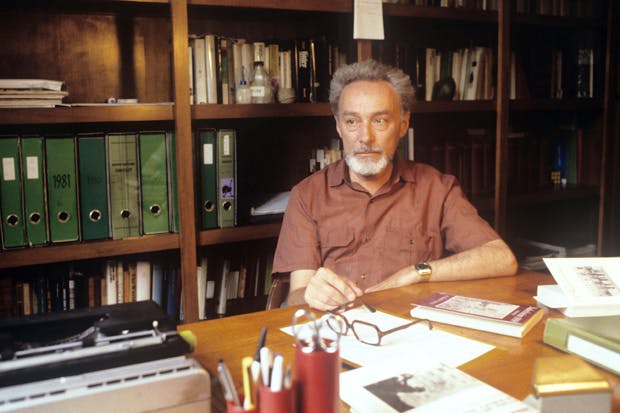

It was hard to believe that Monday morning’s introduction to the Italian writer Primo Levi on Radio 4 lasted for only 15 minutes. It was so rich, multi-layered, filled with meaning. Presented by Janet Suzman, it was intended as a fanfare for the 11-part adaptation of Levi’s most original book, The Periodic Table, in which he explores the chemical elements by equating them to episodes in his own story. Levi, an Italian chemist, was captured by the Nazis as a resistance fighter and a Jew, and at first detained and later sent to Auschwitz. His science training and his knowledge of German saved him from the gas chambers; and a timely bout of scarlet fever ensured he did not die on the death marches from Auschwitz that preceded its liberation. Levi went back to Turin, to his job in a paint factory, and began writing, creating books that have haunted his readers because of his refusal to flinch from the evidence.

As a chemist, Levi was always fascinated by how nature works. He had, we were told, ‘a deep need within to understand what underlies nature’. You can’t lie with nature, you have to be straight with it. And, as he begins writing about his experiences in the war, he comes to realise he can’t excuse but neither can he judge what happened. He does not seek to understand; merely to witness. This is how it is.

Which is why the ‘dramatisation’ of the book on Radio 4 was such a disappointment. As a collection of stories each based on a different chemical element, you might suppose there was no connecting thought running through The Periodic Table. But the effect on reading is a slow accretion of understanding as through each element Levi exposes a different aspect of what it is to be human. Each story builds on the last by adding something more to the bigger questions that he is challenging about the war, Nazism, our ability not to see what is in front of us. Unravel that order and the deeper truths within the book are lost.

The series began with almost the last story, ‘Vanadium’, which tells of an extraordinary coincidence. In the course of his work, in the 1960s, Levi came across a name, Doktor Muller, which reminded him of the boss of the lab he had worked in while at Auschwitz. Could this be the same person? At first such an idea seemed ludicrous but Levi, with his forensic memory of all that happened to him in the war, identifies that it is the same man and sends him a copy of his coruscating book of witness, If This Is a Man. That first episode ended with him waiting for a reply.

By giving us this story first the dramatisation unbalanced the meaning behind Levi’s book. You might think he was a Nazi hunter, always obsessed with tracking down those who had tormented him. We were given no sense of his fascination with chemistry and the natural world, which is, after all, the starting point for the book. Added to this, the story was also ended too soon, cutting off Levi’s voice. Doktor Muller does reappear in a later episode near the end of the series, but the disruption of pace and meaning for dramatic effect is unforgivable.

Saturday-night’s 45-minute The Moral Maze on Radio 4 passed in a flash, which was not perhaps as intended. This week Michael Buerk’s team of panellists and witnesses were discussing the tricky question of giving and taking offence, inspired by the howl that went up after Andrea Leadsom’s comments about motherhood and childlessness. ‘When does personal opinion become morally unacceptable?’ asked Buerk.

The debate that followed, between Matthew Taylor, Giles Fraser, Claire Fox, Anne McElvoy and their witnesses, an academic, a political commentator, a comedian, and Peter Tatchell (strictly two men, two women) took us into identity politics, patterns of privilege and intentionality. The time passed quickly because the witnesses were without exception articulate, thoughtful, wrestling themselves with the question of how we should police offensive talk, and who decides what is offensive, in what context. But by the end there was frustratingly little to engage with or conclude. It was as if they were skating across the plains of meaning. No solutions were suggested to the problems raised by conviction on one side and outraged feeling on the other, or to the need to protect the freedoms of public debate.

They sing it in Islamabad, Oslo, Jakarta, Ghana and Johannesburg. It has a universal message of hope. And it was born in the slave plantations of North America. Gospel is now big in all corners of the world, as Rita Ray illustrated in this week’s Global Beats (Sunday) on the World Service. Listen out for Marriam and Sana Maqsood, sisters in Pakistan and part of the very small Christian minority, who ‘sing songs for God’ in a weird but rather wonderful blend of Bollywood and Christian pop. Or the massed voices of the Oslo Gospel Choir, the biggest-selling act in Norway, whose conductor says, ‘We’ve not grown up in the black church. We don’t try to copy it. We just try to put ourselves into it.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in