Comic opera is no laughing matter. Seriously, when was the last time you laughed out loud in the opera house? The vocal slapstick of Gianni Schicchi, laid on six banana skins deep? The farcical plot convulsions of Il barbiere? What about the arrival of Mozart’s ‘Albanians’ in Così? (Oh, those moustaches! Oh, those naughty boys!) It’s all about as spontaneous as a health-and-safety briefing, and almost as funny. Thank goodness, then, for Gerald Barry’s The Importance of Being Earnest — an opera that’s dangerously, anarchically hilarious.

The project sounds like a joke in itself. Have you heard the one about the Irish composer who tried to improve on Oscar Wilde? But the punchline (and it’s a punch that lands square in the face) is that Barry actually succeeds, taking a highly polished comedy of manners and turning its toothpick barbs into blades, wielding them not only at the social pretensions and conventions of the drawing-room, but also at contemporary opera and opera-goers themselves.

It all starts with Barry’s libretto. Cut and pasted directly from Wilde, it’s then cut again. And again. The result is so fragmented, so fractured and disjointed, that words are wrenched free of their meanings, reduced to percussive syllables that hammer relentlessly at the ear. Wit is no longer a verbal concept but a sonic one. Some of Wilde’s aphorisms remain, but many more are traded for sardonic orchestral interjections (the orchestra has strong feelings about much of the onstage action) and musical jokes that range from the slapstick (the 50 smashed plates that puncture and punctuate the surface politeness of Cecily and Gwendolen’s first meeting, the brass bumblebees that so persistently interrupt Miss Prism’s afternoon in the garden) to the subtler mockery of avant-garde musical textures and effects.

Characterisation is woven so tightly and completely into Barry’s vocal writing that half of the singers’ work is already done. Drawing-room dictator Lady Bracknell is cast as a bass (unequivocally masculine, no simpering pantomime dames here). Cecily’s vapid innocence manifests in stratospherically high writing — beautiful, impractical — while Miss Prism’s repressed romantic yearnings inhabit the lower extremes of her register, occasionally leavened by moments of querulous expostulation at the top. Everyone sounds uncomfortable most of the time, pulling the vocal rug from under the glamour of the operatic voice.

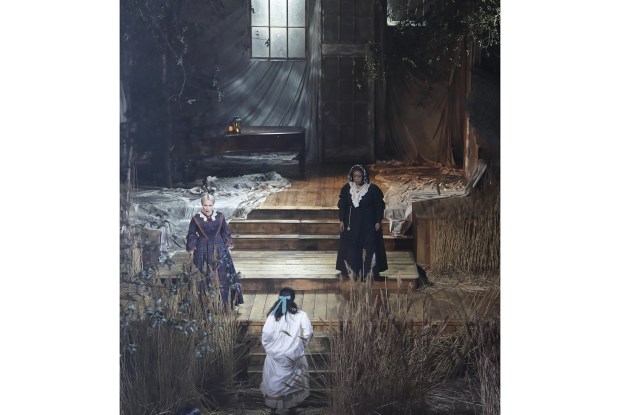

Ramin Gray’s 2013 production for the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Theatre returns, upgraded to the rather more spacious Barbican Theatre. It brings with it most of its superb original cast, but also the same dramatic flaws that chafed first time round. Gray places his orchestra (here the dynamic Britten Sinfonia) on a stage consisting solely of a set of steep steps. Everyone totters up and down, failing to find a foothold in Barry’s anarchic action, but, metaphors aside, it all looks rather non-committal — a semi-staging by any other name. Contemporary clothes, onstage props tables and costume racks might seek to subvert the formality of Wilde’s proscenium-framed play, but instead they just add clutter to a score already stuffed to bursting with ideas.

The dream cast do Barry proud, though. Claudia Boyle (the only new principal) is pouting perfection as Cecily, diaphanous of tone and mind, doing battle over the afternoon muffins with Stephanie Marshall’s forthright Gwendolen, by turns prim and sexually rapacious. Jack and Algernon (Paul Curievici and Benedict Nelson) spar deliciously, the steel of Curievici’s tightly wound tenor set against the bonhomous meanderings of Nelson’s cushioning baritone. The laurels for operatic Grande Dame of the evening are torn in a tug-of-war between Alan Ewing’s stentorian Lady Bracknell and Hilary Summers’s Miss Prism, all wounded eyes and warrior-like contralto. All are supported by the Britten Sinfonia, who stamp, speak and sing as well as play their instruments, bringing verve and clarity to the block textures of Barry’s score under the direction of Tim Murray.

The current run is The Importance of Being Earnest’s third appearance in London since its 2012 première. Pretty good going for a contemporary opera, and a sure sign that this is a piece that’s here to stay. But how criminally, wilfully wasteful that this extrovert gem of a work still hasn’t had a mainstage outing at any UK house. Given the amount of operatic tosh that has (Miss Fortune, anyone?) and the sell-out crowds at the Barbican, I hope that there’s an artistic director or two feeling pretty foolish for failing to bet on the surest hit the opera house has seen this decade.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in