‘So you’re going to see the gay sex opera?’ exclaimed my friend, open-mouthed. People certainly seem to have had some odd preconceptions about Mark Simpson’s new chamber opera Pleasure. The distinguished critic of the Daily Telegraph let it be known that he awaited ‘with trepidation, something set in the lavatories of a gay nightclub’. And to be fair, the news that Pleasure was to star Lesley Garrett — last seen in Welsh National Opera’s Chorus! ascending to the heavens aboard an enormous pair of lips — didn’t exactly dampen suspicions that we were about to see some sort of camp spectacular: Adès’s Powder Her Face meets RuPaul’s Drag Race.

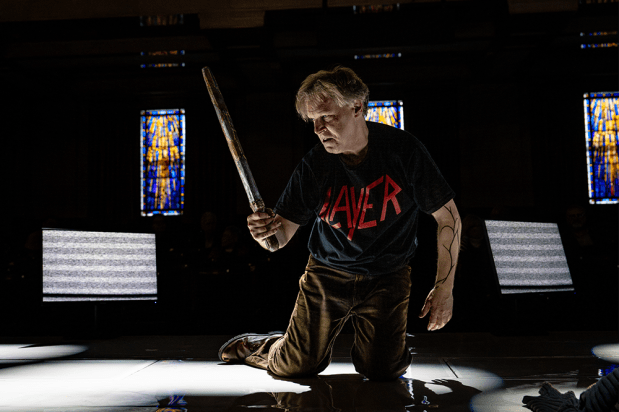

In fact, Pleasure is about as non-camp as any opera can be that features a six-foot man delivering an aria clad only in stiletto heels, make-up and balloons. Leslie Travers’s set comprises the neon-lit letters of the show’s name. An overflowing wheelie bin and a lavatory basin lurk behind them, plus a box of teabags (Yorkshire Tea, naturally) — reminders of bleak realities and small comforts. Within this single setting and a running time of little more than an hour, Simpson unfolds a tragedy that had audience members around me in tears. That’s a tribute to Simpson’s score: a dark, glistening thing that pulses with minimalist rhythms and heaves itself up into grand baroque gestures while letting vocal lines rise naturally and push through the texture. Tim Albery’s direction draws affecting and realistic performances from the central couple, Timothy Nelson and Nick Pritchard: a remarkably tender portrayal of love frustrated by class as much as by Steven Page’s malevolent drag queen (the main prejudice explored in Pleasure is between generations).

But it’s also a tribute to Garrett’s astonishing, late-career-defining portrayal of the lavatory attendant Val. She wears faded jeans and a grey cardigan, hair tied aggressively back; and the voice isn’t particularly glamorous either. But it’s focused, and fierce with emotion: appropriate to the character, and wholly compelling. Val’s two careworn monologues open and close the opera, and will probably be the reason why Pleasure enters the repertoire, if it does. If it doesn’t, Melanie Challenger’s libretto will have something to answer for. Using Important Poets as opera librettists is a habit that British composers seem unable to shake, and the results are usually terrible, at least when an opera aspires to some kind of contemporary realism. ‘Their words of fear spread over me like sunlight in a garden’: does anyone talk like that in a Leeds nightclub? Or anywhere? It just makes the whole thing seem (the old libel) exotic and irrational.

Iain Bell’s In Parenthesis tackles that problem head on. Not that you’ve much choice when your source material is David Jones’s first world war epic. Jones is the hipster’s war poet, beloved of those for whom Owen, Sassoon et al. are just a bit too GCSE English (‘I’m into war poetry you’ve probably never heard of’). In Parenthesis is a multilayered thicket of fractured modernist language and Celtic and Catholic myth, with a verbal music that should really be a warning light to any composer, let alone a librettist.

Incredibly, it works. Neither director David Pountney nor librettists David Antrobus and Emma Jenkins attempt to hide the artifice. Bards of Britannia (Peter Coleman-Wright) and Germania (Alexandra Deshorties) act as narrators and presiding spirits; the female chorus acts as, well, a Chorus, and the narrative moves fluidly between earthy realism and high-flown mythic commentary. Antrobus and Jenkins have somehow managed to separate out a clear storyline while keeping Jones’s most potent images: the cheese ‘clammy, pitted with earth’, the ‘silky rodents’, and of course the whole complex of Arthurian and Christian symbolism. The very artificiality makes that plausible, even as Coleman-Wright and Deshorties don Wagnerian armour, the women of the chorus start walking about with shrubs on their heads and the whole thing teeters on the brink of Monty Python.

That the production comes through is down to the passionate conviction of the performances — notably Andrew Bidlack and Marcus Farnsworth as a pair of Tommies, and George Humphreys as their Christ-like young commander — the beauty and inventiveness of Robert Innes Hopkins’s designs, with their shifting back-projected cloudscape, and the symphonic power of Bell’s score, conducted by Carlo Rizzi with the sort of majesty and lyricism he brings to Otello. Bell’s a composer who isn’t afraid to open an act with a chorus of ‘Sosban Fach’, or to portray the flight and impact of an artillery shell with a bit of good old-fashioned Richard Strauss-style tone painting. Vaughan Williams and Wagner surface from time to time, too, before the tide sweeps grimly onwards towards the Somme. If In Parenthesis doesn’t spend enough time with any one character to make them come entirely alive — and if there’s something distinctly queasy about watching the agonised death of a young soldier serve as the prelude to a prettified final redemption — it certainly felt like everyone meant it. A packed Wales Millennium Centre cheered and cheered.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in