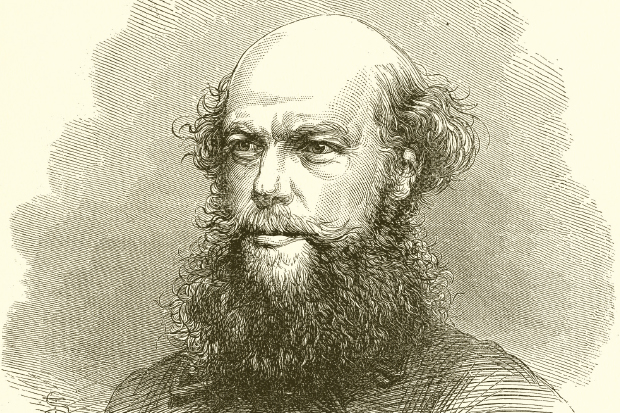

As an erstwhile obituarist, I pity the poor hack who had to write up the life of Laurence Oliphant — adventurer, diplomat, war correspondent, mystic, spy (and the subject of Bart Casey’s biography) — when he died, aged 59, in 1888. The first paragraph should (according to the well-seasoned formula) contain some characterising incident or achievement, giving the measure of the man, the impact he made on the world and those around him, and an indication of his interior life.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £17.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in