At one time, Damien Hirst was fond of remarking that art should deal with the Gauguin questions. Namely, ‘Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?’ Hirst would sum up with a deft shift from post-impressionism to Michael Caine: ‘What’s it all about, Alfie?’ The new exhibition of work by the American artist Jeff Koons at Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery might raise the same query in a visitor’s mind.

Among other sights, you are confronted by a number of brand-new vacuum cleaners, mounted over neon lighting tubes; soon afterwards by a shiny blue sculpture, six metres high, representing a monkey made out of twisted balloons. Then there are two highly explicit images of marital relations between Koons and his ex-wife, the Italian-Hungarian porn star and politician La Cicciolina. Another sculpture, just under 4 metres high, skilfully mimics a mound of multicoloured Play-Doh. So, what is all this about?

There is an answer. Indeed, there are at least two. The enemies of Koons would say that all this is a nihilistic recycling of glossy, mass-market junk. The black irony, they would add, is that Koons is among the world’s most expensive artists: a case of grotesque wealth pursuing utter vacuity. On this analysis, as Jonathan Jones put it in the Guardian, Koons is ‘the Donald Trump of art’.

Koons himself, on the other hand, would say that his art is all about ‘transcendence’ and ‘fertility’ (he has a tendency to talk a bit like a self-help manual). First, he told me a few years ago, one has to accept one’s own body and overcome ‘one’s cultural guilt and shame’, then one can ‘expand one’s parameters’. His other theme is what biologists call reproduction. ‘Basically I believe in life,’ he announced, in Walt Whitman mode. ‘I embrace sex and sexuality.’

There is certainly a lot of the last in the show, and it is not confined to the items co-starring the first Mrs Koons. On closer examination, his imagery generally seems to refer to penetration, orifices and piping. That applies to those vacuum cleaners with their dangling hoses, for example. But there is nothing the matter with an artist having a one-track mind. It can be a positive advantage, concentrating the work (there is a good deal of repetition, fertility and sexuality in Rubens, for example).

My quarrel with Koons is that he is extremely erratic. Admittedly, this is a haphazard exhibition, vaguely entitled Now but with an emphasis on early pieces — such as extremely dull photographs of people holding basketballs. But on this basis, Koons only occasionally gets it right.

Thirty years on, the vacuum cleaners look very slight. His paintings, such as ‘Girl with Dolphin and Monkey’ (2009), executed in a slick photorealist mode by platoons of assistants, are too much of a muchness for me. They consist of layers of cheerfully libidinous imagery — in this case, tumescent inflatable toys, a speeding train and a young woman in underwear — all in a jarring lime-green and mauve colour register.

The big sculptures, however, can have memorable oomph and energy. Take ‘Balloon Monkey (Blue)’, 2013. It’s huge, curvaceously baroque and when you look into its surfaces you see yourself and everything else around reflected, just as the whole universe seems mirrored in Monet’s lily ponds. On the other hand, it’s a silly toy.

Perhaps Koons is suggesting that we have to accept the trivial banality of our culture before we can understand it, and ourselves. That’s gall and wormwood to an old-fashioned art-world elitist — the whole basis of avant-garde culture used to be that it is quite distinct from mass-market kitsch — but it’s quite a radical thought.

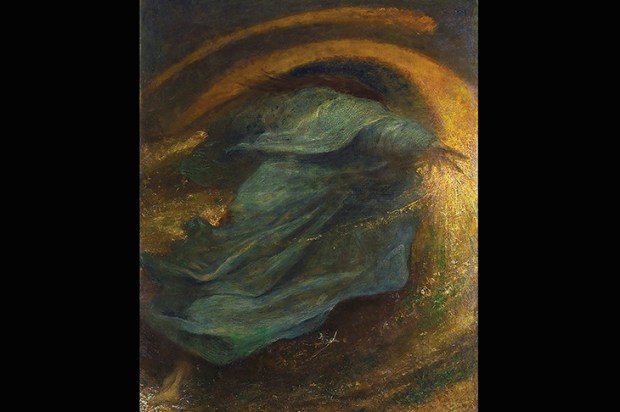

There’s less discomfort for antiquated aesthetes in Quick Light, an exhibition of work by the veteran New York painter Alex Katz at the Serpentine. However, it’s not straightforward viewing either. Born in 1927, Katz is a maverick from a now-distant generation. He began painting in the 1950s — the high noon of abstract expressionism when the influences of Pollock and Rothko were at their most powerful.

Katz, however, felt an urge to depict the real world. He has been doing so ever since, but in an idiom that owes a lot to abstraction. His paintings have strong colours, simple forms and a self-invented style of drawing that — at first glance, at any rate — can look a little naive. Their grand scale and clarity are very American.

The trouble is that Katz’s subjects — women’s faces, rippling water, woodland, snowy landscapes, twinkling lights by night — are, if anything, too soothing, too lovely. Oddly, his pictures can remind you of one of Koons’s titles, ‘Easyfun-Ethereal’. But perhaps it’s best not to fret too much about those Alfie questions: after all, Gauguin didn’t really have much of an answer to them either.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in