It is at the Coliseum that I have seen the most wonderful Tristan and Isoldes of my life, both of them under Reginald Goodall, in 1981 and, even more inspired, in 1985. Neither was particularly well produced, but nothing stood in the way of the musical realisation, as complete as I can ever imagine its being. After last year’s quite glorious Mastersingers, I had the highest hopes of Edward Gardner’s conducting of this new production, but they were dashed — in the case of the music, not drastically; but the idiocy of the costumes and the production is so gross that no performance could survive it.

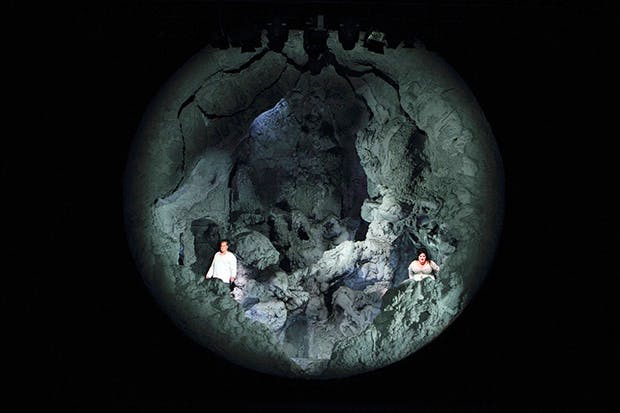

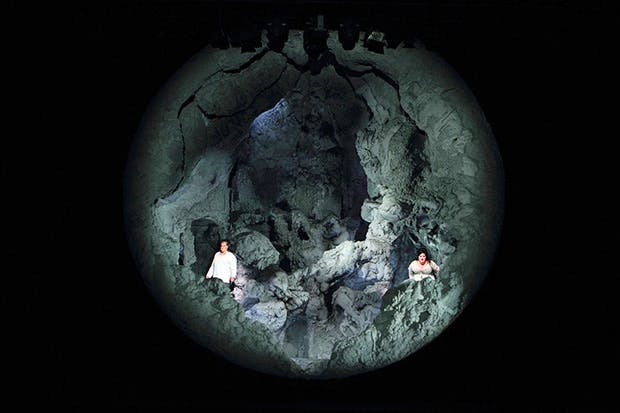

The settings are fashionably by Anish Kapoor, but though they aren’t repulsive they do nothing to help our understanding of the drama. Act I has a tripartite set, with the central section used only at the end when King Marke’s courtiers, then the King himself, briefly appear. Act II seems to take place in a volcano, of which we are given a bird’s-eye view. Act III has a gaping wound in a white wall, over which Tristan’s blood spreads — that is rather impressive.

The costume designer Christina Cunningham, no doubt working in league with the producer, Daniel Kramer, manages to sabotage what impressiveness the sets have. The two central figures are at first innocuously dressed, but Brangäne and Kurwenal are kitted out as performers in a Restoration farce, and mince around, Kurwenal spraying Tristan with scent before he confronts Isolde. I’ve seen many perverted productions of Tristan, but this is the first one in which camp figured. Meanwhile Isolde has been put into a vast hooped dress — all this in case one has ignored the words, which make the nature of her enraging arranged marriage perfectly clear.

Kramer’s ideas are not only distracting and irrelevant, they are infantile and silly. In Act II the lovers go in for self-harming during the duet, as they clamber to no purpose over the innards of the volcano, and when they are interrupted at their climax it is not by huntsmen but by a large medical team, who wheel on beds and force the lovers on to them before strapping them down and sedating them. Into this nonsense strides the immensely imposing King Marke of Matthew Rose, who sings his long monologue here, and his shorter contributions in the last act, with a nobility and richness of tone that makes it obligatory to see this production, as nothing else does. He is clothed traditionally, and sings his lament straight out to the audience, a representative, presumably, of a faded era.

Isolde is taken by Heidi Melton, the possessor of a lovely voice, but not vocally convincing as Isolde, because, while she narrated and cursed superbly in Act I, she couldn’t do much more than hold her own in Act II, lacking the sumptuousness needed for the invocation to Frau Minne; and her so-miscalled Liebestod was touch and go. In one of his most outrageous interventions Kramer had Tristan resurrected while Isolde sang, ignoring the crucial point that the whole pathos, as opposed to the ecstasy, of the last 20 minutes of the drama is that the lovers die apart, and deluded. It must be torture to be almost but not quite able to sing this role of all soprano roles, but I’m afraid that Melton is in that position.

By contrast, Stuart Skelton seems to have what it takes to get through his role — by the way, the heinous 12-minute cut in the Act II duet, which I had hoped had disappeared for ever, was imposed here; in what other opera is there a comparable act of barbarism, still? Skelton looks good, acts reasonably well, especially hard in this production, and stays the course with voice to spare. All he needs to do now is to deepen his grasp of the words: there is no inwardness in his singing. Last year at Longborough, Peter Wedd, admittedly in a theatre one fifth of the size, was far more moving. Skelton’s invitation to Isolde to accompany him to ‘the wonder-realm of night’ didn’t move me at all, nor his rantings in Act III, the profoundest part of the work.

More obviously than in any other opera, the most important man is in the pit. After a shattering Prelude, stupendously played, Gardner seemed to be feeling his way, often eliciting excessively quiet playing, but more worryingly letting the tension slip from the music. That happened in each act, but acutely in Act III, where Wagner’s masterly transitions threatened to become stagnations.

But there were many things that were beautiful and exciting, and I can well believe that in later performances the musical aspect will be much stronger. The appalling production will, as they do, survive in all its lethal perversity.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in