Isabelle Huppert does nothing by halves. And she doesn’t, I think, care greatly for journalists. She expects them to ask stupid questions. Sitting before me in an airless room in the eaves of Paris’s Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe, she is tiny, dressed entirely in black and more or less unsmiling.

Lily-skinned, red-haired, and with a fabulous curl in her upper lip, she’s appeared in more than 100 film and TV productions. Ninety minutes after our meeting, she will be on stage. I sense she wants this interview over fast. But at the start she makes me, I must report, comatose with wonder. I have adored Mme Huppert on screen for three decades, in which she seems to have had barely a month off work. I am, pathetically, spellbound.

She trained in theatre and has never abandoned it. Twenty years ago she was Mary Queen of Scots in Howard Davies’s National Theatre staging of Schiller’s Mary Stuart, opposite Anna Massey’s Elizabeth I. In 2002, she was the solo, and very still, protagonist in an internationally touring French version of Sarah Kane’s 4.48 Psychosis, directed by a then 79-year-old Claude Régy.

She opens Polish director Krzysztof Warlikowski’s Phaedra(s), which comes to the Barbican on 9 June, with a soliloquy by Aphrodite. The text at this point is by the Lebanese-Canadian Wajdi Mouawad (one of three writers credited). In it she announces that civilisation, ‘this nobility, this culture …these laws, and this freedom of speech and to be who you want …have sprung from my cunt’.

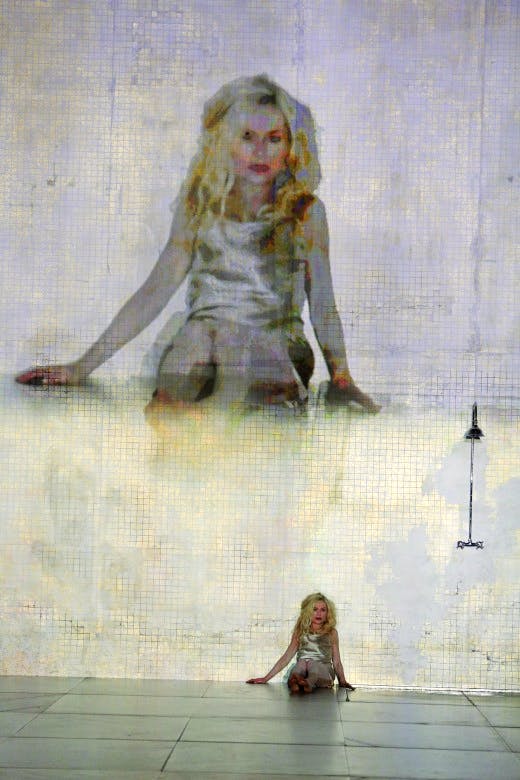

Then, as Phaedra, Huppert crawls around the stage, thighs apart, menstrually blooded, depicting a woman in deathly crisis. Soon after she vomits into a basin. The object of her love, a young man who is also her stepson — Hippolytus, drawn from Euripides’ drama of 428 BC — and for whom she should not therefore be expressing any desire, turns into a growling, prowling dog.

Not long after that section of the play, Phaedra performs oral sex on Hippolytus, a spoilt, unpleasant ‘prince’ reimagined 20 years ago from Euripides’ same Greek myth by none other than Sarah Kane (who committed suicide in 1999). This Hippolytus has already kicked off his part in Phaedra(s) by wanking into a sock. Later, a priest fellates the prince. These are Kane’s stage directions.

Worshippers of nuanced screen goddesses everywhere — and anyone who might believe the Phaedra story to be a sombre, even repressed one on stage — you have been warned: this is the most sexually unhinged piece of French drama to hit London in years. At the same time it feels a little top-heavy with verbiage; and Kane’s second full-length play, Phaedra’s Love, was arguably her weakest. Phaedra(s)’s final section, based on a 2003 essay-fiction by J.M. Coetzee, presents us with a smart, bespectacled intellectual, Elizabeth Costello, in conversation with a TV anchor about the gods, eroticism and women’s power: urbane realism strangely bolted on to two hours of tortured expressionism. Warlikowski’s approach to form seems a touch uneven.

