Near the end of Elena Langer’s new opera Figaro Gets a Divorce, as the Almaviva household — now emigrés in an unnamed 1930s police state — prepares to flee, the Countess announces that she intends to leave her trunk behind. It’s not the subtlest moment in David Pountney’s libretto. Any opera that sets itself up as a sequel to The Marriage of Figaro is already courting comparisons that are both completely unavoidable and massively unfair. When the production of Figaro is as good as this one, that baggage can become so heavy that it’s immovable.

Welsh National Opera isn’t the first company to present The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro as a pair, and Langer’s isn’t the first attempt to create a third drama using Beaumarchais’s characters. Pountney’s libretto is based on a play by Horváth, itself an updating of Beaumarchais’s own rather unsatisfactory La Mère coupable. Then there’s Massenet’s Chérubin, which borrows a single character and whips up a soufflé around him. On balance, that’s the safest approach — creating a wholly new and self-contained world each time.

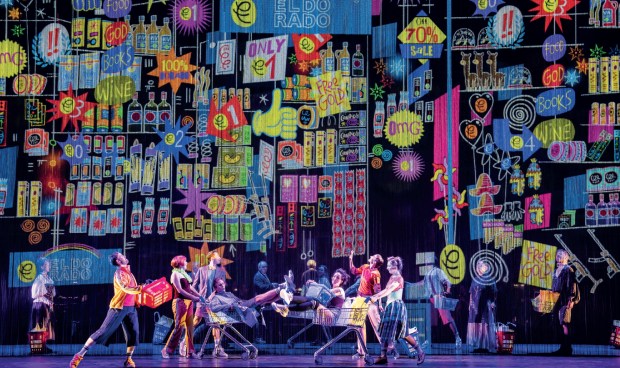

And that’s where WNO’s new Marriage of Figaro succeeds. David Stout’s Figaro bustles in through the audience mid-overture, a touch of pantomime that sets the tone. It’s no bad thing to be reminded that Figaro is a comedy, and throughout the evening, director Tobias Richter gently nudges it over the line. Figaro himself is cheerfully theatrical, all raised eyebrows and flourishing hand gestures. Surreal touches — an exploding iron, a flickering lightbulb — fit well with the big, abstract flats of Ralph Koltai’s set. Characters address the audience directly (Susan Bickley’s Marcellina sipping a glass of champagne as she does so) and Sue Blane’s bright period-appropriate costumes are just cartoonish enough to wink at the artifice without puncturing it.

Best of all though, with Lothar Koenigs conducting, it absolutely fizzes. The jokes land, and the principals (many of them WNO regulars) play off each other marvellously. Stout’s dark, flexible voice makes an effective foil for the paler tones of Mark Stone’s Count and Elizabeth Watts sings with a richness and sense of shade that nicely complements her more than usually impulsive portrayal of the Countess. If the Count and Countess’s final reconciliation didn’t quite pierce the heart on this first night, the essentials are in place: it’s the sort of thing that might well blossom naturally as the run continues.

Meanwhile, there’s a Cherubino (Naomi O’Connell) who actually acts and sounds like a hormonally challenged teenage boy, and a minxy Barbarina (Rhian Lois) who’d happily eat the Count alive, let alone his page. And, above all, there’s Anna Devin as the Susanna of your dreams: smart, funny, with emotions flashing across her face by the microsecond and a sunny, crystal-clear voice that can hang blissfully in the air or — in Act Four — make Mozart sound as lusciously lubricious as Richard Strauss. Lucky Figaro. Lucky us.

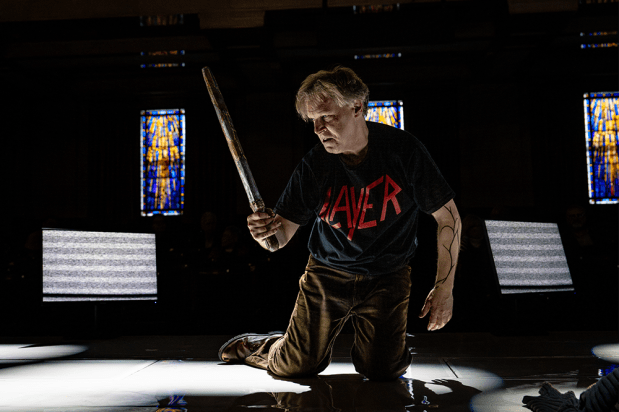

The Almavivas’ luck is running out in Figaro Gets a Divorce. In La Mère coupable, written in 1791, Beaumarchais is clearly uneasy with the implications of relocating his beloved characters to revolutionary France, and in updating the story to 1930s Mitteleuropa, Pountney has taken that unease and run with it. Here Koltai’s sets come into their own, suggesting pre-war monochrome illustrations and swinging round to become back alleys or seedy apartments.

Opera buffs will enjoy the various flavours of Langer’s score: a splash of raw Janacek, a sprinkling of Rosenkavalier sweetness, and big, throat-burning glugs of Kurt Weill. But it also has a lyricism and a satin-stringed, vibraphone-shimmering sheen that evokes Hollywood-era Korngold: a fitting sound for what’s essentially an operatic film noir, and under Justin Brown the WNO orchestra sounded as though they were enjoying it. Pountney’s libretto mostly avoids Pseuds Corner (though the last line is horribly arch), and as director, he moves things along briskly.

That’s the problem. With so many ideas to address (Cherubino, for instance, is now a club owner and drag queen, sung by countertenor Andrew Watts) it feels sketchy. At least one crucial bit of exposition is set, inaudibly, as an ensemble, and vital details — the plot turns on the precise relationship of the two youngest characters, Angelika and Serafin (sung by the previous night’s Barbarina and Cherubino) — aren’t clearly spelled out. Most of the cast are carried over from Figaro (Marie Arnet takes Devin’s place as an altogether steelier Susanna), but on first hearing, Langer’s music doesn’t quite have time or space to bring all these characters to life, the notable exception being the harsh, angular tenor of Alan Oke’s malign secret policeman, the Major. We’re simply expected to have read the programme — and to have seen Figaro recently. Figaro Gets a Divorce has a story to tell, and a lot of atmosphere. But it can’t quite shed that baggage.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in