties, which aligns with what we know about homelessness in London. According to Chain (the Combined Homelessness and Information Network database), six in every seven of the just over 8,000 people who slept rough at some point in London last year were male, and more than half were aged between 26 and 45. There is a wariness in the air: many of the men stand alone and conversation is stilted.

‘They might not have spoken to anyone for a while,’ says John, one of the volunteers, who explains that the library exists as much to provide access to a friendly face and someone to talk to as to distribute books. ‘Even in hostels,’ he says, ‘you often can’t trust the people you’re living with, and get robbed.’ John has been volunteering for the mobile library for eight and a half years, and before that was homeless and a user of the library himself. The charity Crisis reports that homeless people are significantly more likely to have experienced violence or been robbed than the rest of the population; the lack of conversation begins to make sense.

Ross, whose abundant curly hair is rather greyer than Noah’s, is greeted as a regular and sits down beside us, saying little. I notice that one of his carrier bags is from the Book Warehouse, and he thaws slightly when I tell him that I also work in a bookshop. ‘I rarely borrow a book,’ he says, dismissing the library’s collection for not having a big enough history section. Another disappointed borrower, also called John, took a dim view of Frederick Forsyth’s The Fourth Protocol. I ask him about his favourite writers, and he becomes increasingly animated as he talks about sci fi, specifically Alastair Reynolds, Olaf Stapledon and George Orwell. In a matter of minutes his reserve has disappeared, so I ask a little about his day to day life. ‘I don’t have an Oyster card or anything,’ he says. ‘Wherever I go I walk, so it’s more or less the same area, but occasionally I spend a few days in Richmond — it takes me all day to get there, and a whole day to get back, so I spend a few days there.’

I ask him where he stays: ‘You never tell anybody where you sleep.’ But he smiles as he tells me the codenames for churches which provide meals, used so as to stop ‘the wrong kind of people’ turning up. ‘One church we call Stringfellows,’ John explains. ‘Another one we call Spearmint Rhino, there’s another called Secrets, and we’ve got one called Annabel’s.’ We are both laughing. Has he got friends, then, in Richmond? His answer comes quietly: ‘You do your own thing, really. You meet people, you know people, you know who not to know.’

A homeless lady called Patricia arrives breathless with enthusiasm about Hilary Mantel’s A Change of Climate, which she was given, has read and now wants to pass on. ‘I love Mantel,’ she gushes, so we discuss Wolf Hall and — her favourite — A Place of Greater Safety. She loves John Banville and Milan Kundera, urging: ‘You absolutely must read Night Train to Lisbon by Pascal Mercier.’ Her appearance is almost as sophisticated as her taste in literature: she looks to be in her sixties, and wears a chic top and delicate gold earrings. She tells me a complicated story about her Australian bank account being closed down due to inactivity. Perplexed as to why she uses the library, I ask the volunteers about her, to be told, sadly: ‘She’s a fantasist — every week she has a different story.’

As the library is packed away, another user, Carol, in her forties, shyly sidles up to the volunteers. ‘Please don’t buy these,’ she begins, ‘but if you happen to come across them will you let me know?’ She writes down on a slip of paper Land Without Thunder and The Promised Land, both by the Kenyan author Grace Ogot. Carol explains, ‘What people from my book club have been telling me is that they don’t read novels any more, they only read the newspaper — but they would like to read, so we’re showcasing short stories.’

At first, the book club at her hostel ‘was ghastly and very poorly attended. You need to know your audience,’ she says. As several Eritrean women are staying there, Carol decided to start a new book club, focusing on literature by African women. There weren’t funds to provide everyone with a copy of the book, so she set it up online. Members pay a fee of £12 a year — enough for Carol to upload one copy of each book to the website, thereby making it available to everyone. She says the discussion takes place on an online forum, rather than in person, which makes me wonder if homeless people — like so many of us — find it easier to belong to communities on the internet, rather than talking to one another face to face.

By the time the library closes, 14 books have been borrowed and six returned. Many of these transactions might have seemed perfunctory, but each occasioned at least an exchange of a name (albeit sometimes invented), a line or two of conversation, and a smile. According to Crisis, more than a third of homeless people in the UK say they often feel isolated and lack companionship. This was all too palpable that Saturday afternoon, but books are a way to counter this. The mobile library is a much needed hub around which conversations stutter into gear.

The post Words on the street appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in