Still, Huppert’s commitment to his project is total. Her performances through three renderings of the love-crippled Phaedra are extraordinary. There is even some Racine right at the end. Moving from character to character, from screaming terror to artfully delivered narrative as the media-savvy scholar Costello, she unleashes an astonishing tour de force. Over three hours-plus Huppert, now 63, fills the stage with the vigour of a 30-year-old. She is riveting.

Isabelle Huppert in Warlikowski’s Phaedra(s)

Huppert has worked with the Pole once before. How, I ask in French, did the collaboration come about? ‘We met when he was doing The Dybbuk in 2004, which I really liked. We then did A Streetcar Named Desire together. He asked me to work with him on this Phaedra idea…’

This is where the interview nearly comes unstuck. I’m not listening to the answer but staring at her red hair. I seem to ask the same question again. Huppert suggests, tartly but quite fairly, that we continue in English. Oh God. Abject bluster, and a deep blush, follow: I get the conversation back on track, in her own tongue. Did she contribute to the words? ‘No. When we began, there was nothing. I knew there’d be Kane and Coetzee, and only that Mouawad would, with Krzysztof, be working with the mythological figure of Phaedra, basing the text on Euripides and Seneca.’

How disconcerting is it to play a woman who wants to sleep with her stepson? ‘These texts address universal and fundamental themes: desire, fear of death, guilt. I didn’t feel a need to go after any historical truths in my research. Mouawad presents us with a somewhat geopolitical Phaedra — an émigrée, a princess from a family destroyed by Theseus. She marries an assassin, and thus feels a double guilt. Yes, Hippolytus is her stepson, but also the son of the man who killed her family. It’s true. It’s morbid!’

And Jean Racine — has she played the 17th-century master’s version of the enflamed stepmother? ‘Never. Of course I know the Racine, and I have some beautiful lines of his to recite, as Elizabeth Costello, at the end. But what became very clear was that Krzysztof wanted to recompose the character from the ancient writers through completely new writing. And the way in which I play Sarah Kane’s Phaedra is of course highly influenced by the fact that I have acted Kane before. Her language is really that of the unconscious, something in some senses also quite abstract.’

How does she keep the energy levels of Phaedra(s) going? ‘Theatre is always hard. This piece, which is really three plays, requires a particular effort, though it’s actually not as hard as it might look. At the start it was difficult to retain the texts and find any continuity, but now that I know the whole thing by heart it’s very exciting to do it each night. I take huge pleasure in its variety.’

She loves theatre’s freedom, though stresses that for her there are no great distinctions between what she does on a stage and in front of a camera. Huppert is part of France’s cinematic DNA. Many of her films are modern classics. They include Claude Goretta’s The Lacemaker (1977), Maurice Pialat’s Loulou (1980), with Gérard Depardieu — an actor with whom she has shared several screen romps (from 1974’s Les Valseuses to 2015’s Valley of Love) — and, as an ex-nun writing porn, Hal Hartley’s Amateur (1992).

In her trailblazing years, she excelled at extremes. As a relatively unknown 27-year-old, she was a brothel-keeper in one of the most financially disastrous films of all time, Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate. In 2001, she was the damaged Erika Kohut in Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher, in which her character is driven to snip her genitals with a razor blade.

‘It’s quite simple working with Michael. You have a sense of what he does being complicated but actually, when you get down to it …He’s someone with a very precise vision of what he wants, which he obsesses over. He creates a very strong atmosphere before he starts: he wants everything, the tiniest detail, to be pre-prepared.’

In her latest part, in Paul Verhoeven’s Elle, which has just premièred at Cannes, she stalks her rapist. She’s played some more traditional roles too, including Emma Bovary for Claude Chabrol, a director with whom she’s had many fruitful collaborations since the late 1970s.

Her work with Warlikowski has kept her away from the camera for at least two or three months, but she’s back with Haneke in July, on a film called Happy Ending. She has, she says as we finish talking, one golden rule: ‘In theatre or film I work only with directors I like.’

It’s hard to imagine that her screen work will ever dry up. On the evidence of Phaedra(s), stage directors will be queuing up outside her door for years to come.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in